The humorist talks about putting together a book proposal, leaving Hallmark for freelance writing, and where she finds her writing ideas.

You’ve probably had enough time in the past seven months to contemplate which parts of our lives are actually really weird and if it quite necessary to continue doing them every day. Why did we drive to the office when we can do our jobs at home? What is the point of putting on outside clothes anymore?

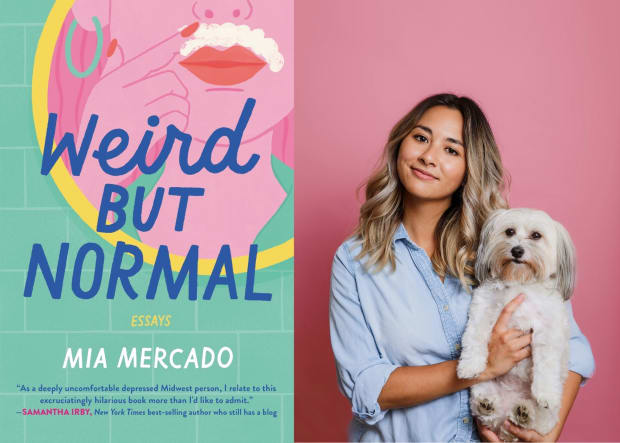

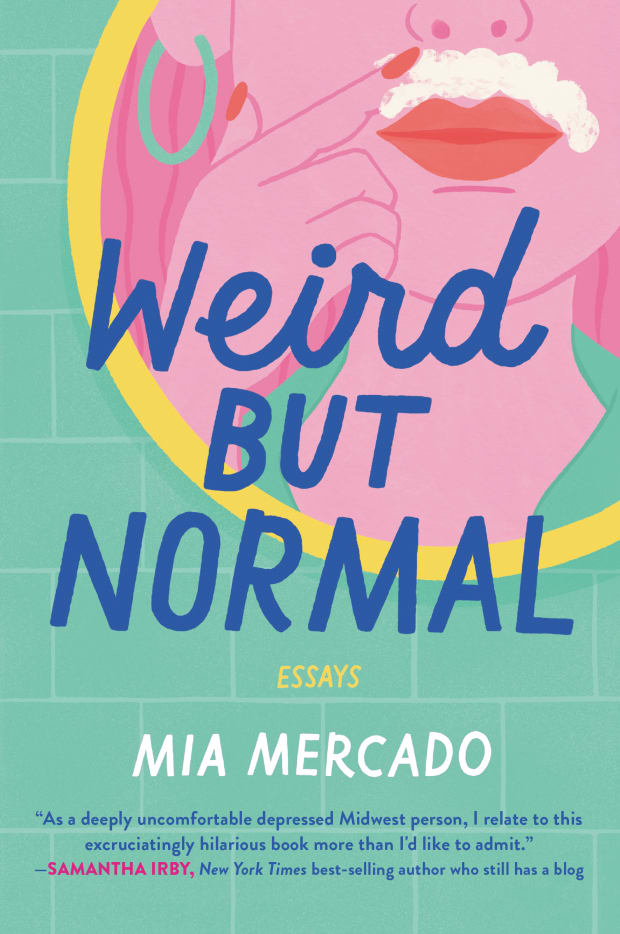

The humor writer Mia Mercado is ahead of her time. She began questioning things that are quite strange but society accepts as normal before the rest of the world shifted—the suburban nonsense of Bath and Body Works, child beauty pageants, Hollywood standards on how women age, etc.—for her collection of essays and satirical pieces Weird But Normal (May 2020, HarperCollins). Mercado’s work also touches on how uncomfortable things most people think are weird are actually very human and normal, such as her personal essays that recount hiding her soiled underwear in a wood pile and once believing that sex involved pressing index fingers together.

Before releasing her debut book into the world, Mercado’s work had been published in The New Yorker’s Shouts and Murmurs, McSweeney’s, New York Magazine’s The Cut, The New York Times, and more. She lives in Kansas City.

In a phone interview with WD, Mercado talked about putting together the proposal for this weird, colorful, gem of a book with literary agent Monica Odom; learning how to write while working for Hallmark and leaving the comfort of a full-time position for freelance writing; and where she finds her writing ideas.

Can you tell me a little bit about what your book proposal process was like?

