We never had any time. I paced the island cabin in the Pacific Northwest where we’d been overwintering, denning up like wolves. We’d left everything – LA bungalow, wilting jobs. Here our water came from a well and our power from the sun, though the January sky was a concrete pancake and we had to ration our generator gas daily to make up for the lack of light. Me, L., our kid, what would happen to us? We were weeks away from living with my parents.

‘I got an interview,’ I said to L., through the semi-darkness. We brushed by each other at the propane stove. The cube steak was gristly, how did you cook this stuff?

‘Bingo,’ she said.

Suddenly I was Arthur, freely pulling swords from the stone. I bent back into the cast iron pan. Our lives were ballooning forward, this shining, yawning, kismet-like chance — Excalibur!

Over the bad satellite phone connection, our astrologer friend had handed me this exact Pendragonic visualization. ‘Help,’ I’d said, calling her even before I told L. the news. I was terrified.

‘The task will feel easy, fated, like Arthur’s, almost effortless!’ my astrologer friend said – ‘or else it won’t.’

Voraciously I’d glommed onto the role play, repeating the image on loop as I wadded a waterproof bag with chosen clothes.

In my most utopic imagining, my back was a slab of muscle (even though Arthur sprang Excalibur with his pinky) and the next morning, as the chartered boat ripped away from the beach and my small waving unit (who stood there miming a cheering motion for my benefit and thus – bolstering me and my chance of success – the benefit of everyone involved) I again and again swept my arms overhead to grip the sword handle. I was him, King Arthur, you could also call me Wart. At forty-one I was already dented, a mostly lost cause, but finally the heaviness between my shoulder blades was on its way to being earned and as gelid water slushed crossways in front of us – a hero’s journey – this gave me hope.

*

Twice a month I poked a small syringe of testosterone cypionate at a 45-degree angle into my belly fat, each time on the flip side of my torso. T was thick and needed a draw needle. I was always in a rush, jamming in the point after rapidly priming it. I clunked away the bubbles in the syringe nose and released. It was 40 mgs, mini-stings, basically nothing. A male mosquito might have more. It didn’t make me angry or different in any way I could tell except I was mildly, milkily horny for most of each month and what sleep I did have was drenched in something small and barely familiar, but sex-like, such that I hated waking up.

I was preoccupied with a single fear: that I’d smell different or I already smelled different, and I tried to keep my body from rubbing things, leaving any kind of residue or moldy funk. Often I crept to bed late and kept myself firmly rolled in a foot-wide lane of sheeting throughout the night. In the mornings I’d jump out first thing to help our waking kid and relight the cashed fire. Then while they cuddled, I checked my pits and boxers for something telltale or off. I desperately wanted some kind of animal intimacy and to be invited back towards innernesses L. kept sealed from me – places I used to feel at home in, but now could barely—

The gap kept expanding. I sweated to reach my hand across the outspreading bed. Night gnawing = endless. Wasn’t there some math about approaching zero, but never getting there, never touching?

Other fears: wading partway into twilight puberty, taking myself seriously, being seen. I kept the single-use vials hidden in a beat-up cardboard box on a shelf behind my T-shirts. Ostensibly this was because the accompanying syringes were dangerous to three-year-olds, but more likely I craved some kind of cover, preferably a long low endless cave. Ever since childhood I’d hoped to crawl back into this or that corner and fix myself, then emerge somehow impenetrable, whole.

*

‘Bye!’ I yelled over the blasting duel-marine engines. Then stared across the gray strait. Bald eagles, humongous, shitty, regal, doodled each other dramatically over the green frothy fir tops. This is how it finally starts, I said. I hadn’t been alone in months and months. Feet, knees, chest – I had them. I saw a band of light spasm across the water and looked for an effulgent, rising sword. Soon the boat was packed with businessmen, engineers and project managers in overly-tidy Realtree caps with arms full of plans for the outer islands and how they might develop them. I was also busy! and from the farthest bench seat I remembered where I was headed and shouted into my phone memos and scraps of ideas that might collect into something meaningful, like a job talk, making sure I was heard.

