Ellen Coon has been collecting oral histories in the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal for over thirty years, recording the stories of the Newar people, an Indigenous community based in the region. Isabella Tree – our guest editor for Granta 153: Second Nature – wrote her first book on the Living Goddess tradition celebrated by the Newars. They came together early this year to discuss the Newar approach to the divine feminine and the care for the land it encourages, while considering what we can learn from this community through our own commitments to building a sustainable natural environment.

Isabella Tree:

We know we have to fundamentally change our relationship with nature, if we’re to address all the environmental crises facing us. And in this issue of Granta, Second Nature, I wanted to explore how other cultures view the land and living things. Especially those that have managed to strike a balance, to live sustainably for hundreds if not thousands of years. And one of the most intriguing cultures, I think, is the one that has a lot to say about human relationships with nature – that of Newars in the fertile Kathmandu Valley in Nepal, in the foothills of the Himalaya. Originally a Buddhist society and deeply spiritual with strong ties to farming as well as to the arts, I first encountered them in my teens travelling during my gap year. And that introduction eventually resulted in a book I wrote about the Living Goddess tradition in the Kathmandu Valley, a book that took me only fourteen years to write. And that is how I came to meet the wonderful Ellen Coon, about fifteen years ago now. And I soon realised how deep and extraordinary her understanding of Newar culture and their belief system is.

And so I wanted to talk to you, Ellen, to try and get a deeper understanding of this extraordinary culture that we both know and love, and consider how it has perhaps lessons for the way that we might look at nature and where we’ve gone so wrong.

But first, I thought you could introduce yourself and explain what took you to Kathmandu in the beginning. And what led you down this amazing path and how we met.

Ellen Coon:

I first went to the Kathmandu Valley in 1970, when I was a nine-year-old girl. My father was a diplomat. I was incredibly lucky, because he was posted to Kathmandu, in Nepal, not once, but twice. First in 1970, for three and a half years, and then from 1981 to 1984, when I was in college.

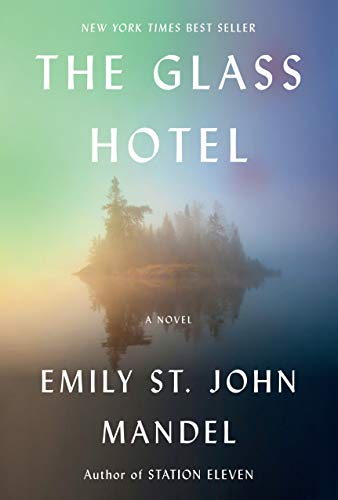

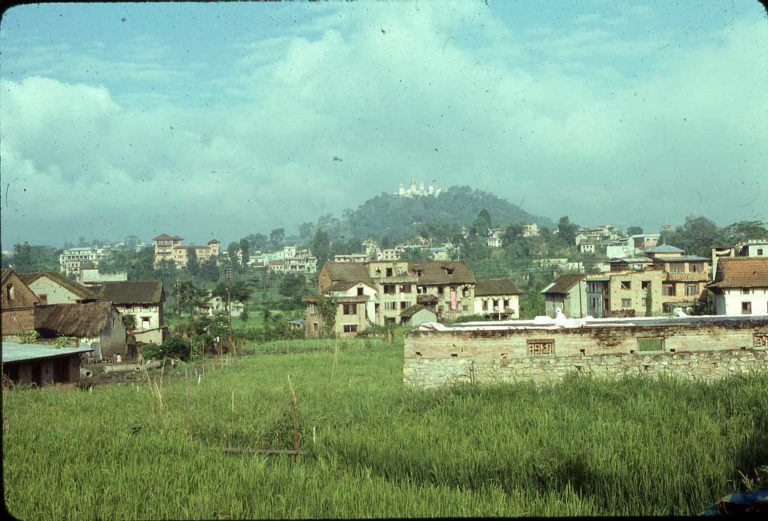

When I got to Kathmandu as a nine-year-old, I found it incredibly beautiful. It was absolutely vivid, an electric green, the green of rice paddies. The whole valley was intensively cultivated by hand, really gardened rather than farmed, with rice being the primary crop, sometimes more than one crop a year, with patches of forest and trees, sacred forest. And the three major towns of the Kathmandu Valley – Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Patan – were still these jewel-like antiquated cities, in the middle of all this green, ancient and rich, cities like honeycomb or coral reef.

