The Success Code is now available to read in all of its Amazon Kindle glory! 😀Pick up a copy and after you have a chance to read, let me know…

Become A Full-Time Writer

The Success Code is now available to read in all of its Amazon Kindle glory! 😀Pick up a copy and after you have a chance to read, let me know…

When you first set out to become a freelance writer, you charge whatever you think is “normal.”

In the process of determining that rate, you consider the pay scale of jobs you’ve worked in the past, consult industry pricing sheets, and read every “How much should I charge?” resource you can get your hands on.

And after reading all of those blogs and getting pep talks from the best writers out there… you still turn around and charge $15 or $20 an hour for all kinds of writing services.

I know why you do it. I was there. I started my writing business charging $35 an hour and I felt pretty darn lucky to get the business that came in (and, truth be told, I was indeed lucky to get it because I was just getting started).

Because no matter how many articles I read telling me to charge more, I never quite understood why I should charge more, or how I should go about it.

Well, new writers, your day has come! Here’s a look at the real consequences of charging $20 an hour to write and how to make the switch to a more profitable rate you deserve.

The truth of the matter is that a minimum writing rate is however low you’ll go when you need money.

It’s important to know that number for business purposes, but using that number to guide your pricing is a huge mistake. It points the nose of your plane at the ground and limits your ability to earn from the get-go.

For some, it’s thrilling to surpass the minimum wage at $15 per hour, and it beats unemployment. Many others, including myself, realize after a few months that charging this low rate is not the equivalent of a full-time writing job, and is simply not sustainable.

Beyond the threat of going out of business because you aren’t making enough, charging too little makes freelancing stressful and hard. It makes you work overtime, and on projects (and with people) who don’t feed your love of writing.

If you love freelancing and you are getting great feedback from your clients, the time has come to raise your rate. But trust me, if you go from $20 to $100 an hour, you’ll lose all your clients.

So how do you do it without alienating the people you want to work with?

Here’s the rub: Raising your prices when you work hourly is extremely difficult. Going from $20 an hour to $50 an hour will feel like an unwarranted hike for your clients and you’ll feel the need to justify every dollar of that increase.

And worse yet? It still won’t help you achieve the freedom you want to achieve. Even charging $100 per hour (which few clients will pay for writing) won’t disengage you from the need to be active in your business 40 hours per week, because of all the unpaid time spent invoicing, marketing, paying taxes, and hunting down new work.

All hourly pricing turns your time into a commodity. Instead, you need to shift to the most profitable way of charging for you and the most convenient form of billing for your clients: Project or value-based pricing.

When switching your current clients from a low hourly rate to an equivalent project rate, you don’t have to make it a huge deal.

Simply translate how much you’re billing your client hourly right now and match it with the tasks you’re performing. Then round up to get a “project rate” for the assignment.

For example, let’s say you’ve been writing four blog posts for a company at $20 an hour and you’ve been invoicing four-to-six hours each month for the past few months for a total invoice of $120. Simply take the six-hour rate ($120) and turn it into a per-post rate of $40 for each of the four posts.

Boom, you have a project rate.

Here’s a simple email template you can use to switch your clients to a project rate in that scenario:

Hello Client,

Thank you so much for paying [most recent invoice]! I really enjoyed working on this project, and I can’t wait to get started on [next assignment].

Regarding my future invoicing, I am shifting my business to a project rate model. This won’t affect our relationship very much — in fact, this will make it easier for you to predict your invoice each month and we won’t have to track pesky hours all the time.

Instead of charging $20 per hour, I’ve analyzed the data from our invoices the past few months and set an equivalent project rate of $40 per post. Moving forward, I’ll bill at this itemized rate so you can know exactly what you’re getting into with each new project.

Let me know if you have any questions — I’ll be happy to discuss this with you over the phone!

Sincerely,

[You]

Now that you have this project rate established, you can start implementing the secrets all high-earning freelance writers use to maximize their income: Learn to write faster (thereby increasing your hourly income) and (over time, of course) raise your project rate so you make more with each project.

You can also pitch new kinds of more valuable work (ghostwriting jobs, email copywriting, white papers, and website copywriting) at a higher project rate, thereby avoiding the discussion of hourly rates altogether as you grow your business.

One of the deepest issues writers have with charging a high rate is confidence in what you do. You naturally love to write, after all, so who are you to charge for something that comes easily to you?

I cry baloney!

Listen: Businesses make money selling ideas to their customers. Those ideas are expressed in words on their marketing material, websites, blogs, and product descriptions. Therefore, the only way any of these businesses ever makes money is…

You got it. Through the words they use.

If a business is successful or unsuccessful, it’s because it is communicating its value — with words — to clients who agree to buy. If you’re a part of that process, you’re a valuable business asset that is worth investing in — and paying more than $20 an hour.

And if you can help a business understand this process by pricing your rates according to the value you bring, they will begin to understand why investing in the best writer for the job at a market project rate is in their best interest.

Do you absolutely have to stop charging $20 per hour for your writing? Only if you want to stay in business.

Take this post as an opportunity to sit down and think through your pricing strategy so you can get on track to succeed as a freelance writer today.

What strategies have you used to determine or raise your freelance writing rates?

This is an updated version of a story that was previously published. We update our posts as often as possible to ensure they’re useful for our readers.

Photo via JKstock / Shutterstock

The post Here’s a Better Way to Set Your Freelance Writing Rates appeared first on The Write Life.

