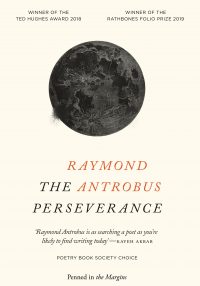

Congratulations on the sweep of prizes you’ve won for The Perseverance – most recently the 2019 Sunday Times/University of Warwick Young Writer of the Year Award. In your speech at that ceremony you made reference to building a new canon, and you’ve spoken elsewhere about the importance of a writing community. How do you find the London poetry ‘scene’ – a word which evokes both canon and community? Are they antithetical?

Thanks! In that speech I was talking about revising the literary canon we have as well as building new ones. We can customise our canons. It took me a long time to develop the confidence to do that. I studied O’Hara, Lorca, Larkin, Neruda, Walcott and I learned from their work but I became a better poet once I stopped trying to emulate them. I say that even as someone who has not done very much formal academic study of poetry or writing, but I have spent a lot of time teaching and visiting schools and universities where I often feel disappointed with how narrow the required reading lists are still. I feel lucky to have been nurtured by open mic and Slam communities – not just in the UK but Germany and the States. I had spaces where I could share my writing and be excited to hear others. That’s been invaluable to me and I’d say even in those spaces I became a better poet when I stopped trying to win Slams. I aligned my motivation with the poems I had to write rather than the poems that I assumed audiences wanted to hear. Developing critical community came a lot later and I had to be very deliberate about that. I owe some of my development to The Complete Works and to Cave Canem, both of these programmes put me in spaces where I didn’t have to be defensive about what I wanted to write and how I wanted to write it. They are both spaces designed for poets writing from the margins.

The collection and one of its poems is named after The Perseverance pub in Hackney, which I understand is still open today. I was struck by the strong sense of place in the collection. Perhaps you could expand a little on your choices about how you represented London, maybe even specifically Hackney, in these poems, and the mediation of public and private in your work?

I grew up in Hackney so this wasn’t a stylistic choice. It is where my voice comes from. Nowadays when I talk to people who didn’t grow up in Hackney it’s like we’re talking about two different places. The gentrification of the area really hurt and angered me at first (especially when I was teaching in the area and was losing students because their families had to be relocated because their council homes were sold off). I’ve had to let that go and accept the changes. I visited a high-security men’s prison recently and a few of the inmates grew up in Hackney too. They had read The Perseverance and told me how much they enjoyed seeing their area represented in my poems. Most of them have been in prison for over ten, fifteen years so they don’t have the full picture of how much Hackney has changed but I found the fact that these men identify with the poems very affirming. I’ve been a private poet for most my life. I was writing as young as six and I didn’t start sharing my work until I was around nineteen, becoming a poet publically moves you from small l literature to capital L literature because now it’s public so you begin or pick up conversations with your personal history and the history of your country and language. There’s an Albert Camus quote I love that says ‘I have never written anything that was not, either directly or indirectly, linked to the country in which I was born.’ This realization deepened my relationship with both reading and writing.

In one of the most-discussed parts of the book, you redact the entirety of Ted Hughes’s poem ‘Deaf School’ with thick black lines. Another poem, ‘The Mechanism of Speech’ is an erasure: certain words from Alexander Graham Bell’s lecture have been selected to form the text of the poem, and the rest erased. I wonder about the difference between these two forms of redaction: in the one, the absence is clearly visible in the black line, and your poem comes after, as a response; and in the other, you cherry-pick from Bell’s words to form your poem and the only record of absence is white space. How do you think these differ conceptually?

Initially I wanted the Ted Hughes poem to be struck through rather than redacted so it would still be readable but this wasn’t going to fly with the Ted Hughes estate. I’m on a small press and we couldn’t afford a lawsuit so we went with a full redaction of the poem. It was more cathartic to do it that way I found and it ends up saying more. I’ve had some great responses from D/deaf students I’ve shared that poem with. One twelve-year-old student pointed out that the redacted lines look like audio channels that he’s seen on his audiologist’s computer screen when they were programming his cochlea implants. This for me is an example of how creativity at its best inspires new ways of understanding each other. This is why creativity always needs a place in education. As for the Alexander Graham Bell’s erasure, the first draft of that was over ten pages. The initial idea was to have a pamphlet-length erasure, but that didn’t work so I tried to make it a sequence but the more I thought about that the more it irked me that I was giving Bell so much room, so I went with the one short section that ended up in the book. I have my own ideas about how these erasures compare conceptually but I don’t want to get in the way of someone else’s ideas, which might be more interesting than mine, like the boy who told me about the audio channels.