An hour later I was in a barber’s chair in a rural strip mall. From under my smock I stared across the U-shaped parking lot: the Laundr-o-Park was packed, the ubiquitous teriyaki takeout bright against rows of mud-splatted rape trucks. I was copiously bleeding everywhere but into the silicone sheath of my trademarked Diva cup. Years in, I was still bad at Diva cup. Or did I have more blood now, somehow? My pores were getting thicker (also my eyelashes, my genitals), facts I was mostly ambivalent to or confused by, despite all the aiding and abetting I was doing. My strongest, most prevailing sense was that my brain should ignore whatever my hands (metaphorical or literal) were manufacturing, especially with regard to my body and its parts.

In the urinal I shoveled as much blood as I could over to the sink. My legs felt wave-sawn, as if I was trying to hold the floor together with my feet. I was coming from outside to inside. The wind was still whapping, my face was forever red, the tightly-synthetic atmosphere drummed. These slick, beige walls, cocooned from the barbers’ chairs and the parking lot and surrounding potato and grain fields = possibly, at least since birth, the most inside I’d ever been. I breathed in. Tried to condense. Condensing was hard. Everything was foggy, my new glasses prescription was badly off, I often tripped or tried to climb over cat-sized shapes on the January-sodden bracken-deranged paths, cats that dematerialized when I looked back for them. Plus I was constantly drunk from androgen-producing herbs suspended in something akin to Everclear, which I gulped three times a day as instructed by an herbologist I’d entrusted with my monthly finances but never met. He lived in a dusty oaky CA mountain town and his name was Joshua. Believe you bro!

I checked the fade in the mirror as I tried to scrub the bathroom of my leftover bio goop. Fade line passable, at least last-minute interview worthy. My barber was def. gay, which haircut-wise could have been ideal but hadn’t panned out. Evidently not a born-to-fade gay. ‘Gay’ was hilarious though. We (‘gays’) all knew it. In LA we used to go to a lesbian feminist haunted house called Killjoy’s Kastle. Lesbians were the funniest. Didn’t they have someone reaching out of a stall door, also with a Diva cup!, full of thick dripping cornstarch-y blood? Someone with a plaintive voice demanding: ‘WHOOOOO can help me with this?’ F-ing fall out of your chair funny, or your pants, or your life. I splashed some water. Mirrors were also a problem. My face, not the glass, was blurry. I had no idea what I really looked like besides lumpy, fuzzy, profuse. My lip hair draped out over my lips. Trimming it meant committing to ‘mustache’. Not the virile teenage Outsiders kind that everyone wanted either. But tomorrow I had to present myself, offer, among other things, a paper finally proving what everything in my life had been prepping for, building towards, forever. ‘Hey, thanks for . . .’ I said, trying to force a few trial words out, but someone was pounding their body into the urinal’s hollow-core door.

Once, as we sat eating soup together, a writer I loved had said that just the feeling of his breath touching the microphone-weave made him cry. He was the most tender writer I knew and he wrote about drinking and drugging almost exclusively and nothing else. What was more tender than disappearing?

More muffled door scraping.

I exited by way of ushering the guy in with my body, offering him the nugatory bathroom.

‘What’s nugatory mean?’ he said.

‘SMALL, (insignificant, worthless).’ I often used my body this way, to get closer to things. ‘There’s been a murder in here,’ I said, slushing some of the bloody paper towels over towards the trash with my foot. ‘Possibly.’

*

Pre-security, at the nugatory commuter airport, I forwent liquor for cold tea. What could I possibly say to them, the even now amassing committee, that was worth saying? I searched my life for anything extreme. I might talk about the Arctic, though what about it? I was no longer sure. The only thing I remembered about the place was the non-hyperbolic feeling that my head was going to whirl off.

I texted L., who had already won and escaped jobs just like this. I had to check in, I was still a parent despite all this freedom.

