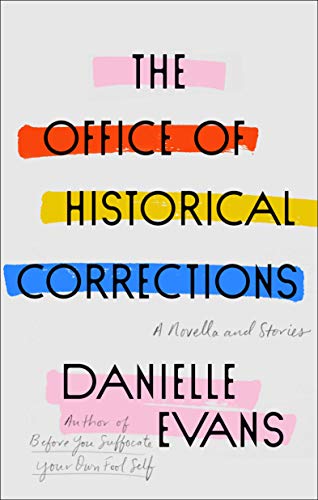

Short stories are a complex form, one that author and professor Danielle Evans continues to show herself adept in. The ever-shifting opportunities of short fiction are evident in Evans’s work, from her debut collection Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self to her latest, The Office of Historical Corrections. The titular piece is a novella about a fictional office, the Institute for Public History, where we follow a field agent meant to correct a “contemporary crisis of truth” in America. In “Why Won’t Women Just Say What They Want,” a master manipulator attempts to make amends to the women in his life, though this attempt comes into question. In “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” Dori’s awkward invite to an equally awkward bridal shower exposes a bond in grief, and Best American Short Story 2018 entry “Boys Go to Jupiter” reflects the balance and backdrop of Claire’s decisions, her own evasive tendencies and the consequences. Everything is complicated in Historical Corrections, and by unraveling these complications through her characters, voice, and environment, Evans offers commentary on our daily life that isn’t just topical but eternally relevant.

Danielle Evans and I spoke about her approach to the short story and teaching, the prevalence of questions that abound in her fiction, and how the true story, no matter the length, unveils itself in revision.

Jennifer Baker: When I read this collection I thought “Race is definitely part of these stories and there’s so much more that Danielle is presenting that makes me realize how messed up we are as people.” Evasion sticks out to me especially now that we’ve been quarantined with ourselves and haven’t had to look at themselves very deeply before. Were you thinking about those connective threads even though these are all stand-alone pieces?

Danielle Evans: I think my craft obsession is that gulf between what we think we’re saying and what we’re actually saying, or who we think we are and who we actually are. And that is something I come back to again and again both for context and for characterization. Because I think most possibility for narrative happens in that space. The space between how we feel and what we say, or who we thought we were and who we actually were when we had to make a choice makes narrative surprise possible. It makes writing these characters possible; it makes it possible for these characters to do something you didn’t expect them to do, but still feels in character and doesn’t break the mold of the story. And so a lot of the characterization is in that space, that sense of having sometimes a very self-aware performance that becomes second nature until something kind of calls it into question. (Like a long quarantine, perhaps). And it is related for me to those structural questions, though not exactly didactically determined by them, because I think the more of a sense of double consciousness or external gaze or other people’s expectations you have to navigate the world with, the more conscious you are of the gulf between what you would like to say and what you have to say if you would like to keep your health insurance, or what you’d like to say and what is safe for you to say and what will cause you harm if you say it.

Because I’m writing Black women most of the time, I’m writing people who are very conscious of the stakes of not seeming in control or not meeting people’s expectations of them. Some of them react to that thinking [those expectations are] about respectability, and some of them react to that by understanding respectability is impossible.

Jennifer: Related to that question of who we think we are is the story “Boys Go to Jupiter.” A version of it was published in 2017 with The Sewanee Review. I don’t know if you wrote this story post-2016 election or if it kind of formulated over time?

Danielle: Actually, I wrote that story in 2013, and I hung onto it for a while in part because I wasn’t supposed to be writing any short stories. I first got kind of mixed notes [on it], some people were excited about it, but I didn’t really have the energy to do a good revision of it at the time because I was working on this other thing. So, I put it in a drawer. I finished it finished it in… I guess it would’ve been early 2017.

Because I’m writing Black women most of the time, I’m writing people who are very conscious of the stakes of not seeming in control.

The thing that changed between those early drafts and later drafts was mostly me trying to find a way to get more Aaron on the page. Because it is a story that’s about evasiveness. It is a story about a character who doesn’t want to be accountable or look at her own past or anything that she’s done. It’s a story about, partly out of grief and partly out of privilege, this person whose entire world is evasion and this is one of those things she really didn’t want to look at. And it was like, how could I get the scenes in this story so that Aaron feels like a person, which is important, when she’s not looking at him at this point like a person, or she’s not actually looking at the stakes of the situation or learning from it. All the work I did on it after 2014 was really scene-level work trying to think about how to let the Black characters in the story exist around this person who didn’t want to see them. So that you had the narrator, but you had something putting pressure on her version of the story.