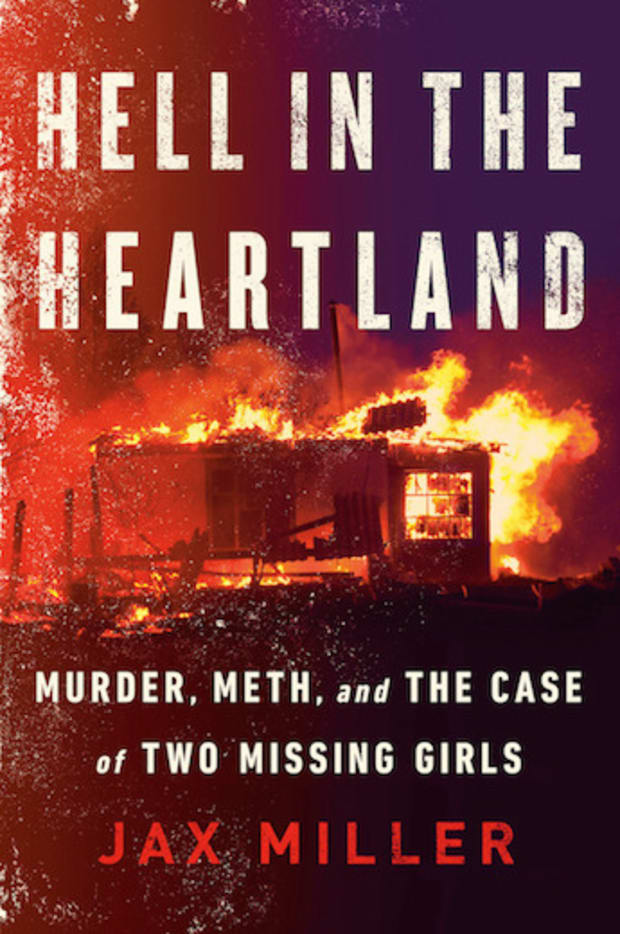

In this post, Miller shares what inspired her to switch writing genres (from fiction to true crime), move to Oklahoma, sit with convicted murderers and in meth labs, and more!

Jax Miller is an American author. While hitchhiking across America in her 20s, she wrote her first novel, Freedom’s Child, for which she won the 2016 Grand Prix des Lectrices de Elle and earned several CWA Dagger nominations. She has received acclaim from the New York Times, NPR, Entertainment Weekly, and many more.

She now works in the true crime genre, having penned her much anticipated book and acting as creator, host, and executive producer on the true crime documentary series Hell in the Heartland on CNN’s HLN network. Jax is a lover of film and music, and has a passion for rock ‘n’ roll and writing screenplays.

(21 authors share one piece of advice for writers.)

In this post, Miller shares what inspired her to switch writing genres (from fiction to true crime), move to Oklahoma, sit with convicted murderers and in meth labs, and more!

*****

Research, interview, and explore the subjects that interest you. Then write about what you’ve learned in Writing Nonfiction 101: Fundamentals. Writing nonfiction is a great way for beginner and experienced writers to break into the publishing industry.

*****

Name: Jax Miller

Literary agent: Zoe Sandler of ICM (US); Emma Finn of C+W Agency (UK)

Book title: Hell in the Heartland: Murder, Meth, and The Case of Two Missing Girls

Publisher: Berkley/PRH (USA); HarperCollins (UK)

Release date: July 28, 2020

Genre: True Crime/Nonfiction

Previous title: Freedom’s Child

Elevator pitch for the book: An author travels to rural Oklahoma to try and uncover what really happened to a murdered family and two missing teenagers.

What brought me to this story and what kept me here are two different things. At the start, I was drawn to it strictly from a storytelling point of view: It was a stranger-than-fiction story that was rich in plot and in setting (read: boundless prairies and abandoned lead-mining cities). But it was my first time writing in the true crime genre and with that came a naiveté, because once I started, I became obsessed and I had to see it through as far as I could.

(8 ways to prepare to write your nonfiction book in a month.)

Over time, I formed close relationships with the families of missing friends, Lauria Bible and Ashley Freeman and many others across Oklahoma. I had the luxury of leaving any time I wanted, but they didn’t—they still searched tirelessly for their loved ones. Once I came to really grasp that concept, I wanted to sit with them in the trenches.

The idea to switch from fiction to nonfiction came in 2014 or 2015, but after weighing out several other real-life cases, I chose the Bible-Freeman case. It haunted me for years. I was living in Ireland and I called Lorene Bible, the mother of missing child, Lauria Bible. She gave me her blessing to write the book and the rest is history. The only next logical step, therefore, was to go to Oklahoma for the first time and see what I could dig up. Now it’s become a second home.

The ideas changed constantly because the story changed constantly. I’d seen it go through different sheriffs, different agents, different suspects, so it takes a lot of mind changing and willingness to evaluate new theories that go against your previous beliefs. I’ve learned that in writing about cases that are this active, you have to be open-minded and careful not to settle on ideas.

The process with this book was longer than what I’d experienced in fiction, mostly because of how much time it took to research. I never had any intentions of writing from a desk, so I spent several years knocking on doors, conducting interviews, being away from home. That was the most-time consuming part, especially because I took on this “When in Rome” approach.

I didn’t want to bring this story to readers, I wanted to bring readers into the story, and to do that, I had to write from the heart of Oklahoma and become like one of them.

I’m thankful for the amazing team I had, because with such an active case, there were always changes that had to be made post-submission. “Hey, so-and-so’s no longer in prison.” “Can we make note of this person just passing away?” “This person decided to go on record.” I’m sure I drove them nuts at times.

Fiction and nonfiction satisfy two very different beasts in me: With fiction, there’s this beautiful escapism so that I don’t have to face reality, and with nonfiction, it’s a cold, deep plunge into someone else’s. Fiction is great if you need to escape (and I still write it often), but nonfiction is about selflessness and serving something that’s greater than yourself. That was something I didn’t realize until after I was in it.

(How I interviewed a serial killer and stayed sane.)

The work for this book required sitting with convicted murderers, sitting in meth labs, and getting into some sticky situations. So needless to say, that world was full of surprises.

It did nothing for my mental health, which I open up about in the book. But I really did finish the last chapter a changed woman. Dare I say, stronger, and much of that had to do with Mrs. Bible and her to-Hell-and-back crusade to find her daughter.

I hope readers will start a conversation: What did happen to Lauria Bible and Ashley Freeman?

On a local level, while authorities made their first arrest in 2018, there are still people with information, possibly more that need to be held accountable. Raising awareness with this story has helped garner tips and information in the past, and if this book can help in some small way, I hope it does.

March to the beat of your own drum.

I was in Jakarta for Chinese New Year.

It was February 2018. It’s funny

to say that it was colder than expected

because I still had to keep the air con on

at night and because of that and the fact

we weren’t talking then I sat up and looked

through old messages on my phone trying

to work out if there was some pattern there.

It was all about what to eat what to pick up

what to watch. The next day at the museum –

Gedung Gajah – among the empty cases

I stopped at two clay figures the caption

referred to as a married couple from

South Sulawesi. ‘A kind of toy played

by girls.’ Look at that, I said, but my

grandma was in her wheelchair downstairs

and you were in America. Both figures had

little round nipples. One hugged its knees while

the other sat cross-legged, their mouths

small and angry. They looked like children

forced to eat their soup. They made me think of

when Nietzsche saw a horse being flogged and threw

his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing

and sobbing until a neighbour took him home.