I signed with a literary agent, Monica Odom, in March of 2018. I had an idea when I first started talking to her that was pretty loose. I knew I wanted to write a collection of funny essays that were both personal essays and some conceptual/humorous/satirical pieces. She helped me shape that into something that made sense and wasn’t just a bunch of things that I think are funny and now they’re in a book. She has a good sense of what publishers are looking for and what is oversaturated.

I knew a thing that was going to be important to me was feeling like I could talk about my experience as someone who is biracial as a female in the Midwest. I wanted to make sure I could talk about all those things at length and not feel like I had to self-censor or ignore them entirely. Some of my initial ideas were like very heavy like, “This is going to be a book about gender and race and that’s it.” And she was like, “That’s great. But I don’t want you to limit yourself.” You can talk about those things under a bigger umbrella, which was a helpful way to think about it. What the book shaped up to be is pretty similar to what the proposal was. This is my first book and I had no idea what a book proposal was.

I understand having to sell the thing before you make the thing, which is always strange where you have to prove that you can write by writing a bunch of stuff that isn’t the thing that you’re writing. So I had this proposal that was like, “Here’s who I am, here’s what I’ve done. Here’s the stuff that I want to write. Here’s the stuff that I have written that’s similar to that. And also here’s a couple of sample chapters, some of which were pieces that had already been published, places that I thought fit into this theme of things about ourselves that we think are strange that are normal, and things about culture that we take as normal that are actually strange, if you take a second look at them.” That idea was really shaped in partnership with Monica Odom.

We shopped it around to a couple of publishers and ended up going with HarperOne. The editor I worked with there, Hilary Swanson, really understood what I wanted to talk about holistically. I think she said she read a line about knowing that a partner isn’t right for you if they have a particular affinity for Dane Cook or some random lines in the book, and I was like, “Yes, this is the one she is going to be my editor wife.” I got lucky and also had good people surrounding me to help me find other people who understood the thing that I wanted to write. We were able to shape it into this thing other people would understand and that makes sense in a book format.

I sold the book to HarperOne in fall of 2018 started writing it in January of 2019 spent most of 2019 writing the book and turned in the final draft in August of 2019. So it’s been a minute since I’ve written the book and like anything else I’ve ever written, I keep having moments of, “What if everything that I wrote makes no sense and isn’t funny, and it’s just garbage from my brain I thought was funny by myself in a coffee shop that no one else is going to get?” It’s very reassuring to know that even though there’s a lot of things that are changing or a lot of things we are talking about right now that we were definitely not talking about as loudly when I was writing the book. I’m glad there are parts of the book that still feel relevant, even though this is an idea that I had years ago.

How long have you been writing pieces toward this book?

I have been freelance writing for five years. Like anybody who got an English degree, I always thought in the back of my brain it would be cool to write a book. But that also sounds like someone being like, “It’d be cool to fly. It’d be cool to go to the moon.” I thought it was just a pipe dream. As I was writing one-off humor pieces for different outlets, I got a better sense of the kind of stuff that I wanted to write and also realized I love doing conceptual humor pieces where I, as the writer, like writing from other people’s points of view, but the stuff that resonates with me the most is personal essays.

There are four or five pieces in the book that had been previously published in places like McSweeney’s or The New Yorker. There’s one piece that was published on The Belladonna, which is one of the first places that I had a piece published. I had these pieces that were not meant to live together, but as I started thinking more seriously about what’s this book is going to be, I was able to pick from those satirical pieces and I had nuggets of ideas from different things that I’d written that were more personal. Definitely nothing that was completely formed.

There are a couple of stories in the book that I’ve written about before, but never at the length I did in this book. And also not with as much thought behind it. It was more just like, “I remember the story and I want to write it down so I don’t forget it. I want to make sure at some point in the future I write about this, but I just gotta write down all the details.” Like the story where I hid my poopy underwear in a wood pile. That was a story I had forgotten about for so long. Then I remembered it while I was still working at Hallmark and was like, “Oh, I did that. That was a real thing that happened. I need to remember I did that because I feel like other people will enjoy it.” So I really only was writing stuff for the book for about six or seven months during the time period right after I got the book contract.

Can you tell me about how you found your agent?

I have been very fortunate to work with a lot of people who have championed my work and understood my voice for a while. A friend of mine and a very talented author and artist, Rachel Ignotofsky, is someone I worked with at Hallmark. She left a couple of years before I did to start writing books. She wrote and illustrated a book called 50 Women in Science. That was a bunch of different short biographies of women with beautifully illustrated accompanying pieces. Monica Odom is also her agent. Rachel was working with her and as I was talking to Rachel after I left Hallmark, I said I want to write bigger things, she was like, “Let me introduce you to Monica.” Which was very gracious of her and is a thing that I’ve been trying to make sure I perpetuate.