There’s a problem, I tapped. I’m writing the same fucking story, all the time, same story, it never changes.

Try the thing about overwintering? she tapped back. We were a team.

Or was it: Alone in a leather chair eating a club sandwich. Sounds tough

?

I was having a hard time interpreting texts. I could feel the text under the text – pale, lethal, struggling to breathe and be recognized. I could hold it – that was the problem.

Overwintering’s not a thing, I texted back.

But of course it was. Overwintering was the only thing. Sticking yourself somewhere for months, in the dark. In the Arctic, trappers’ cabins the size of refrigerator boxes dotted the ice and rock. I opened my toilet bag and from it poured a slug of herbs into my iced tea. They tasted weedy, like they’d been dredged from some over-ethanoled backwoods pump. Plus huge nasty raccoon piss. Gassy, greasy, sploogy. The herbs made me really go for it. Made me feel like I was Mad Max driving a motorcycle for the first time with the accelerator cemented to my tongue and also with half my brain already shorn off, drooling.

Our kid called me ‘papi’, which I loved. It was a substitution but not. A marker of difference, right out in the open. Something anyone could feel okay using, even if to us it meant all kinds of semi-subcultural things. Rubbings we invented or turned up. But now, even we (degreed, invested in undoing paradigms) had become confused by it. By subbing ‘papi’ in for ‘daddy’ and ‘father bear, cat, etc. etc.’ every single time it came up in a book or conversation, didn’t it take on the same patriarchal dadcore valence?

I was too sensitive. This was a known quantity in all my relationships. All of my girlfriends, partners, wives told me to ‘stay on my own side’, as if that was a possible maneuver, something I had chosen not to do but had access to, like email correspondence, like getting this job with health insurance. I wanted to stay on my own side. Wanted to erase the presensing, uncomfortable ability I had to mold myself to others’ perceived needs, or when I saw someone reacting, to favorably overcorrect. Maybe the T would help, I often thought, at least before starting it. Not because I’d be less female, but just because I’d be less ‘me’.

I boarded the plane last and slumped into the aisle seat, nodding and slobbery from the sediment at the bottom of my herbs. Had that been me in the security line, chugging the sludgy many-dose bottle so no gloved hand could snatch it? The Arthurian power was still in me somewhere. I had less than twelve hours to produce. I ripped open my laptop, my hands felt clumsy, this was another effect of T, I’d read. Your finger pads might change.

OVERWINTERING:

I pounded out.

I’d recently noticed the keys on my dad’s laptop were completely worn off from the acids in his fingers and the velocity at which he struck them. He’d replaced them with huge neon-yellow letters so that the whole keyboard was shouting at him. Ear hair, elongating nose. Would that happen to me?

But after OVERWINTERING I couldn’t get anything going. I knew writing should be completely unrestrained, more than was otherwise possible. Like anything, a story was a body.

In the talk, I wanted to explain two basic things about being in Svalbard, on the island of Spitzbergen, very near the North Pole, two things besides what mattered most: that L. was pregnant and I was very far away.

The first was something the trip leader had told me. She was enigmatic, always in a huge parka or else swimming naked, i.e. enclosed. ‘I needed to be lost,’ she’d said. ‘So I told him to blindfold me and take me somewhere on a snowmobile, then dump me off.’ Following these instructions, she said, he left her in an unmarked trapper’s cabin for two weeks, or maybe a month, before his need to retrieve her overpowered him. He’d done exactly what she’d wanted, but they never recovered from it, sexually or otherwise. ‘We had to break up,’ she said.

The second was an even more vapory story about a baby born into a barren, snow-pasted fjord hundreds of miles from the nearest clinic, whose mother couldn’t make milk. The parents found a seal, the trip leader said. And when the ice disappeared with the spring melt, the baby weighed more than a three-year-old.

Now I wanted to go back there. This was, among other things, what the ‘talk’ was about.