He lay in bed for two days before uttering

his final words: Mother, I am stupid.

Those two married children were talking to me.

Stupid, you’re so stupid, they said. What the fuck

are you looking at? A week later, I was in the queue

at the Peckhamplex. For three years, we’d lived

behind Rye Lane. For three years not

unhappy, very happy. Now there was

a sourdough bakery where the barbershop

had been. There were more roadworks, more

people. It was darker earlier than in

Jakarta. I was in south London and you

were in a studio in the woods in America.

That was all I knew and

filling in the blanks

only brought up blank

snow covering

the roads and more blank

snow on branches

drooping by your

window after long

days at work and on

night walks when

the snow reflecting off

your torch was the

colour of your thoughts

The wind flogged my dry cheeks as I thought

what to eat what to pick up what to watch.

I pictured my grandma’s worn mask which

in three months would be burnt and scattered on

the Java Sea. Look at that, I said, but

there was no one next to me. That night

when we went upstairs to talk, I don’t know

why or how – since you were in a studio

in the woods in America – I asked:

Who is he? You turned away. The bed was

damp. Oh we haven’t been seeing each other long.

You offered me a cigarette, though you’d

never smoked. Is that a good idea?

But already I was on your lap, sobbing

and sobbing at my own stupidity.

Photograph © MB

The post At the Peckhamplex appeared first on Granta.

Mountain, mountain, mountain.

Mountains on every side. Mountains that looked pixelated by gravel and chaparral, mountains that looked like their faces were crumbling. At certain hours of the day, with the sun disappeared and the mountains outlined, the mountain range looked like a tidal wave, about to crash down, about to sweep everything clean.

The steady desert heat meant Thora applied and reapplied medicated lip balm, refilled her water bottle from communal jugs, water tinted by lemon slices and mint. They weren’t allowed cell phones but could call home as much as they liked – after the first week, anyway. They could go into town with staff supervision. Thora didn’t leave the Center, but her roommate, Ally, came back with turquoise dreamcatchers and magazines, big Saran-Wrapped cookies from the bakery.

When Thora wasn’t in group, or doing check-ins with her counselor, she and Ally sat out by the pool in terry cloth robes, on lounge chairs that smelled a little moldy. Ally was twenty, the daughter of a senator. She wondered aloud how many Instagram followers she might have lost over the last month without her phone. Because Ally had diabetes, the staff let her keep her insulin and syringes, which she carried around in a pink zip-purse with a crown on it.

keep calm and carry on.

Thora liked to watch Ally inject herself, pooch up the pale skin above her waistband. It was almost like doing drugs herself.

All in all, it was a nice place. The landscaping was professional, attended to by many sunburned men. The food had a pre-chewed quality, lots of purees and smoothies, though, famously, the meals were good, better than at other places. Thora could attest to that, no soggy chicken fingers, no frozen chocolate cake crispy with ice shards. They were well nourished. The staff gave out vitamins in plastic organizers, grainy vitamins, probiotics in gummy form, which was another way to tell this was not quite rehab but some way station before rehab, the rules loosely enforced, the idea of authority introduced without the necessary follow-through.

It was more of a holding pen, a quiet place – it was assumed that everyone there was very tired. They were all overworked, stressed, and perhaps that had led them to make bad decisions that

had adversely affected the people around them. The Media Room was stacked with old Academy screeners, though every night for the last two weeks, Ally and Thora had watched a Ken Burns documentary about national parks. This alone seemed to take years off their lives.

When Thora called James, once a day, she could tell he was summoning a sort of gravitas, performing a solemnity he would later report to his therapist. He was attempting, she realized, to be present. Thora had only been gone two weeks: already James had started to seem theoretical, a series of still photos that didn’t quite coalesce into someone she had married.

‘You sound strong,’ James said. ‘Really.’

‘Mm,’ Thora said.

‘I love you,’ James said, somber, his voice dropping an octave.

For a moment, she studied the silence between them with curiosity: suddenly she could do things like this, stop answering, stop talking, and it was fine.

She forced herself to speak. ‘I love you, too.’ James was, she knew, not a bad person.

They were bored, lights out, Thora’s headlamp illuminating the corners of the room: the not-bad abstract paintings, the window cracked to let in the chilly night air. Outside were the dark shapes of the big aloe plants, the cacti. Thora stared at the twin beds, the matching coverlets. She hadn’t shared a room since college. It had been so long ago: she couldn’t remember if she’d actually liked any of her friends, the girl she lived with who kept her hair short, who baked loaves of sourdough in the dorm kitchen. She was a wilderness guide now. Thora was sure her life would seem appalling to the girl. Maybe it was.

Ally slept naked. Thora could’ve complained about this, she guessed – complaints were almost encouraged, showed they were setting limits and responding proactively to their environments – but she didn’t care. Thora liked the blunt fact of Ally’s presence, liked watching Ally move around, inspecting one of her pale tits for nipple hair under the lamplight. They took away Ally’s tweezers after she plucked every hair from her left armpit, though she showed Thora she could do it with her fingernails, too. She often fell asleep with one hand on her crotch, as if it was a pet. That night, Ally was reading the book she’d been reading the last two weeks. Thora had seen a lot of people carrying the book around the Center: making a big deal of bringing it to lunch, women squeezing the hardcover tightly to their chests as they walked to Restorative Yoga.

‘Can I see?’ Thora said. Ally passed it over.

Thora read just a few pages. It was about a plucky doll maker in occupied Paris during World War II. It seemed like a book for people who hated books.

‘This is terrible,’ Thora said, flipping the book to see the author photo. A woman stared back from a razzle of Aztec jewelry. ‘The author looks like the world’s most cheerful nine-year-old.’

‘It’s actually really good,’ Ally said, snatching it back. Thora had hurt her feelings.

‘Sorry,’ Thora said. Ally didn’t respond, on the edge of pouting. She had pulled the covers up over herself, turning away from Thora.

‘Wanna test my blood?’ Thora said.

At this, Ally brightened. She sat up. She had been begging to test Thora’s blood sugar.

‘Come here,’ she said, patting her bed, taking out her little pink purse. Suddenly she seemed very professional, despite her nudity.