I appreciate people that are nice for the sake of being nice and helpful just because they know how helpful it is when other people give your name to somebody as a boost. Monica was kind of familiar with stuff that I had written. She’d read a couple of big pieces. We had an initial phone call and she was like, “What are the kinds of things you want to do?” And I asked her about the kind of projects she’s interested in. From that conversation, we were like, “OK, we both have this other person whose opinion we trust, who can vouch for each of us and the projects we want to work on really meld.”

When I started those initial calls with her, I did have a couple agents reach out to me. That happened after I had a piece published in The New Yorker. That was the first time that I had agents reach out and say, “Hey, I like the stuff that you’re writing. Have you ever thought about writing a book?” Which was exciting, because I want everybody to love me all the time and also like strangers with like fancy job titles sending me emails—the little serotonin that my brain needs all the time.

That was helpful context to see what other agencies are out there. My experience with publishing is limited to this book that I’m doing. Seeing what other agencies were doing, talking to other people who had a similar path as I did, where they published humor pieces and then signed with an agent was helpful. Mostly just to know what kinds of agencies are out there and what different agents do for different people.

The thing that I’m finding is usually bigger opportunities come from somebody who’s already at that space and helping pull people up to that level. That’s a thing that I want to make sure that I’m perpetuating. I want to make sure I am opening the door for other people and other groups who might not otherwise get the opportunity to do the things that they can do very well.

Well, that’s being a good literary citizen.

That’s the motto I’m trying to live by. There’s a lot of things happening right now and it feels silly to talk about a book that is just about me and my experience. But like I said, the things that have helped me understand myself better are when people write about themselves and rather than being like, “Here’s this thing that’s happened. Here’s how you should think about it.”

I get a lot more from somebody talking about an experience, saying how they dealt with it, saying what it was for them, and then giving me the space as a reader to be like, “I can see how that’s similar to things I’ve experienced or seen. What does that mean for me?” It’s hard not to feel personally tied to every part of my job when my job is very personal, sharing parts of myself. I want to make sure I’m doing things in the writing world that I am trying to do as just a human first.

The kind of writing you described is the kind of writing I love to read, so I totally get it. Where do you get your writing ideas from? How do you decide what’s funny and when you should roll with it for a piece?

Man, I wish I had like a scientific explanation for you. I wish I could say “I do this, and then, oh my god, it’s so funny and everyone laughs at it.” It’s a lot of different things.

For conceptual humor pieces, usually those ideas come from things I’m experiencing in real life. The first piece I got published in The New Yorker was called a compiled list of collective nouns—names for different groups of things, like a group of ants is called a colony. That idea came from a time I was driving home from a coffee shop and I saw a group of 20-somethings in business casual clothes, standing outside of what definitely looked like a new coworking space. My brain went, “A group of a group of millennials is called a coworking space!” Then I was like, “Maybe there are more of those. Maybe I could do a whole thing like that.”

Best case scenario, I’m doing a thing and then my brain forms a joke. Usually I notice something and think it’s funny or strange, and I don’t think other people are calling much attention to it. And so trying to frame it in a way that I’m like, “We need to talk about how ridiculous this thing is.” I also have a running notes list that’s half ideas that make no sense and if anybody saw it, they would be concerned.

When I was writing a book proposal, I had days where I was just making lists of different stories that I know I have, or moments of taking inventory of the things I know I can talk about at length. I guess that’s how I come up with ideas is making lists. It feels productive, but also like you’re not actually having to write, which is the hardest part of writing is actually doing it.

So, once you’ve gotten your ideas out and you’re picking ideas from your list, what is your writing process like?

Right now, it’s very different. I have zero routine right now when it comes to writing. But I usually work from home most of the time. I commit the literary center of writing from my bed all the time. I know people say you shouldn’t do that, but it’s comfortable. Isn’t that the dream, to sit in your bed all day and somehow you make money because of it?

When it was still a safe idea to go into public spaces, I would go to coffee shops and mostly rearrange my phone and computer until they closed and pretended to write, made sure nobody was looking over my shoulder and seeing that I’ve been sitting in the same spot for five hours and haven’t written anything. Because I live in Kansas City, I have a car and I can drive places and it’s a relaxing thing for me. Probably not a great thing for the environment—sorry environment, but driving around is my muse. If I was ever feeling stuck, I just drove around a bit. I am not somebody who gets ideas in the shower. It’s sitting in a car driving down very Midwestern streets.