Nepal has had some very strange and xenophobic rulers, the Ranas, who had established a dictatorship in the nineteenth century, and they had kept Nepal closed to most foreigners, almost all foreigners, certainly Westerners, until the monarchy staged a coup and reasserted power in 1951. And then the doors sort of opened. But in a lot of ways it was still a closed system, the Kathmandu Valley was a closed system. And 1970 was only nineteen years after it had begun to open.

I fell in love with the Kathmandu Valley almost immediately, as a child. I felt that there was something beautiful and true there that the rest of the world should know about – and I still feel that way. I started recording the stories of older Newars, mostly women, over thirty years ago. The rapid pace of change there has only made this work feel more urgent. A kind of collective remembering of what was a sacred landscape, where a rich human culture didn’t destroy nature but on the contrary created the conditions for an equally rich biodiversity of plants and animals to flourish.

Kathmandu c. 1980 © Todd Lewis

Kathmandu c. 1980 © Todd Lewis

Tree:

And how did we meet? Do you remember?

Coon:

I think it was 2005 or 2006. I had a Fulbright scholarship, and I had been awarded a grant to expand the research that I had done earlier collecting oral histories from particularly religious Newar women, to try to understand their experience of Newar tantric religious culture. The Newars are the Indigenous inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal.

I was living in a big cement bungalow with my husband and children on Museum Road near the Swyambhunath stupa. It was the spring, and we had lunch together outside in my garden under a flowering tree. You were researching your amazing book, The Living Goddess, and both of us were trying to understand the nature of the culture around us, which was very compelling, but difficult to put into words.

After we had lunch, I took you to the masked dances in Naradevi, it was during the Pahan Charhe festival, which is a springtime festival that involves a lot of goddesses on the move, street festivals. We went to see what’s called a Pyakhan or a masked dance near the Naradevi Temple, which is performed by farmers who each assume a hereditary lifelong role as a particular goddess. Possessed by the goddesses whose masks they wear, they do these long, slow dances while huge adoring crowds worship them. And that definitely put us into a nonplussed, wordless state.

One of the things about people who learn from and study with Newars is that they have a very hard time putting what they’re learning into what we would call coherent words. Because it really is a different system of thinking and a different perspective on the world. It gets even verbose people temporarily dumbstruck.

Tree:

Yes, I certainly felt that writing the book [The Living Goddess: A Journey Into the Heart of Kathmandu]. In a way, it sort of feels like a betrayal if you’re just beginning to understand and to try and put into words on a page. Because something that is so different from our way of seeing is very difficult, I think, to express in written book-form. That is also why, I think, it’s much easier to talk about it.

So, how shall we begin? I wondered if you could give us an idea of how the relationship with the land really underpins everything in Newar culture, in the belief system, that connection with the landscape.

Coon:

Let’s start with the Kathmandu Valley. When Newars talk about themselves and their lives, the Kathmandu Valley and places in the Kathmandu Valley, are always an integral part of their story, who they are as people. In fact, now that Newars have started to travel all over the world to live and work and study, it’s an interesting question: who you are when you are taken away from a place that that basically forms the marrow of your bones.

As I said, the Newars are the Indigenous inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley. That’s how they see themselves. And they have their own Tibeto-Burman language, their own elaborate art and architecture and religious civilisation that are said to be thousands of years old. Who can really say. But definitely the Kathmandu Valley has been continuously inhabited for thousands of years. In this way, they’re different from people from the surrounding hills. Linguistically, culturally, in every way, including in their religious civilisation, their particular forms of Hinduism, and Buddhism.

Tree:

And the Kathmandu Valley is incredibly fertile, isn’t it?

Coon:

Yes, the Kathmandu Valley is a lake bed; it used to be a lake in prehistoric time, which is also mythic time. And the soil is extraordinarily fertile. The Newar attitude toward the Kathmandu Valley is that it’s a sacred landscape. It’s holy ground. And it’s this pulsating heart of the sacred geography of the Himalayas, which is a broader sacred geography to Hinduism and Buddhism.

Tree:

One of the things that always struck me was, I was told that it was a taboo in the Newar belief system to plough. That ploughing would be like tearing your nails down your mother’s face, the earth being the body of your mother, the Mother Earth. That’s something that I’ve thought about a lot recently. Particularly editing this issue of Granta because we’re only just now beginning to understand, in the European tradition of agriculture, how bad it is for the land to be ploughed, and that every civilization, from the Romans to the Mayans to the Egyptians, have fallen because they have abused their soils and degraded their land.