I also knew that I needed my family to come. Three months in the darkest place on earth seemed urgent. Our main problem was sleep. Now that we were finally getting some, it wasn’t rejuvenating us.

Even just last night L. had punched me in the throat while dreaming. You punched me in the throat! I said, bragging, wanting her to apologize. It had almost felt good, and in this morning’s cold-padded air I tried to show her the bruise.

‘There’s nothing,’ she said.

But there was something! Fresh neck wrinkles, I’d just discovered them. Time was screaming, soon the tangy wild roses would be out we’d never have a second to look at them, our kid would be gone, I’d be an old maybe-man, we had to take it seriously.

‘Plus how about compassion?’ she yell-whispered, trying not to wake him, our kid. ‘It was MY nightmare, you never even asked me how I was.’

My laptop screen blinked, still morbidly empty of meaning. My body was pulsing and woozy. Gross, how could I possibly be turned on now? But whenever the feeling showed up, I was relieved. The plane wobbled as it descended through the stratocumulus layer. No job talk meant no magic bullet to save us, no tidily-creased benefits package, no ego fuel, no proof I was okay and somehow legible, i.e. could continue being.

What, anyway, was reasonable? One summer I made all my money pulling the single digestive vein out of shrimp after millionth shrimp, de-heading them alive with a pop of my thumb.

‘I dreamed,’ L. said, another mostly sleepless night, ‘that nothing should enter you.’ Which was in itself an opening back towards her.

‘Yeah,’ I said, lunging for it. She was right, I didn’t want anything to enter me. Except, wasn’t I begging for entrances all the time? Maybe it didn’t matter anymore and I was ready to accept the universe’s pupae, the soft, spasmodic love I was always saying I was desperate for, i.e. if nothing came in – breath, serum, sophomoric libido, sex, everything that was fluent and charged up with meaning – how could I ever change?

We’d fought about all of this but it didn’t mean anything, it was just a fight about fear.

‘WHOOOOO can help me with this?’ I said loudly to the flight attendant, trying to hand him my laptop screen.

I was always sure someone could do a better job of my life than I could. I turned towards my seatmate in 26D, who must have worked for VSCO or Tinder. We were landing in the ‘Bro’ Area after all.

‘Remember King Arthur?’ I said. I did a quick, gestural sword pull.

‘Uh,’ he said.

Something in him = annoyingly squirmy. I did it again, lingering for effect as I drew the blade, no small feat in economy. Lancelot had been in love with Arthur, had it for him hard, the squishy weight of something dick-like, the pulling it out metaphor, hadn’t I cried into, become gay into that book? I could also pull it out!

‘Uh, so I think that’s He-Man?’ he said, wriggling more. ‘You know, “I have the power”?’

Landings always made me tear up, it was the air pressure. I turned away, toeing a cracker out of the aisle with gusto.

*

That first late October in the Arctic, when I’d disembarked the runway airstairs, most of the world was below me, almost gone. It was morning, but the sun’s face was missing and the sky was obsidian-lite. As we crossed the tarmac I saw a lone goose in the nearby tundra. See, something was living, thriving.

I texted L.: made it! Instantly the text landed in LA. Satellite-globs make connectivity lighting-quick at the poles.

Then came a series of endless nights or endless days. My phone and computer barely worked due to the cold. The darker it got, the less I slept, the more unaccountably amped I became.

‘But how did S. know when to come get you?’ I asked the trip leader, an artist, after she told me her story. We were with the group in the settlement’s sole and unclosing bar. For the first time in my life drinking beer was unnecessary, the buzz was already so high. ‘Like, how did he know you were alive, let alone done being lost?’ I was jealous of the dynamic, recognized it.

S. was at the next table over, body huge and capable. His name meant something like ‘mug’. Of course he was aware of her entirely.

‘But I wasn’t done,’ she said.

Across the road, above the Svalbardbutikken Co-op and rows of now-dogless husky chains, sheets of tinfoil sealed an apartment’s windows against any past or coming light. Soon a group of us would leave the bar, find the apartment’s owner, force him to surrender his last bottles of wine, claw down the foil . . .