Jennifer: How hard is that for you to figure out? Especially when you are considering the Black characters and not trying to implement a solitary focus of who the narrator is and their journey. You’re also thinking about the secondary and tertiary characters who matter so much to the story.

Danielle: At one point I said, my third book is going to be a novel that takes place on campus, and I had this idea that there’d be four primary characters who would have their own section and Claire would be one of them. And then when I started writing it felt like a short story to me immediately. It felt like I could do the work in a short story space. In part, I felt like I could do the work because I realized that a lot of what I wanted to do with those other voices was to offset Claire. It’s a story that really belongs to Claire, and in some ways it would be problematic to have other characters come in to say, “oh she’s missing this” instead of inhabiting their own stories, to be secondary characters in her story for the sole sake of saying “oh but she’s wrong about this.”

I also felt there were ways in which [Claire] could obviously be wrong about things or obviously be missing things that I didn’t need to tell the reader. But if the reader wasn’t going to get to the end of the story and think “this is a story about a villain who doesn’t think she’s the villain” then there’s nothing I could’ve written for that reader. And it wasn’t my intention to try. What was important to me was that these characters put some pressure on her narrative by creating space for the omissions, but also feel like they didn’t just exist for that. That they were people off the page beyond what Claire was able to see from her own point of view. Trying to stick that into the story was a challenge because I felt like if I gave too much room to them I’m giving too much credit to Claire, but if I’m not giving enough room to them then they’re just there as footnotes to say “oh this person is unreliable.” I had to find enough room for that confusion to make the narrative go beyond what Claire understands.

Jennifer: You mention seeing “Boys Go to Jupiter” as a short story and feeling that you could do this in the short form. And that you were attempting to write a novel. When it comes to recognizing form it sounds like you think very analytically. So I’m curious about your process.

Danielle: I try to write a first draft as quickly as possible and take as much time as I need to revise. Because what I’m trying to figure out in the first draft is where the layers of the story are.

I think, yes, the short story is a compact thing in some ways. For me, the pleasure of the short story form is to think about where all of the components of the story are coming at once. The story can be focused on a particular moment, but it can also move into the past and future as needed. And often when you get to a part in the story where the past, present, and future come together on the page in some way, that’s when you find out what the story is actually trying to do. And I like that compression, I like that intensity. I don’t think too hard about a first draft at all. But I do immediately on a second read start to ask what are the operating questions of this story, what are the operating intents of this story, and where do they come together on the page?

I very much dread when somebody asks me to try to answer the question of how to be antiracist.

Jennifer: You said you didn’t intend for it to go where it went and maybe it’s an unanswerable question of how you got there.

Danielle: There was a big rewrite between the first draft and the second draft. I figured out “oh this is where this is going, okay” and then to retool it to make it match the ending, which did feel like the right ending to me. But I felt like I hadn’t necessarily in the beginning set that up. And so, I wanted it to feel like you didn’t see it coming, but also that the story was unwinding, from the view of this character who feels various layers of guilt or evasion about what’s happened. But yeah, it’s interesting to think about it in the context of antiracist reading. This book was in ARCs late last year and I swear if it hadn’t already been in galleys when we were having the public conversation about Juneteenth, I probably would have changed the scene that references it. I was like, “Oh my god! Everyone is going to think I was trying to immediately write about topical things!” But the book was in galleys, so it was too late, people had already read it. The reference was there to mark that the story was set in some kind of alternate future, where Juneteenth was gentrified, and I just ended up writing about the present. Writing is a long process and in some ways always anticipating the future conversation, but of course you can’t actually predict the future or the exact world or conversation your book will be released into.

Obviously racism was very much on my mind when I was writing these stories. But I also very much dread when somebody asks me to try to answer the question of how to be antiracist. You never want to be the reasonable negro in someone’s organization and you never want to be the unreasonable negro in someone’s organization. They’re both impossible positions.

The post Stories Happen in the Space Between How We Feel and What We Say appeared first on Electric Literature.