I did that too back when it was safe to go out!

So, you have a chapter on procrastination in your book. I giggled at how you turned in a blank CD to your professor and just pretended there was something wrong with the file that was supposed to be your class assignment.

Obviously, you had to do something different to get this book out there. Can you tell me if your procrastination was still a problem when you were working on the book and how you overcame it?

The thing about procrastinating is regardless of whether you’re doing something boring or the thing that you’ve been telling everyone you want to do for a long time, it feels good to not do the thing you’re being told to do. I have a pretty good balance of never wanting to do the thing I’m being told to do while also desperately wanting the approval of anybody who’s remotely in charge of me. So that part of my brain took over a lot of the time where I’m like, “I need my agent to like me. I want the publisher to like me.” Usually what I would do is having the routine of a drive to a coffee shop and sitting there for however long and pretending to work and then actually going to work.

I had to play the game of, “If I write for 30 minutes, then I can look at Twitter once,” which is ridiculous that I’m almost 30 and my lizard brain is still like, “What’s the treat that I get for doing even the smallest amount of work?” I probably embellished how much of a procrastinator I still am. I’m fortunate enough to mostly like the job that I’m doing. Sometimes it feels like I’m procrastinating real life by writing about things that happened to me 20 years ago. So I definitely did procrastinate, but probably not. Then it was not turning any blank Word docs into my publisher. Like, “It was so weird! There were words on it and now they’re gone.” They’d be like, “You tried that last week.”

How did you find the balance between personal essays and satire when you were writing this book? I’m wondering if it’s difficult to switch in between things where you’re not the character in one piece but you are the character in another piece.

The thing I found easiest was going by thematic section. There’s five sections of the book. Part of that is because that’s how I wrote the pieces, grouping them together. It was helpful to see “What am I talking about? How much am I talking about each of these things? Is there an equal balance?” It was also helpful to see if I wanted an equal balance of personal essays and satirical pieces, mostly just in number, not necessarily in length.

A satirical piece can feel like a breath of fresh air after you read like a big, long thing. That’s why I tried to work through that balance. As far as switching gears between the two, because I’ve been writing those conceptual circle pieces for a while now, if I have like a solid idea I’m able to write a full first draft fairly quickly. It takes me a lot longer to write a personal essay. Usually what I do is I would have a day where I’m like, “I’m gonna finish the section on being professional.” And I like, “I have a couple of satirical pieces left and I have a personal essay left” and I would decide whether or not I was in the mood to talk about myself or think about something else entirely. It’s very much like a, “What am I feeling in this moment?” kind of thing. I’m not somebody that can crank out a satirical piece and then also write a really in-depth personal essay. The essays I had to be in a mindset ready to talk about whatever personal thing I was going to be talking about.

How did you make the leap from writing and editing greeting cards to full-length humor?

That came mostly from an itch inside of myself, feeling like I wanted to be writing something else. Like most people who graduated in the early 2010s, finding any job that was going to help pay off my student loans was my initial goal and Hallmark did that. And it also somehow applied to the degree that I got.

Hallmark was a very good introduction to adulthood as well as being a pseudo graduate school where I was learning things about the writing world that I wouldn’t have learned in school that I only had to learn on the job, learning that I enjoy editing and I can do it, but the thing that I actually want to do most of the time is write.

Making that switch from working at a corporation to doing quite literally the opposite of that came from the feeling of, “This is a thing I want to do and if I don’t do it now, I don’t know if I’m ever going to do it.” The reason I left hallmark was I was offered a job at an advertising agency. I left Hallmark with the assumption that I’d be writing more and I’d have more creative liberty and it wouldn’t be just writing the same things about birthdays every couple of weeks.

When I got to that ad agency, I was like, “Oh no, this is not the thing that I wanted.” I realized that even if I was writing more, I needed to be writing about something I cared about, that didn’t feel like it was soul sucking in order to do that job. I pushed myself into the pool of freelance writing because I was in a job where I was miserable.

I had months where I was freelancing for Hallmark actually. I had a good four or five months where I didn’t get any humor pieces accepted. Everything I wrote was rejected, but for good reasons. That switch from working at a company to working for myself was not as gradual as it is for some people, which mostly came being at that advertising job and realizing that I don’t have a full load of creative writing clients, but I would rather try and stay afloat in that pool than try and survive in this one.