I think it is incredibly interesting to have this taboo in the Kathmandu Valley, where there is a particularly sort of friable soil, which is easily prone to run off in the monsoon or to being blown off by the winds in the dry season – it’s a way to understand that ploughing is bad for that soil, that it shouldn’t be done, and it is expressed in this spiritual way.

And yet, while this is a taboo and a tradition that goes back centuries, in the last few decades, their whole tradition is beginning to unravel. The Kathmandu Valley itself is changing dramatically as this farmland disappears fast. But this is something we’ll return to. For now, I wonder if we could take a step back and just see it through your eyes when you when you first went there. What was it like?

Coon:

I was surrounded by what you would call the divine feminine. There were shrines and temples everywhere. There were male deities, but by far the majority were goddesses. That makes an impression on a nine-year-old girl. And it wasn’t just that there were images of goddesses and others everywhere, beautifully exquisite images, paintings, bronze stone. But living women and living girls and living people could, in fact, embody deities and divinity. So the Kumari, about whom you wrote your book, was a little girl, also known as the Living Goddess, who was of national importance; she was called the Royal Kumari. And she was a little girl from the Buddhist Newar community, and embodied this very powerful female deity, who is seen to protect and really rule the whole country of Nepal. During her annual festival, my father had to squeeze into his tight pants, and his morning coat, which didn’t fit him very well anymore, and with the other diplomats was obligated to go and attend her during part of her annual festival. That made a huge impression on me.

What I took for granted at that time, was the fact that these cultural riches were embedded in an absolutely thriving natural world. That was filled with flowers and animals and plants and diversity, a great diversity of being. And so when I went back, while I was in college in the early 1980s, I began to get curious in an intellectual way about why I felt such a shock of incredible well-being when I was in the Kathmandu Valley. What was the source of this feeling? When I was a girl living in the Kathmandu Valley, I felt better than well, I felt a kind of thriving that is hard to put into words, a kind of fierce joy. And a lightness.

Samyak festival in Patan, Nepal. Worshipping the dyas, in this case Dipankara Buddhas. © James Giambrone

Samyak festival in Patan, Nepal. Worshipping the dyas, in this case Dipankara Buddhas. © James Giambrone

Tree:

Do you think that was something as much to do with natural beauty of the valley and the integrity of the farming culture at the time, as it was to do with the belief system of the divine feminine, that is such a loss to us?

Coon:

I absolutely do. I think they were completely intertwined. The belief system grew out of the land; and the land stayed looking the way it was due to the belief system.

I became curious about why I felt such intense well-being in the Kathmandu Valley, something I had never felt in the United States or any other Western country.

I was studying religion in college at the time, and in those days, there were some Western feminists and feminist religious scholars who were studying goddess worship in prehistoric times – the work of Marija Gimbutas comes to mind – and studying other cultures saying, ‘Look, if we just stopped this god nonsense, and went back to goddesses, everything would be so much better.’

And I thought, ‘Hmm, well, I’m not so sure it’s that simple.’ But I was interested because I couldn’t help but notice that Newar women were a visible force in society. They were very powerful. They were out, they were visible, they were conducting rituals, they were selling produce, they were extremely important as farmers. Whereas the orthodox Hindus in the hills, the women seemed not nearly as powerful, to my eyes. I thought, well, they’re both Hindus and Buddhists. So what’s different? And I began to learn about the tantric religious movement, and how that had shaped the practice of the Newars. And if you want to talk about what that is, right now, I invite you to.

Tree:

That could be a huge vortex!

Coon:

Okay, so I’ll just go very quickly. It was an anti-ascetic religious movement that took place in India in the seventh or eighth century. The Indian subcontinent, or South Asia, has often been in the grip of very strong asceticism, and a purity-pollution binary, where people are striving for purity and casting out those they consider lower castes, women or animals or all kinds of things, as polluted.

I would say that the tantric religious movement was really almost like the hippie countercultural movement, about celebrating the body. It was a movement of radical equality, and most of all it valorised the feminine. The Kathmandu Valley proved to be very fertile ground for this movement, which was somewhat wiped out elsewhere, or eradicated in India by the Muslim conquests.

Tree:

And not tolerated either by the British. It didn’t fit with their ideas either.