Ally held Thora’s right hand in hers, palm up, the fingers splayed.

‘Here we go.’

She jabbed Thora’s finger, then held a tissue to it to absorb the drop of red. It stung worse than she had imagined it might. Thora sucked her fingertip hard.

‘You do this to yourself all the time?’

‘One-oh-five,’ Ally said, briskly, after feeding the paper slip into her little machine. ‘Very nice.’

Ally dropped the used needle into an empty seltzer bottle, a poky mess of trash and bloody napkins that she kept on her nightstand, like a gory snow globe.

Thora woke in the blue morning light, Ally’s voice coming from the bed next to her. ‘The people are eating,’ she muttered. ‘The people are eating.’ The medication Ally was taking seemed to make her a little crazy. When Thora went to check on her, she saw Ally was still asleep, a pillow clenched between her knees.

‘You just kept repeating yourself,’ Thora told her at breakfast. ‘Over and over.’

Ally pushed for details, asking Thora whether she’d said anything else. ‘I can handle it,’ she said, ‘just tell me,’ and it struck Thora that Ally wasn’t nervously patrolling the spill of her psyche, worried about what poisonous things she’d let slip, but that Ally genuinely hoped to learn something valuable and unknown about herself.

Before she’d come here, Thora had gotten in what her counselor Melanie would call a bad spiral.

It was the afternoons that did it, three o’clock like a kind of death knell, the house seeming too still, too many hours of sunlight left in the day. How had Thora even started going to the chat rooms? The last time she had been in a chat room was in high school, sleepovers where girls crowded around a desktop computer and wrote sickening things to men, all of it a joke, then furtively masturbated in their sleeping bags. Or at least Thora had. And now she was back, typing in a username.

Thora18.

How quickly the messages had come in:

Hey Thora! Cute name Asl

Asl

Wanna chat Asl?

Are you 18 or 18 isshhh

It amused her, on her laptop in bed, her husband at work, to reply to these men. To conjure an eighteen-year-old that did not exist, an eighteen-year-old that Thora had never been, certainly: blond, blue-eyed, a member of the cheerleading squad. Did high schools still have cheerleading squads? Had they ever? It didn’t matter how ridiculous the things she said were, how big she made her tits, how short she made the skirt of her supposed cheer uniform, the men seemed to believe, wholeheartedly, that she was real. A ludicrous illusion they were building together, and she found she enjoyed the back and forth. Pretending not to know why the men were chatting with her. Writing hahahaha whenever they brought up sex. What’s that, she typed when someone mentioned double penetration. When they asked her pointed, leading questions about her real age, she finally agreed that she was, in fact, only sixteen.

They were ecstatic, writing back instantly, the sudden use of exclamation points like cardiograms from their throbbing erections:

I won’t tell babe don’t worry!!!!

Her stupidity delighted these men. They had found her, at last: a teen cheerleader who wanted to learn about sex, who wanted to learn about it from them! Too stupid to understand what they were taking from her!

After a while they wanted photos. She ignored the requests, usually, closing the window, but then she thought, why not?

She spent a good hour on the bed, trying to take a photo with her face mostly hidden, a photo where she didn’t look thirty-five but instead looked like a teenager: a finger in her mouth, her tongue peeping out like a little cat. Her tongue looked strange, too pale, but if she used a filter, one arm covering her nipples, she might look eighteen.

The men loved the photo. But then they wanted more.

Are you shaved?

Oh ya, she said. She was not.

How many dicks have you seen.

Um, she would type. 2. Is that weird?

Have you ever had a boyfriend?

No, she typed. I wisshhhhhh!

Amazing how this ate up the afternoon, four hours passing without Thora looking up from the screen. She had missed two texts from James.

If she had better friends, she would have told them about what she was doing. Or if James was a different kind of person. Because wasn’t it sort of funny? She had an entire run of photos of herself on her phone now: bending over, the seat of her underwear pulled tightly across her ass, pictures of her face from the nose down, a nipple between her fingers. They all wanted a pussy shot: she found one off the internet to use. She sent the same photo every time, so gradually she began to believe this bare pink pussy was her own pussy, and in fact began to feel proud of just how perfect this pussy – her pussy! – was.

She had never been the focus of so much attention. So many men trying to coax or trick her into giving them what they wanted. And that was the part she liked best, the knowing/unknowing – it wasn’t possible to summon artificially, role play wouldn’t do it. It had to be real.

She only hated them when they got mean: when she told them she had to go, and they typed back, furious.

Are u fucking serious just help me cum pls

Pls

Im so hard

Bitch

When Thora got bored of talking to the same men, she started signing in under different names. Usually under James45. Sometimes DaddyXO. She talked with the men, pretended she was a man, too, and they sent her photos of teens in bikinis at public pools and she sent them photos of herself.

Such a whore, she typed. Little teen whore.

Mmmm fuck, a man typed back. Love those teen tits.

It seemed obvious that the photos of her were not photos of a teenager, but no matter. Their wish that the tits belonged to a teenager was so strong that it created an alternate reality. She had never been so excited: seeing herself as these men did, some unformed idiot who needed to be fucked. Her sheets smelled like sweat, all the curtains drawn. She didn’t eat for whole days.

‘You’re so wet,’ James said one night, surprised, when she put his hand in her underwear. But then they had sex the way they always did, James coming on her stomach, his body jerking in a series

of convulsions, as though he were being riddled with bullets at the O.K. Corral.

It had all seemed funny except that, truly, she would rather do this than anything else: run the usual errands that kept things in motion, see James, have dinner with him. It was like having a calling, finally, the way she had once imagined she might. A life organized around a higher goal. While James slept, his back turned to her and the covers kicked off, she typed furtively on her phone to men who sent photos of dicks, sometimes tiny squibs of flesh between massively fat thighs, sometimes overlarge penises with the porn watermark visible in the corner.

Wow, she always typed. I don’t know if it will fit.

That was not the reason she had ended up at the Center, exactly, the chats, but it hadn’t helped.

There was a hike in the morning, before the temperatures got unbearable. On the drive to the trailhead, Melanie had turned the radio to a Christian talk station Thora mistook for NPR until they said ‘resurrection’ one too many times.

Thora scrambled around the boulders, up through the dust and the sage. She drank lukewarm water; Melanie passed out protein bars. Last session, someone kept mashing these into coils and leaving them in the urinals, or so said Ally, a veteran of the program. It was a real problem, fake shit being essentially as difficult to clean as real shit. Was there a lesson there?

