Even if you’ve read Jack London, you might not know Martin Eden; whereas outdoors adventures The Call of the Wild and White Fang are frequently assigned in schools, the semi-autobiographical story of romance and writing is less well-known. The 2019 film adaptation by Italian director Pietro Marcello, released in the U.S. this October, may not move the needle too much—it’s a small release, with mixed reviews. But what’s really interesting about Martin Eden isn’t the story in the book or in the movie. It’s the story behind the story.

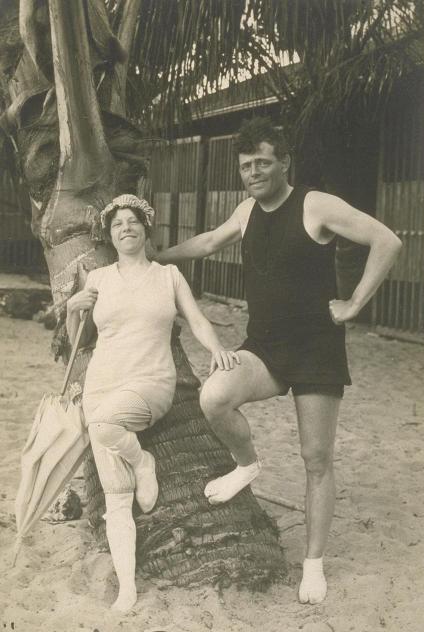

London wrote Martin Eden (originally titled Success) during a voyage he and his wife, Charmian Kittredge London, took through the South Seas on a small yacht called the Snark. Charmian had given Jack the idea for the journey, one she had seen enacted by Joshua Slocum in his book about his own journey, Sailing Alone Around the World. She read Slocum’s book when it came out in 1900 and then saw the author speak at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. When she and Jack started their affair, while he was still married to his first wife, the idea of this nautical journey around the world together was one of the shared interests that brought them together.

Martin Eden focuses on a former sailor’s quest to find a better life through the pursuit of knowledge and art. Many scholars have observed that the text is somewhat autobiographical, but unlike the solitary Eden, who struggles with isolation from both his working-class background and the society he attempts to fit into, London was anything but a solo artist. Beginning with his 1904 novel The Sea-Wolf, London relied on Charmian to edit, type and sometimes even ghost-write parts of his famous novels. Martin Eden was no exception. Jack and Charmian began working on the novel while taking a break from their expected seven-year journey around the world, stopping to repair their boat in Honolulu in the summer of 1907, and Jack finished writing the novel in Tahiti in February of 1908.

Marcello’s film emphasizes the androcentric lens. A young seaman who dreams of more for his life is transformed into an intellectually curious creature via his love for an upper-class woman, Elena (changed from Ruth in the novel). In Marcello’s telling, Elena and all of the other women who play opposite Martin are mere cardboard cutouts: flat and without growth. Martin (using their bodies, or minds) propels himself into a successful career as a bestselling author. When he meets his success, though, Martin finds it distasteful. He turns away from it—and from Elena, who comes back to him—because he feels that she, and the world around her, lack authenticity. Instead, the movie ends with a scene reminiscent of London’s ending. Except, instead of Eden jumping into the sea from a steamer bound for a new life in the South Seas, Marcell’s Eden just walks into the sea to his death.

Both the movie and the book begin with a vision of a better life. Martin is fascinated by a painting of the sea he sees inside of Elena/Ruth’s eloquent home. He’s fascinated by how from far away the sea, and the boat within it, are beautiful, but up close they are just “careless dabs of paint.” To Martin, the idea that the painting’s beauty was only a trick was puzzling, foreshadowing the disillusionment he will have when he looks more closely at Elena and the others of her class and finds their beauty and wisdom disappears..

We can experience something similar by taking an up-close look at Jack London’s life. From far away, London was an individual genius writer. But up close, the ugly truth, the brushstrokes, that made that illusion so beautiful from afar are fully visible. Each adventure London sought and experienced, each book he wrote was aided by another force of nature: his second wife, Charmian Kittredge London.

Each book London wrote was aided by another force of nature: his second wife, Charmian Kittredge London.