How were you able to manage your time and overcome the hiccups of launching your career?

I definitely had panic moments where I was on Indeed, just searching creative writing jobs anywhere and was like, “Should I go back to work?” Fortunately, I was able to freelance for Hallmark because I had been away for whatever allotted amount of time that I needed to be away for. So that was enough of a small, steady thing that I was able to start figuring out what I want to write.

I started looking at the websites that I read to see if they were hiring writers and if they accept submissions. I saw that Bustle was hiring part-time writers so I applied for that. Freelancing for Hallmark and getting that part-time job with Bustle were the two things that set my anchor so I could start to figure out the fun stuff that I wanted to do. But I didn’t jump from writing content for a women’s website to writing a book overnight. Trying to build my portfolio of pieces that were actual things that I wanted to be writing took a while.

It was a lot of writing humor pieces. Then as I started to build up enough of those pieces, I was able to start getting this portfolio of the stuff that represents me and the stuff I want to write and was helpful to try and talk to a literary agent about turning that into a book.

So would you say you got rejected a lot? How did you cope with that rejection?

Probably a lot of crying and feeling like everything that I’ve written is bad. My brain still does that a little bit. As cliche as it sounds, I have grown a thicker skin from mere exposure. Hearing a “no” from a place where I submit a one-off piece does not feel nearly as bad as it felt when I was first trying to get things accepted.

Part of that is because I know that I have had pieces accepted by places that were dream publications. So I have that the part of my brain, that’s like, “No, you you’ve done the thing. You can do the thing. And you getting a no does not mean that you’re a bad writer. It doesn’t negate everything you’ve ever done.”

Every single day I was trying to write at least one good new thing that I could submit so that I would have a volume of things I could use and at least one of them was a good fit. Obviously not all of those pieces were good, but that first acceptance always feels so good. The first piece I got accepted when I started freelancing was for Bust and was “Bath and Body Works is the Suburban Nonsense I Crave,” which ended up being in the book. It’s one of my favorite things I’ve written.

It does feel a little better knowing that every other person I know who writes or does any kind of creative field has been rejected more times than they’ve been accepted and even people I admire still get told no. So yeah, knowing that it has less to do with me as a person and more just like, it’s a job. People are gonna say yes or no based on what’s right for their publication.

So what’s next for you now that you have your first book published?

I have ideas for book two. I’m in very early stages of pitching that. It will be another collection of funny essays and satirical pieces. I would love to write for TV. I’m in very early talks about how to adapt Weird But Normal into a [TV] series, what that would look like as some sort of fictionalized thing. And also just hoping that we all don’t have to live inside of our house for the rest of our lives.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I touched on this a tiny bit, but I’m trying to be conscious of the fact that I’m promoting something in a time where there are much bigger things going on. While big things are going on, I still am seeking out little bits of like levity that don’t ignore what’s happening, but at least lift a tiny bit of the weight off of your shoulders. There are a lot of writers and comedians who have dedicated their days to fighting for racial justice and doing things within their own community to like help with homelessness and help with issues that disproportionately affect Black and brown people.

I hope that is the thing that continues and it’s not going to stop. Part of thinking of ideas for this book was like, “I don’t want to write a book that feels like all I’m talking about is I’m a half-Asian, half-white woman who’s living here and I’m this age.”

There’s been this weird, both encouraging and disheartening sway in a lack of representation in any sort of inclusive voices, anybody who isn’t basically a rich white man. There’s been a huge sway from things we haven’t heard from literally anyone else to acknowledging that we need to hear diverse stories to everybody needs to hear about everybody else. And kind of using that as people of color can only talk about being a person of color. Women can only talk about being a woman, anybody who identifies as LGBTQ can only talk about that.

A thing I appreciate and the people that I read and follow, like Samantha Irby and people like Patti Harrison, we’re able to consistently do things that are so funny and also acknowledge the fact that their experience is shaped by who they are. But that is not the only thing there. I don’t know people who have been able to exist in these traditionally exclusive spaces in a way that doesn’t feel like they have to like capitalize on their differences. That’s a thing I’ve been trying to figure out how to do.

I love that people are excited to read books by women of color. I love that people are wanting to support Black-owned bookstores. I also hope that we get to a point where we realize that’s not the beginning and end of who a person is. The whole point of my book is like, “I hear all these things that shaped who I am and some of them are specific to me, but they’re all under this guise of no part of who you are as a person exists in a vacuum.”

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?