By the time they got back, G. had already arrived.

No one had known he was coming. He looked, if anything, exactly like the person in the newspaper photos – froggish, squashed, well fed. For all five seasons of his show, he had been clean-shaven, ruddy in his apron and concert T-shirts, big moony face damp with steam from whatever was cooking on the stove. Now he’d grown stubble, white, extending beyond his jawline to his neck and cheeks, giving his face the semblance of a shape. He wore a baseball hat and the same baggy clothes as the rest of them – sweatshirts, pants with soft waists. Their days were considered difficult enough that whatever energy they may have once expended on buttons and zippers was now worth diverting elsewhere.

Men and women were kept separate except for lunch, which most people ate in their rooms anyway. G., surprisingly, chose to eat at a shaded picnic table by the pool, close enough for Thora and Ally to study his froggy face for signs of evil, watch him pick at a sweet potato drowned in soy sauce. Did he eat the sweet potato in a particularly evil way?

The staff allowed them their benzos and SSRIs as long as their home doctors kept the prescriptions current. Things like this made it hard to believe that the people who worked there actually thought they were helping anyone. Ally and Thora sometimes swapped meds for fun; Thora took one dose of Ally’s Lexapro and went into what felt like a light mania, pedaling the stationary bike for a solid hour, then eating ravenously, spilling salsa verde on her robe. The night that G. arrived, Ally took someone’s Ambien but stayed awake, filling out her Dialectic Behavioral Workbook.

What are three concrete changes you can make in order to improve your life?

She showed Thora her answers the next morning, written in loopy Ambien scrawl:

1. Buy puffy white sneakers

2. Double pierce my ears

3. Fuck G.

Addled as she’d been on a sedative-hypnotic, Ally brought up a good point: who was G. gonna fuck first?

G. was assigned Robert as his sober coach, tiny Robert who told everyone with pride that he had built the woodfired pizza oven at the Center with his bare hands. ‘With the same clay the Mayans used,’ he said. No one asked any follow-up questions. Robert wore flip-flops, which seemed at odds with his desire for everyone to call him Coach.

Robert was appalled by their lives, in an exciting way – he’d worked for the government before, for institutions, so people having money the way people like them had money seemed to him like a cosmic joke. He tried to engage one of the business guys in an earnest debate about fracking, tried to explain the problems with a possible Bloomberg presidency. Thora would hear his voice from across the pool: ‘I can see where you’re coming from, man, but have you ever considered –’

Robert stayed close to G.’s side, murmuring into his ear quietly enough so no one could make out what he was saying, though of course Thora and Ally tried their best, filled in the blanks, imagined all manner of foul behavior turned into a narrative, spun into a story of good and evil.

During that afternoon’s phone hours, Thora called James. The phone room in the main building was busy, so she made the call in Robert’s office, an adobe outbuilding on a concrete slab. Out front, there were half-barrels on the porch where Robert was growing gray stalks of kale; a wind chime made of abalone shells hung from the eaves. His white dog was pregnant: she lurched heavily on her chain, then circled back to sit in the shade.

Thora’s cheek was sweating where the phone was pressed to her ear.

‘Does anyone even speak to him?’ James asked. ‘Monster,’ he said, under his breath. Though Thora could sense it, too – James was excited. They all were. Thora had read every disgusting thing G. had done: every hot-tub dick graze, the Fleshlight in the green room, drugged-up gropes of cowering PAs in sensible flats. With his presence, the communal mood heightened a few degrees. The only other resident who conjured any frisson was a baseball player who’d been caught jacking off in an afternoon showing of Despicable Me 3, but that was nothing compared to G. Thora and Ally tracked G.’s every choice and activity, took any opportunity to smile at him or sit near him at meals. G. drank cucumber and kale juice in the morning. G. took Pilates from a private instructor in town. G. was trying to avoid nightshades after his food sensitivity test. G. appeared, to Thora’s eye anyway, to have gone down a pants size.

‘He keeps to himself,’ Thora said. ‘We’re all just trying to do our best here.’

There was a silence. She assumed they were both thinking of G.

‘Well,’ James said. ‘I’m proud of you. Really.’

Thora was on Focalin. Or had been, until they found out she had been snorting it off James’s iPad, the iPad he loaded with podcasts about political crimes and interviews with precocious teens starting businesses. She’d tried listening to one of them once, one of James’s beloved podcasts: when had life become so dull, an extended social-studies class where you were supposed to summon interest in the workings of corporations, the minutiae of historical events, spend your free time cramming for a test that didn’t exist?

Everyone was suddenly trying, so very hard, to learn things.

Group was kept separate by gender, and was supposedly confidential, another of the ‘rules’ that turned out to be nothing more than a half-hearted suggestion: Russell told Ally and Thora everything from men’s group when the three of them drank mugs of weedy chamomile out on the South Veranda.

‘He cries almost every time,’ Russell said. Ally knew Russell from her last stay here, a year ago.

‘No,’ Thora said.

‘Truly. He doesn’t get into it. But just says he’s here to learn. He knocked over my water bottle and apologized. Like, almost with tears in his eyes.’

Ally leaned back on her elbows. ‘Probably fake tears.’

‘Robert doesn’t even make him go into detail. Which is not exactly fair.’

But G. didn’t need to go into details, didn’t need to unspool all the stories for the rest of them: they already knew everything. When Ally was asleep, Thora sometimes rubbed herself against her palm, imagining the bulk of G.’s body behind her, that belly, formidable from years of public gastronomy, slapping against her back. It only worked if she imagined G. believed he was taking something from her.

‘Have you talked to him outside of group?’

‘Nah,’ Russell said. ‘But guess what?’ He was almost gleeful. ‘I have a UTI. My deek’ – he pronounced it like that – ‘hurts,’ Russell said.

‘I don’t believe you,’ Ally said. ‘Guys don’t get UTIs.’

‘Oh, it’s for certain,’ he said. ‘The doctors were surprised, too.’ Russell was proud in his insistence: blessed by rarity. His dick was like no other dick. And he did have a UTI. Thora had never heard of this happening before, but that’s the way the spring had been going.