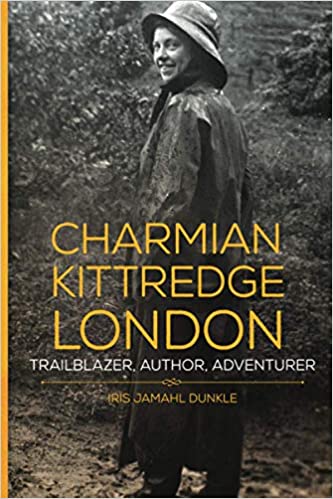

When I was in the sixth grade, I visited Jack London State Park in Glen Ellen, CA on a field trip. Prior to this, I’d spent most of my childhood writing stories; however, I had no idea that one could actually become a writer. I had never even met a writer until the day I walked into the museum at the House of Happy Walls at Jack London State Park. Suddenly, walking through the exhibits, I saw you could spend your life traveling the world and writing about it. I fell instantly in love with Jack London and vowed to read everything he had ever written. What I didn’t know, though—and didn’t find out for decades—is that the house I’d visited that day belonged not to one writer, but two. Charmian Kittredge London, Jack London’s wife, was a writer, an adventurer, and the reason why this museum and park even existed, but when I walked through the museum, her story was not told. This idea of a woman’s life being devalued, or in Charmian’s case, eclipsed by her husband’s life, is all too familiar, especially in the literary world. And it is why I’ve spent the last six years of my life digging up the forgotten life of Charmian Kittredge London.

Before they left on their long anticipated Snark journey the public was shocked that Charmian was not just going to be a passenger, but an actual member of the crew. The San Francisco Chronicle described her “In bloomer will tread the deck—Young woman to bear her share of navigating vessel during 7 years’ cruise.” Although Charmian thought nothing of signing on as an able-bodied sailor, the idea of a woman disobeying gender norms caused several “concerned” citizens to write to Jack about their apprehension for Charmian’s health. She later remembered one of these letters: “I am minded of the solicitous old sea dog who warned Jack letter that it was not safe to take a woman outside the Golden Gate in a boat of the Snark’s size; that we would be bruised over our ‘entire person’ unless the boat be padded.”

It was on the Snark journey that Charmian came into her own as a writer. On the trip she’d begin to write three of the four books she’d publish during her lifetime: The Log of the Snark, Our Hawaii and Our Hawaii: Islands and Islanders. As she wrote to her aunt while traveling on the first leg of the journey from San Francisco to Hawaii,

I seem to be coming into my own…Without office life to vex & distract, my life is all education–the very living of it is such, & the work I do for Jack, is practical education, is practical education; there’s no let-up. Wouldn’t it be fine to go on writing? Perhaps I shall.

The thought of not only creating but publishing a book thrilled her. The public, the press and even Jack’s friends had been hard on Charmian since she married Jack and his oversized personality left her little room for her to be herself. But on the Snark, all changed.

Over the next three years, Charmian would write every day about what they saw and experienced traveling from island to island on the Snark. But many of the extraordinary experiences she had, especially those that challenged gender norms, were excluded from her husband’s retelling of their adventures. For example, when Jack and Charmian spent a day surfing in Waikiki, Charmian was proud to catch a wave several times. So was Jack. When he wrote about his experiences surfing in the essay “A Royal Sport,” he failed to mention that his wife had successfully mastered a run or two. It was an omission that would recur throughout Jack’s account of the trip. Charmian understood that Jack’s brand was adventure. The more daring and interesting he appeared in his episode about their trip the more copies he would sell. And his feat of surfing on a ten-foot wooden surfboard would not have looked so adventurous if his small, fit wife had also accomplished the same thing.

They would visit seven major islands: Hawaii, the Marquesas Islands, Tahiti, Bora Bora, Fiji, Samoa, and the Solomon Islands, before their adventure ended abruptly in Sydney, Australia, because Jack developed a strange and troubling sickness. Charmian based her own writing on Joshua Slocum’s Sailing Alone Around the World, writing chronologically in a daily log that captured not only Jack’s adventures but her own. Writing the Log of the Snark shifted something in her and by the end of the journey Charmian saw herself as a writer. It was after their return from this journey, buoyed by this new found confidence, that Charmian began to provide even more input into her husband’s writing.

Had Charmian fully come into her own as writer before Jack began discussing and writing Martin Eden with her, she would likely have had more of her influence in it. Ruth (and subsequently Elena in the film adaptation) might have been a more dynamic character. In later years, Charmian would help Jack plan, research and write The Valley of the Moon, in which Saxon, the protagonist, is a strong woman who leads her husband on a quest out of the poverty of inner city life in Oakland to find a better, more meaningful life. But due to Jack’s image as an individual author, and the near-erasure of Charmian’s biography over the past 80 years, the truth of her input was never seen. When it comes to the lives of women, it’s time for us to step closer to the beautiful paintings of male lives and ask: What brush strokes were added by others to make that art?

The post Why Was Jack London’s Wife Written Out of His Legend? appeared first on Electric Literature.

Be First to Comment