Several of the poems in the collection engage with historical texts and the history of the D/deaf community. Some of these names may be familiar to your readers (Helen Keller, Charles Dickens, Alexander Graham Bell) while others were unfamiliar, at least to me (Laura Bridgeman and Mable Gardiner Hubbards). You refer to people from the recent past as well, with poems about Daniel Harris, a deaf man killed in the USA in 2016, and three deaf Haitian women killed in 2016, Jesula Gelin, Vanessa Previl and Monique Vincent. In offering a kind of voice to those who are no longer with us, you put these people in conversation with the reader. What do you hope your reader takes away from that conversation in which you are a mouthpiece?

I can’t tell anyone what to take away from my work, that is what capital L literature is in some ways, a conversation with the ghosts all around us. Mable Gardiner Hubbards was the deaf wife of Graham Alexander Bell and I managed to read excerpts from her diary. It’s an upsetting read, she was so deeply ashamed of her deafness and much of that seemed to come from her husband’s psychological abuse. Daniel Harris, Jesula Gelin, Vanessa Previl and Monique Vincent – what happened to them was sad, despicable, a capital I Injustice that was totally preventable. If their deaths aren’t spoken about then we are all in danger because the ignorance that killed them lives on.

There is a long poem telling the story of an anonymous woman named Samantha, which is based on interviews, as well as another poem based on a conversation, ‘Conversation with the Art Teacher (a Translation Attempt)’. How different was it to tell the stories of people you had met compared to telling the stories of people you had read about? How different was it to tell the stories of people who are alive but not named, as opposed to named but not alive?

Well those conversations (Art Teacher and Samantha) are the stories of Deaf friends of mine. I feel honoured that they trusted me to share some of their story. I didn’t just want to just mournfully highlight the persecution of the Deaf but I wanted to uplift all of us and honour the ways in which we persevere. I feel connected to D/deaf communities around the world and have been welcomed into many spaces in the last few years. I’ve visited deaf schools in the US, Jamaica, Trinidad, Ukraine, Bali and around the UK. The global social stigma of people living with disabilities is so profound that I would call their experiences human rights violations. There’s a lot more to say about that.

You’ve spoken about how poetry is essentially a form of conversation. ‘Miami Airport’ however, is not so much a conversation as an interrogation. It’s also one of the few poems in the book which isn’t left-aligned. What’s your relationship to your poems as visual arrangements on the body of the page, as opposed to records of spoken or signed language?

At one point my ambition was to be a photojournalist. That shows up in the poet I’ve become. Two hearing poets that taught me a lot about shape and space are Mimi Khalvati, who was my tutor while I was on the Complete Works programme and Robin Coste Lewis, who was my mentor when I was at Cave Canem. Both of them had a way of speaking about poems before they’d even read a word in it, they’d have us look solely at the shape of a poem and ask, ‘Is this something you want to read.’ This renewed my questions about what poems are and can be. They taught me a lot about how to charge white space so it pulls readers in. I will also say that one of the reasons The Perseverance took so long for me to write was because I was grappling with the question of how to write a book in a language that has harmed and alienated so many of the people I want it to talk to and with. Illiteracy in Deaf communities is very high and the written and spoken word is privileged in ways that continues to cause harm. But I sought out D/deaf poets like Raymond Luczak, Ilya Kaminsky, Meg Day, Douglas Ridloff, Dorothy Miles, Bea Webster, Donna Williams, Richard Carter and all of these poets showed me what sign language does in the air and in some cases on the page.

I understand your next book will be a picture book for children, Can Bears Ski? illustrated by Polly Dunbar, who is also deaf. Was it different to consciously write for a young audience? What do you think adults can learn from the language(s) of children?

I’m so proud of Can Bears Ski? It’s being published by Walker Books and I can’t wait for it to be in the world. Initially it was written as a poem but it never made it into The Perseverance. Then while I was visiting deaf schools I would always look at the libraries and I remember feeling let down by the lack of representation for D/deaf children in any of the books. Then I had a vision to rewrite what I considered a failed poem as a children’s story, something that could be useful and fun for D/deaf children, particularly if they have hearing parents (as most D/deaf children do). It’s not so much about learning from the language of children, it’s a lot more specific than that. It’s learning how to communicate with deaf people generally (especially if they rely on lip-reading rather than sign). I couldn’t sign until I was 11 and my parents never learned it so Can Bears Ski? focuses on communicating with deaf children who can’t yet sign. Polly Dunbar was the perfect collaborator for this project; her illustrations precisely capture much of what I remember about deafness as a child. We didn’t meet in person until we’d finished the book and it was very emotional the first time I read it aloud with Polly in the room.

Photograph © Suki Dhanda

The post Raymond Antrobus | Interview appeared first on Granta Magazine.

Be First to Comment