The next night, Ally was reading her doll-maker book. Occasionally she pressed a hand to her heart, overcome. Russell had brought Thora a magazine from town, but she’d seen it already. A page of various celebrities with cellulite blurring their thighs. A different celebrity recording everything she ate in a day. Like all of them, around 3 p.m. the celebrity ate a handful of almonds as a snack. A cut-up bell pepper with hummus. Living that way seemed to require skills that Thora lacked. The ability to take your own life seriously, believing that you were a solid enough entity to require maintenance, as if any of it would add up to something.

She looked up from the magazine when there was movement on the sill.

‘Shit,’ Thora said, ‘gross.’

Ally glanced up from her book. Together they considered the moth on the sill, the dry feathery beast. It must have got in through the open window. The moth was sleeping, at least, its wings folded in prayerful repose. ‘What should we do about it?’

‘Just try to shoo it out the window?’ Thora said. Ally put down her book.

‘Want to see something?’ Ally said, unzipping her little pink purse, flicking her vial of insulin expertly. ‘We did this at diabetes camp once. No bubbles,’ she said, ‘that part is important.’ She got up on her knees, shuffling to the sill. ‘Are you watching?’

Thora rolled her eyes. ‘Yes.’

Ally grasped the moth firmly between her fingers. It barely moved.

‘Watch.’

With impeccable swiftness, Thora injected the fat moth body with her insulin – the moth vibrated a little, awake now.

‘What the fuck,’ Thora said. The moth spread its wings before starting to fly around the room, crazily.

They both shrieked. The moth slammed into the wall and dropped dead. Ally, inexplicably, started laughing.

‘Sick,’ she said.

Ally and Thora were G.’s most likely targets, the only ones in his preferred demographic. Most of the women at the Center were older – burned-out executives, plastic-surgery recoveries, legit addicts who forestalled reality a little longer by wasting some soft money here on what amounted to a very expensive hotel stay. Thora studied herself in the bathroom mirror, picking the dead skin from her chapped lips. Would G. find her attractive? Ally was younger than Thora, which, historically, would have been a plus for G., but diabetes kept her pale, and her hair had gone a little green from the chlorine, her brows furring out without her tweezers.

Before lunch, Thora changed into a tight tank top, yoga pants that had a perverse seam in the crotch. She let her hair down at the picnic table, idly brushed it with her fingers over one shoulder. Ally was on some tear about how her father always told her she was beautiful and never smart, and wasn’t that sort of fucked up? Thora wasn’t paying attention: she was watching G., deep in conversation with Robert. He’d barely touched his stone fruit caprese salad.

G.’s daughter was definitely staying nearby. There were sightings. Russell had seen her on one of his excursions to town: Russell was desperate for mushrooms, trying to cadge some off the men with sunburned necks who rode BMX bikes along the main street, their bicycles evidence of suspended licenses from DUIs.

Later, Thora watched G. across the pool reading Robert’s self-published book on accountability, pausing to balance it on his T-shirt-covered belly. Thora rubbed aloe sunscreen on her legs, slowly. Swimsuits weren’t actually allowed by the pool except during gender-restricted swim hours – but no staff seemed to notice. But had G. noticed? Was G. going to come over? No, he was reaching for a pen, he was underlining something. When he got up, it was only to refill his water bottle, do a little yogic stretch, clasping his arms behind his back, straining his belly tight. In the last two days, he had started wearing a bracelet made of wooden beads around one wrist.

‘Very spiritual,’ Russell said.

Robert’s dog had finally had her puppies: six squirming, mostly silent creatures with slitty eyes and little hamster claws. Robert plugged in a heating pad, nestled it among blankets in a cardboard box, though it was April, eighty degrees on Easter.

Robert set up the box in the common room. Thora assumed the puppies were meant to teach everyone about fragility, about caretaking. Ally held one to her chest, stroking it with a single finger.

‘Tiny,’ Ally cooed. ‘Look at their little noses.’

Thora held one, too. ‘So cute,’ she said, unconvincingly. When one of the puppies took a shit in the box, the mom ate it.

At check-in, Melanie asked if Thora was aware that she was wearing exercise clothes outside the gym area. She asked if Thora was aware that the dress code asks us not to expose our shoulders. Melanie asked Thora to

Scan her body,

Assess her feelings,

Locate the discomfort.

What were her feelings? Mostly Thora felt drowsy – there in the carpeted room, the sun coming through the big windows.

Melanie wanted to talk about Thora’s mood journal.

‘If we can start to notice a pattern,’ Melanie said, ‘you’ll be able to have a little more control.’

There were dozens of plants behind Melanie, their glossy heart-shaped leaves twisting across the sill. Someone had to water them. Every week. The thought of anything needing regular care and upkeep suddenly made Thora even more tired. She crossed and uncrossed her legs. Melanie’s cell phone rang.

‘I can show you how to turn off the ringer,’ Thora said, when Melanie’s phone rang for the third time. Did her voice sound as hateful as she felt? Melanie didn’t respond. Melanie was looking at her with concern.

‘I’ll consider these questions in my journal,’ Thora said, finally.

Melanie both cared about Thora and did not really care – Thora saw Melanie’s face toggle between these two absolutely true things.

After breakfast, Russell, Ally and Thora saw G. and Robert leave for town. The huevos rancheros had solidified on Thora’s plate, the beans now mortar. She’d eaten the fruit, enough to avoid a talk with Melanie, and Russell would likely finish the rest anyway. G.’s baseball cap was pulled low, his gait shuffly from his sandals. He paused to apply lip balm from a plastic sphere. No one knew why G. went into town so often, though maybe it was just to see his daughter. G. was working on a screenplay, they heard, or a memoir. Russell claimed to have shown him how to download Final Draft.

‘But why is he allowed to have a laptop?’ Ally said. ‘If he tries to rape us, can we borrow his laptop?’

‘Do we think he’s going to jail?’ Russell said.

Thora had read more about G. in the Business Center, the computers signed in for thirty-minute web sessions. Their servers blocked porn sites, so it was never busy.

‘Not likely,’ she said, with authority.

‘It’s pretty old stuff, mostly,’ Ally said.

‘Still.’

‘Not all of it,’ Thora said. ‘That one girl was basically a few months ago. At the Super Bowl thing.’

‘But didn’t she just say he tried?’

Russell stared darkly at his plate. ‘That’s just as bad.’

Ally and Thora glanced at each other but stayed silent.