Coon:

Right. So the Newars, the way they practise Hinduism and Buddhism is tantric. And it is infused with the view that the feminine as primary, and that the earth is alive. The earth is sentient.

Tree:

Can you explain a little bit more about that?

Coon:

Yes, I’ll definitely talk about that. According to this view, the Earth is alive; the earth is sentient. Even the soil itself is filled with divine feminine energy. It’s alive, it’s pulsating. And the world is filled, teeming with other beings, invisible and visible. One of the really visible facets of tantric religious culture is this great proliferation of deities, which in the Newar language are called dya. So gods and goddesses or divine beings, but they are not all one.

Tree:

And the wonderful thing about the word dya is that it’s not masculine or feminine, is it?

Coon:

Right. It’s not a gendered word.

And so there’s this great proliferation of dyas, most of whom are believed to be female. But they really arise from this living, pulsating, sentient soil, almost like stem cells of the Kathmandu Valley, this incredibly fertile soil.

I became very interested in dyas, in deity worship, which proliferated all around me. I was interested in where the dyas come from, because these deities could have Buddhist or Hindu names, but they also have local names. They can be traced back to a place.

You could have this beautiful, elaborately carved image of a deity, worshipped with singing, with vermillion and all kinds of food and flower offerings. But that same deity might also be recognized in a big rock in the middle of the field, or clump of dirt.

How is this living pulsating energy kind of erupting in this place or that place? I always used to think, well, how do we know? How do we know that this divine Shakti [primordial female energy], is erupting into a manifestation right there. Some rocks might be put there, and those would be worshipped, and then an image would be carved of a goddess. And that would be put against the rock or against the dirt. And that would be worshipped. And stories would be told. And in this way the same deity would gain many other identities just like you are Izzy and Mummy, and, you know, ‘Isabella Tree, the celebrated author’, all those identities, it’s still you.

I was fascinated by that process. What I often felt Newar farmers were doing, when I was a little girl, and later, was that they were listening. They were listening to something I couldn’t hear.

Jyapu farmer with dya, © Thomas Kelly

Tree:

Is there sense that, in a tantric sense, that farmers were relating their own bodies to the land? That a correlation is happening between sacred places and sites and with one’s own physical body?

Coon:

That’s right. There’s an embodied understanding that there isn’t a division between us and the earth that we come from. We aren’t separate from the earth.

I want to back up a little bit and talk a little bit more about Newar farmers. Most Newars were engaged in agriculture in the past. And there was a hereditary caste, the largest caste of Newars called Jyapu – ‘Jya’ means work, and ‘pu’ means able, and it means ‘very strong workers’ – but they were the backbone of the whole Newar society. And not only were they farmers, but they were highly realised tantric Hindu and Buddhist practitioners. They embodied and practiced this knowledge that there’s divinity in a clump of dirt, but also an intimacy with elaborate proliferations of deity, esoteric Buddhist concepts such as impermanence and emptiness, and lengthy, difficult rituals.

Newar farmers have a hereditary obligation to learn the arts, the sacred arts, painting and sculpting, but especially music and drumming, which are forms of worship. And so they go through an apprenticeship of this intricate drumming that you hear in processions and around temples, because the language of the drums, it’s called dya bhae, or the language of the gods, god-speak.

There is an understanding that the soil is alive and filled with divinity, and every fall before the harvest, there is a three-day fasting worship of the Buddhist goddess Vasundhara who is a goddess of the harvest, wealth and of the earth. She’s dressed in yellow, she can be many-armed. She holds in one hand a sheaf of paddy, rice grain on the stalk, and in the other, she holds the foundational Buddhist text, the Prajnaparamita, which is the perfection of emptiness, the idea that nothing is permanent, nothing stays the same, and that there is no real self.

Jyapu farmers would worship Vasundhara in these elaborate forms, including as these esoteric and very cerebral Buddhist texts about the understanding of impermanence and emptiness. But she is also present in a handful of rice. And Jyapu farmers would also worship her before planting rice, on their knees before a lump of wet mud in the fields. So there’s this understanding of both: that the goddess Vasundhara is a lump of soil, and also something more abstract and personified.

Tree:

I think what you’re talking about is a very intense love of the earth, that we just can’t imagine really. And that intimacy that is felt for the earth is the same kind of intimacy one would feel for other human beings, for all sentient beings, essentially. There are specific days to worship the creatures that are integral to the whole farming system. It’s a very intimate, immediate relationship with living things.