I’m at the top of the world! I said to myself, laughing or howling inside. I was, without knowing it yet, also there to evacuate something. To take out the ‘I’. I had to stamp myself down. How else could we survive?

I was walking over very loose gravel.

‘WTF, we have a kid coming?’ L. could have said. When I tried to tell her about all the weird hour-by-hour yo-yos in polar darkness, how dawn never came, though continuously drinking we stayed up past nine a.m. – were still awake – watching for it.

*

I wanted I gone but couldn’t stop talking about myself. But it’s so gooey! Recessed, hidden, stuck. If I opened up my throat, could anyone (dedicated, head-lamped) ever get to it? The Arctic was falling apart, leaving its own exposed, sloppy trail. It made me think of Lygia Clark’s Baba Antropofágica with all that spit and all that saliva-soaked thread, Lygia who said: ‘I dreamt that I opened my mouth and took out a substance incessantly. . .’

The next day in the big conference room on the California coast they would ask me about her quote, how one minute I translated the work as: ‘Cannibalistic Slobber’, and another time: ‘Cannibalistic Drool’.

‘Don’t you care?’ they said.

What was the difference between those two self-slicking words? The quality, the momentum of the wanting? How bad you needed it, far you’d bend?

‘I’m trying to stretch language to fit my body,’ I tried to say, or meant to.

And if there’s no cave dark enough?

But that was tomorrow and now I was still on the generous ocean-view balcony with my laptop, my thighs half-frozen, half-thawed. Below me, hoarse, possibly restorative pinniped sounds bonked chorally. What was seal milk (besides thick, creamy, exponential), what did seals do. I needed to slow myself down or I’d be non-interviewable by morning. Behind me the big, loose, quiet bed. If only I could show the bed to L., if only we could lie there next to each other. Everything was possible about our life except we weren’t healed yet, which meant when we were done overwintering, we might, like late ice, break up.

‘To combat fear,’ our therapist said, ‘the brain stem needs small sentences, no personal pronouns.’

I stared at the bruise-blue Pacific – impassive, rapidly swelling without remorse.

‘It is night, it is safe,’ the therapist intoned over Skype, audibly demonstrating. She meant we should use it for our kid, but he slept fine. It was us, our problem.

Behind me, the salt-grimed sliding door: ‘It is night, it is safe. Sleep is here, sleep can come.’

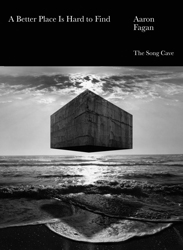

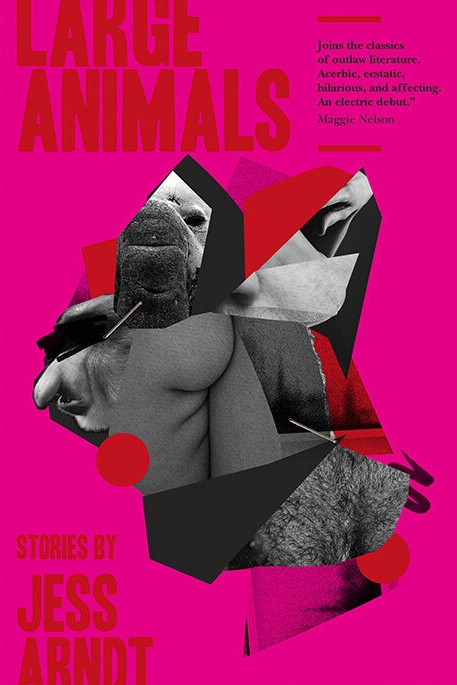

Jess Arndt’s short story collection Large Animals is available now from Cipher Press.

Jess Arndt’s short story collection Large Animals is available now from Cipher Press.

Image © Ingrid Siegel

The post Slobber and Drool appeared first on Granta.