G. put himself in charge of the puppies, or maybe Robert did; at any rate, all of a sudden there was G., squatting by the box in the common area, spooning cottage cheese into a bowl. Up until then G. had only seemed to interact with Robert, but now people were reporting conversations, G. chatting away with whoever came by to look at the puppies.

It was the first time Thora had encountered him mostly alone: there was a man playing solitaire at one of the tables, Blue Planet silently on the TV, but other than him and G., the common room was empty. Thora dropped her shoulders, ran her tongue along her top teeth.

‘Cute,’ Thora said, squatting to G.’s level. ‘Puppies.’

‘Their eyes still won’t open for another week or so,’ G. said. He glanced up at her; Thora strained to detect some sinister ripple in his look, but it was too brief.

‘Is it okay to hold one?’ Thora asked.

‘Is it okay, Mama?’ G. said, directing the question at the big dog panting away. Bizarre. Thora kept a mild smile on her face while G. scratched the dog’s chin energetically. ‘Sure,’ G. said, still looking at the dog. ‘Just let her see that you have it. That you aren’t taking it away from her.’

Thora settled onto her knees, aware of how close she was to G. He had definitely lost weight, but his face was still recognizable: the soggy skin around his eyes, the coarse stubble, thick ears. His hands were immaculate, he wore no wedding ring. His wife – a former manager in G.’s restaurant group – had, obviously, initiated divorce proceedings.

Thora reached into the box, going for the closest puppy. It was warm, mottled with brown, the size of a burrito. She held it with two hands, knowing G. was probably watching her.

‘That’s the fattest one,’ G. said. ‘Though they’re all pretty healthy. No runts.’

The puppy’s heart was racing, its head rearing around. Thora tried to hold the puppy gently. ‘Wow,’ she said. ‘Imagine their tiny little hearts in there.’

It was something Ally had said about the puppies; G. murmured thoughtfully in response.

When Thora introduced herself, she looked straight into his eyes, smiling. ‘I’m Thora.’

‘I’m G—’ he said, not smiling back, though he didn’t seem unfriendly. Thora told herself he was likely being careful. She glanced at the man playing solitaire to see if he was watching them. He wasn’t. G. scooted the bowl of cottage cheese closer to the dog. She didn’t respond. Thora placed the puppy back with the others, its little claws skittering on the cardboard.

‘Eat, Mama,’ G. said. The dog was lying there, panting.

‘Is she okay?’

‘Just tired.’ G. spooned a little cottage cheese out with his finger. The dog licked it, finally, and G. brightened. ‘There you go, Mama,’ he said, ‘easy.’

Thora stayed kneeling like this was all very fascinating. And maybe there was a weird thrill in watching the puppies nurse, the pure creaturely fact of it.

‘She’s been hiding the puppies,’ he said. ‘Robert found one in the couch cushions yesterday.’

Thora had heard this story already but acted like she hadn’t.

‘The couch cushions?’

‘I guess it’s ’cause she’s trying to protect them, you know? Good thing no one sat on the pup.’

‘Yeah.’ Thora stayed quiet for a little longer but he didn’t speak again. She got up.

‘Nice to meet you,’ she said. She cocked her head slightly, her shoulders back, readying herself for his gaze.

‘You too,’ he said. He didn’t look up.

It rained the next day, a rare steady rain. The air went a bit blue: Thora closed all the windows in their room. The staff was taking a few of the vans into town, for anyone who wanted to go to the mall.

‘Wanna come with? We can see a movie?’ Ally said. ‘Or maybe we can get my ears pierced?’

‘Sorry,’ Thora said. ‘I’m just gonna hang here.’

Ally seemed suddenly lonesome, girlish, her fingers grazing her earlobes. ‘We’re gonna go to the bakery. You want me to bring you back a cookie?’

‘I’m good,’ Thora said.

Thora wanted Ally to leave, but when she finally did, Thora felt guilty. Thora took an apple to their room, ate it all the way to its meager center, and spat the seeds on the floor.

Thora hadn’t seen G. leave with the others, but he wasn’t in the common room, either. There was a girl Thora knew from group, knitting on the couch. She nodded, Thora nodded back. The puppies were mostly asleep. So was the dog. Ally said the dog had been carrying the puppies around in her mouth, her jaw closed on their necks. Thora picked up one of the pups – it barely made a sound. A little chirp, like a bird.

Thora put the puppy in the front pocket of her sweatshirt. She kept both her hands in there, too, feeling its aliveness. She got wet from the rain, walking from the common room to the residences, her sweatshirt darkening. But she kept the pup dry. The halls were empty. She let the puppy go on Ally’s bed. It was blind, squirming at nothing, against nothing. It couldn’t go anywhere, could barely wriggle forward.

Thora petted the puppy with one finger. It was nice to be in here: the rain on the windows, the hallways quiet, and this animal, like a little soul that had wriggled loose from a body. If there were such things as souls, wouldn’t they be blind mewling creatures about the size of a burrito?

She didn’t know how much time passed. Maybe he knocked on the door, first, but Thora didn’t hear. And there G. was, standing in the doorway, in his baseball hat, his polo shirt. His face was agitated. When he saw the puppy on the bed, his shoulders dropped.

‘Fuck,’ G. said. ‘We were really worried.’

Thora sat up, crossing her legs. He had sought her out.

‘Yeah,’ she said, ‘sorry. I mean, the puppy’s fine, though.’

G. took off his cap to run his fingers through his shanky hair, flashes of bare scalp catching the light.

‘They really shouldn’t be away from their mother.’ His voice cracked. Was he about to cry? ‘She’s freaking out.’

‘I thought it was okay. I didn’t know,’ Thora said. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Is she okay?’

Thora looked at the squirming animal.

‘Did you think,’ Thora said, ‘I would hurt it?’

‘It just shouldn’t be on the bed like that, she might fall off.’

She had arranged herself so, if he wanted, he could look at her body, consider it, but it was clear he wasn’t even clocking Thora. She let the silence grow.

It took Thora a moment to register his expression: he wasn’t interested in her. Was he disgusted with her? As if she was the bad one! Didn’t he know that Thora knew every awful thing he had done? Every darkness that hid in his heart had been exposed.

He moved to pick up the puppy. Thora held it to her chest.

‘You’re not supposed to be in the women’s dorm,’ Thora said. Her voice was cold.

At the tone of her voice, G. stopped, suddenly, his hands flopping at his sides.