Coon:

The masked dances that you and I went to in Naradevi the Pyakhan, where the farmers were embodying these goddesses, these earth goddesses, territorial and land-based goddesses – I learned the most about these dances from an old Jyapu farmer named Jit Narayan Maharjan. He was already a very old man at that time. And I said, ‘Tell me about these dances.’ And the way he started to tell me what’s happening was to start a fifteen-minute roaring recitation of the names of different divinities. And I started listening closely and I thought, ‘What is this? This isn’t just the names of goddesses.’ He was saying, ‘Flies! Fly goddess, frog goddess, dog goddess, sparrow goddess’ you know, it was like this kind of litany of living beings, as well as supernatural beings. That every being, alive or supernatural, has divinity. And the way he was telling me about it was to start with the names of everything. Love starts with recognition.

Tree:

There was a moment you shared with me that I think epitomises what you’re explaining and that I thought was so moving. I must have messaged you because I was worried you were in Kathmandu when the terrible earthquake happened in April 2015. I didn’t know what had happened to you, or to anybody else that I knew and loved there. I found you somehow, you must have had connection. And you told me what it had been like when the earthquake struck. Can you describe to me the extraordinary scene you described when you went out and found the Newar women pressing their thumbs into the ground. What was happening there? Because it seems to embody exactly what you’re talking about, this profound empathy and love and shared responsibility for the earth.

Coon:

When the earthquake struck, I was interviewing Newar farmers specifically about farming, the old farmers, because so much knowledge has been lost as you pointed out earlier. I was with an 83-year-old woman on the third floor of her wood and mud house in Bhaktapur when the earthquake struck. And we were able to run out, and went to the nearest open space that we could find. There were at least fifty or a hundred other people, mostly Newars, there waiting, because the aftershocks were still shuddering through and it was very scary, buildings were falling on down all around us. I could hear the screams of injured and dying people. Each time, we were alerted to the fact that an aftershock was coming because the crows would start calling and the dogs would start barking and howling. When this happened, the older women would get down onto their knees on the ground and they would press their thumbs into the earth and slowly say, ‘ha, ha, ha ha, ha ha.’

I asked what they were doing. And they told me that they were massaging the earth, they were pressing their thumbs into the earth to say, ‘We’re with you. It’s okay. It’s okay.’ And trying to help bear some of the weight of the Earth’s burden. It was almost as though the earth was trembling, a trembling woman who couldn’t stand up under her load anymore. And the women were showing their solidarity in love with this physical gesture, like a massage gesture or a holding gesture – we’re with you, we’re bearing the weight.

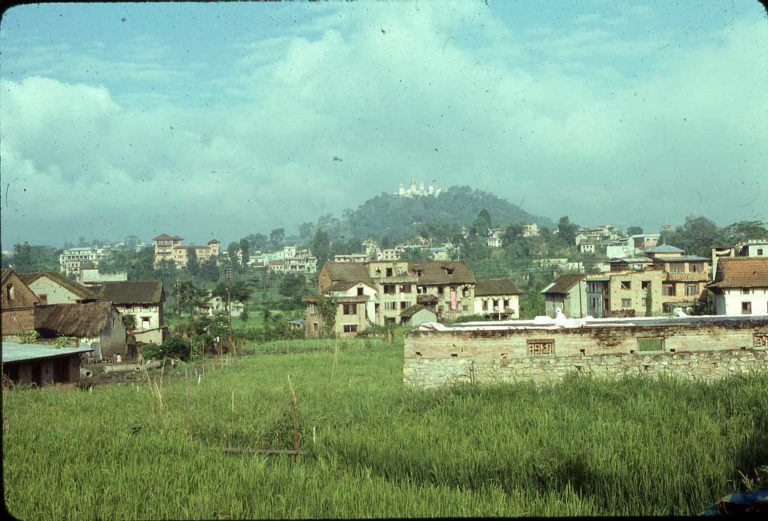

Changa, Nepal © Todd Lewis

Changa, Nepal © Todd Lewis

Tree:

When you say bearing the weight, is there a sense that what human beings have been doing to the earth – polluting it, degrading the environment, even perhaps wars and the way we treat each other – that perhaps we have lost our way? As I understand it, Newars do feel that we are losing our connection with the gods and goddesses, and that spiritual relationship and the lack that selflessness that their culture really embodies. Is that the burden that the earth is feeling? That can precipitate, perhaps an earthquake, in the tantric sense?