‘I was just,’ G. said. ‘The girl told me you took the puppy and the dog was just, you know, really freaking.’

‘You should not fucking be in here.’

After Robert arrived, furious to find G. in the women’s dorm, G. had been classified as a more serious case and shuffled to an all-men’s program in New Mexico. Thora recounted the story at dinner, Ally slowly chewing at her bottom lip.

‘My heart was beating so hard. I was actually’ – Thora lowered her voice – ‘terrified.’

‘Poor girl,’ Russell said. ‘You shouldn’t have to deal with this.’

‘I mean,’ Ally said, ‘he’s doing this stuff even here?’

‘He shouldn’t have come into your room.’

‘I honestly don’t know,’ Thora said, ‘what he would have done if Robert hadn’t shown up.’

Russell massaged Thora’s shoulder, Ally leaning against her.

‘We’re just glad,’ Ally said, ‘that you’re okay.’

Their faces were concerned, their voices soothing, but, Thora noticed, their eyes were bright.

That summer, Thora – returned to her home, returned to her life – finally read the book about the doll maker in World War II: Ally had been right. It was a great book. Thora cried when the doll maker’s daughter found the carved birdhouse in the attic, proof that her Nazi lover remembered her after all. Thora read the last scene aloud to herself, the green buzz of June beyond the windows of the house, the house where she lived with her husband, and there was something in the book that made being a different sort of person seem possible. It was a book about people, how people should help each other, and really, wasn’t that what life was about? Weren’t people basically good?

She resolved not to go on the chat room.

She resolved to brush her teeth before James got home. The feeling lasted for a little while. Then James was late for dinner, and there, in the dining room, the sky outside going dark, whatever she had felt earlier was already slipping away, already gone.

James was looking at her.

‘What?’ Thora said. ‘Did you say something?’

James shook his head, shrugged. He had a sty making its angry way to the surface, swelling his eyelid unpleasantly.

They watched the news in bed, James holding a warm tea bag to his eye. G. had declared bankruptcy. G. had avoided criminal charges but was due to appear in court for a scheduling conference for the first civil case the next week. There was footage of him, harried, exiting a car, a benzodiazepine smile on his face.

James put the tea bag on the nightstand. His eye looked just as red, only now the surrounding area was damp, too, the skin puckered by heat and moisture.

His hand crept toward his swollen eye, then paused in midair. She saw his desire to do something, to scratch his infected eye, then saw him understand that he should not do the thing, saw him remember that he had been told, expressly, not to touch his eye. And for James, that was enough – he did not do the thing he wanted to do, his hand dropping back to the blanket. Instead, James blinked hard, blinked deliberately. He smiled at her, a tear dripping from the eye he offered to her for inspection.

‘Any better?’

![]()

Artwork © Elisabeth McBrien, California Afternoon, 2017, New York Academy of Art

What week of lockdown are we in, as I write this? I hardly know any more. Quite early on, walking at dusk, I heard whooping and clapping from houses far away, the sound carried on the wind. I stood in a field thinking of all the people who have died, and the dedication of those who had cared for them.

But soon everything that had felt so tragic and dramatic to begin with – thousands of people ill and dying, the great pause, the intense dreams, the solidarity clapping – came to feel normal. Lethargy took over, until that too wore away. I suppose most of us got used to our restricted worlds, moods and thoughts blooming and fading, and the almost imperceptible succession of phases, to do with how the light falls into a room, say, or how a new particular thing – a book, a film, a habit – establishes itself.

In Britain, a question is taken from a member of the public in the daily political briefings. A hushed voice reminds us that the Cabinet member present has not seen the question in advance, as though this were a political satire or a rehearsal, a performance of national tragedy rather than the real thing.

Alone, we stare moodily at our screens, then join meetings and smile with relief when people we know look back, face to face.

‘What have we learned from the pieces coming in during this time?’ I asked at an editorial meeting.

‘Maybe,’ someone answered, ‘that many of us already had a fragile connection with the outside world.’ It must be partly the nature of writing life, but the pieces in this issue all, in some way or other, speak to confinement or escape. Emma Cline’s story is set in a closed center, ‘not quite rehab but some way station before rehab’. The inmates include a famous TV chef: ‘Thora had read every disgusting thing G. had done’; ‘every hot-tub dickgraze’ and ‘drugged-up gropes of cowering PAs in sensible flats’. Thora herself had created teen avatars for her own gratification, not the only reason she is here. The atmosphere, or rather Thora’s state of mind, is dense with cynicism, seduction and loneliness; too dense and complex, one senses, for the nature of the care (vitamins and counselling). Ann Beattie’s protagonist opens a literary magazine and is shocked to see a photograph of her younger self with a friend and their college professor, illustrating a piece written by her former friend, an essay masquerading as fiction, inventing a love triangle in cadences that – adding insult to injury – seem an imitation of her own way of speaking when younger. Adam Nicolson’s story of a seventeenth-century English village struck by the plague reminds us how close we are to that world still, forming theories from rumours and portents, fleeing, drinking, burying the dead.

But we are also learning to pay attention. To properly see. Here is Leanne Shapton, painting interior scenes from her flat in New York, and describing what she sees. Here is Teju Cole, observing trees from walks in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Michael Hofmann, noticing ‘drifts of pollen in the gutters and on car windscreens, like gold dust’, in Gainesville, Florida.

Time is the gift, but of course there are bigger issues to grapple with; questions of freedom and captivity, of responsibility and existential threat. I could go on, finding words for dysfunctional or ineffective governance. If I don’t, it’s not from lack of interest, exactly – but the spittle of the spittlebugs on a thousand stalks of grass this morning seems more real to me now; or the hornet searching every corner of my room before it leaves, duty done. The light filters through the leaves outside my window; something moves – a dragonfly? No, a spiderweb, swaying in the wind.

I am not talking about beauty. Barry Lopez has described how observing a scene (a bear, say, feeding from a carcass) without automatically collapsing the moment into language, deepens the experience of seeing. His message applies to this pandemic too. I hope that by the time you read this, the lockdown will be over. Until then, I will be mindful of Lopez’s rules: ‘Perhaps the first rule of everything we endeavor to do is to pay attention. Perhaps the second is to be patient. And perhaps a third is to be attentive to what the body knows.’

Artwork © Leanne Shapton

The post Introduction appeared first on Granta.