Coon:

Yes, that’s exactly right. I mean, one of the Newar religious elders with whom I worked said that the earthquake was a result of human greed and sin. She said that the greed had to do with extracting natural resources, especially water, without reverence, without permission, without sustainability. Human greed and pollution, and forgetting our inter-being with alive, sentient beings, animals but also rivers. We have just been greedily extracting, not sharing, having some people starve when other people get rich, and, and that becomes very heavy for the earth. And these were the reasons for earthquake. These are people who know the science of plate tectonics. They know about that. It’s that ‘and also’.

Tree:

And where are we now? We know that the rivers of the Kathmandu Valley are increasingly polluted and heavy industry is growing apace. There’s unrestricted developments happening across the beautiful and sacred fields and the sacred landscape is being covered in concrete. It’s very dispiriting, isn’t it? Literally, when you see what’s happening to the Kathmandu Valley.

How, how are Newars responding to this, do you think? How do they live when something that must matter so much is being devastated?

Coon:

Last summer, Newar farmers in the village of Khokana fought with armed police in a struggle to stop the government from taking over their fields and sacred grounds, without their permission, for some questionable development schemes – including a highway and a bus park. They were actually threatened for the act of planting rice seedlings in their own fields. But I think that is a question that could really apply to all of us, right? How do we live with the grief of planetary destruction and species and habitat loss? It’s an important question. The Kathmandu Valley is now one of the most polluted places in Asia, which is just apocalyptic: air pollution, water pollution, fertile soil paved over with concrete, as you said.

Tree:

And so quickly, considering what it was like before.

Coon:

In my lifetime. What older Newars who I’ve talked to have said is that it’s important to remember. When I hear the word ‘remember’, I think of cultural historians. I’ve done oral histories with older Newars, and speaking with them I want to know what it was like to sustainably produce food, or a surplus of food, without harming the land or without inputs. But this older generation says, what is important to remember is all the other beings, it’s important to remember our obligations to them.

And just as we’ve created a kind of hell on earth, it’s actually within our power to create heaven again very quickly. But it starts in our minds and hearts. We’re not all going to become tantric Buddhists, but I think that we can start thinking about a sentient world, start thinking about the fact that there are many other beings here with us, and start using our imaginations, and our emotions, to imagine and receive the voices of other beings. To start to feel ourselves as interdependent and understand what inter-being is. That we’re not so separate. We’re not so important after all.

Actually, there’s one question that I want to ask you, Izzy, that I think readers would probably really like to have answered, to do with your last book The Living Goddess, about the Kumari tradition and Kathmandu’s religious culture, and your more recent book Wilding, for which you’re getting so much well-deserved and timely attention. Could you talk about the connection between those two books?

Tree:

It’s so lovely to know you, Ellen, because you’re one of the very few people who could see the connection. The books might seem diametrically opposed. But I think both seem to be about what we’ve been discussing: a different way of looking at the land.

I go back to that idea of the taboo of ploughing. It’s that deep understanding of what nature is about and how it functions, but experienced and expressed in a very immediate and perhaps even emotional and spiritual way. It’s a difficult thing to talk about when you’re living as we are in a secular, desiccated kind of culture, the material world, the individual cult, you know.

It’s very difficult to talk about these things. It’s more natural when you’re talking about them in Kathmandu. It’s definitely something I feel. It seems to me that it’s all tied up with that idea of how we get back to a way in which the masculine-feminine is back in balance again, and with this deep respect for the earth. I think it’s no coincidence that our words humanity and humble, and even human, are connected with ‘humus’. And I think that’s something that that Newars instinctively understand.

Coon:

That’s wonderful. I’ll just leave you with one last little story about Vasundhara and the fasting ritual to worship the earth. I was watching Vasundhara vrata [a fasting ritual to worship the Earth goddess], one year. (I also participated in the ritual once and found it a lot harder than I realised!) Next to me there was an old farmer with grey braids down her back, with a big pair of cracked horn-rimmed glasses. And I said to her, why do we perform Vasundhara vrata? And she looked at me quizzically, as Newars often do, and she said, ‘For our body. For the health of our body.’ I said, ‘I thought it was for the earth?’ And she said, ‘What’s the difference?’ The earth is your body. Your body is the earth. There is no your-body without the earth. And your body is part of the earth. However obvious that seems, it hadn’t been so obvious to me.

The post In Conversation appeared first on Granta.