Writer Sarah Hagi is said to have originated the highly relatable, often quoted, and even merchandised tweet, “Lord, grant me the confidence of a mediocre white man.” It is a phrase that many women have muttered to themselves in the midst of a bout of imposter syndrome, when some sense of self-doubt creeps in and we wonder, how do white men have the audacity? Where do they get the sheer nerve?

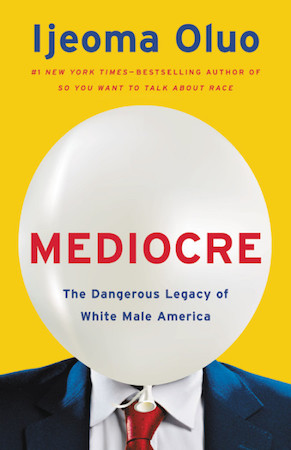

Ijeoma Oluo in her new book, Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America, takes a deep dive into the motivations, expectations, and the root cause of why so many white men move through our society with extreme confidence and righteous entitlement. Mediocre reveals not only how dangerous it is for women and people of color to be on the receiving end of such entitlement, but how failing to meet the ingrained and deep-seated expectations sowed into the white male psyche for generations has proven to be a tragedy for white men also. Fresh off of the success of So You Want to Talk About Race, through a historical, political, and sometimes personal journey, Oluo attempts to answer one of the most mysterious questions of our time: Why in the hell are white men so mad?

I spoke with Oluo about exactly that question, the ways in which America can move away from the white male supremacy design, and if it is human nature to align yourself politically with others like yourself.

Tyrese L Coleman: A central theme is that America is stuck in a system that is designed to uplift and reinforce white male supremacy, and that in doing so, everyone suffers, including white men. I’m curious as to whether or not you think our reliance on this design can or will ever be undone. And if so, will it be in your lifetime?

Ijeoma Oluo: Absolutely. I think it can be done. I think that right now, we are seeing with the changing racial demographics in this country is this mad, really intense effort to entrench these systems, even in non-white spaces. And so that’s something that we’re going to have to work extra hard to resist.

But, what I’m more likely to see in my lifetime is not that the system’s gone, but seeing pockets where we’ve disengaged from it and are working and building. I think it’s gonna be piecemeal and local. The system didn’t just land on us all of a sudden, it was built up, and it’s gonna have to be torn down piece by piece. What I’m hoping people see in this book are the reflections and the choices they’re making in their cities and towns. We can start making better choices in our workplaces, our towns, our churches to start dismantling these systems all over the country. That’s how the system was built. That’s how it could be taken down.

TLC: Do you think we are moving towards a place where this is actively happening as we sit here right now?

IO: I think that in some places it is. Well, first, I wanna be very clear, there have always been activists, right? And even people within the system fighting to try to do this work for a very, very long time. So, yeah, I do think that we see bits and pieces of it. The “defund the police” effort is a huge part of it, the fight to de-weaponize one of the more violent tools of democracy in this country. We’re seeing it in some school reforms around the country. We’re seeing it even in the election and leadership of people like The Squad in congress, you know? And so I think that it’s absolutely being done. People have been dedicated to this effort for the entirety of human history.

But if there’s one thing that the book shows is that as hard as some of us may be working, there are other forces working just as hard to try to take back any gains we make. So, it really is going to take a larger level of awareness and a lot more dedication in order for us to make changes last.

TLC: History has shown us that, in times where this country takes steps towards the social and political progress that you mentioned, moving outside of this white male supremacy design, we then take five steps back. For example, we saw this after the Civil War during reconstruction. We saw it in the 70s and 80s after the Civil Rights Movement. We saw it with Trump after Obama. What is your take on why this happens? Why do we revert back to the status quo? Is it—and I hate to say this, but for lack of a better word—a comfort level?

White male identity is—right now and has always been, as far as the history of this country—a reactionary identity, not a proactive identity.

IO: I think there’s a couple of things. One, for people, for many people of color, I wouldn’t necessarily call it a comfort level. But I would say there is a deep fear of the unknown. We have history to show us that pushing too far means the backlash would be even harder or that there’s really a limit to what can be accomplished. And I think that we saw a lot of this in this election where people knew we absolutely needed to get Trump out of office but also, I think that many people of color had this pragmatic idea that white people were only gonna vote for so much. But also, I think it’s really important to recognize that Black America has bought into a lot of these white male ideals.

But I would also say it’s really important to recognize, and it’s something that I hope that the book can make clear, that white male identity is—right now, and has always been, as far as the history of this country—a reactionary identity, not a proactive identity. And that means that, where it feels like it’s being shifted or pushed or threatened, it’s stronger than it ever is. And what we see is a direct backlash when something is shifting. If your identity is only based, comparatively, on what someone else is doing or what or how much further ahead of others you are, that means that every bit of progress is a threat.

TLC: You use a quote from Woodrow Wilson, “the white men of the South were aroused by the mere instinct of self-preservation.” And that goes to what you were just saying, the self-preservation instinct. Is that driving the reactionary response?

IO: Yeah, absolutely. I think it’s driving not only the reactionary response on the right, but also the reactionary response on the left, where we immediately start hearing that things have gone too far. The immediate fear. Even now, when we talk about why there wasn’t a bigger landslide [during the recent Presidential election] and people are saying, “Oh, well, you know, you said defund the police too much.” “Things don’t center us anymore, so that must be why things are the way they are.” And so it’s not only a response on the right, it’s a response across the board that is incredibly reactionary. And that also doesn’t get investigated, because the moment white male identity isn’t under threat, it goes dormant. No one stops and goes, “Why, why did a Black man get elected and I freak out? Why did that happen?” No one does that.

So, I think that’s the real danger. But also the fact that we then treat that response as an excuse to not push further. If we don’t push further, we don’t get the backlash. Then what? Well, then we’re stuck where we are forever, right? But people pretend like it’s not a natural response that’s going to keep happening every time we make progress. People like to pretend there’s a way to make progress that won’t threaten white male identity. And there simply isn’t. So, in order to move forward with a society that isn’t stuck in this design, we have to actually confront the white male mediocrity that is in power.

TLC: That reminds me of your chapter sections on Biden and Bernie. The theme I got from those sections was that, “white man is gonna white man.” They’re going to align themselves with those that are like themselves. There’s always this argument that we should move away from identity politics but that, in and of itself, is an example of identity politics, especially when you are aligning yourself with the policies and the legislation that help your particular identity. But is that a part of human nature? Isn’t it natural for them to do that?

IO: I would say no. I would say what is natural is to see affinity. And when we pick who represents us, often affinity is what we choose. Whether this person represents our interests and represents who we are.

But there are two things I think that have been deliberately constructed. One is how white men view community and their best interests. And it’s very exclusive. Who we view as community, who I view is community, and whose futures I tie to my own is important. But also are your definition of well-being, your definition of best interest and what those interests are deliberately constructed to be harmful? That can make a huge difference.

I can look at someone like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who is not Black, and see affinity with her because I can see the way she is fighting for poor communities. And that’s how I consider my community because my community is about bringing people together and solidarity. It is not about being on top and being more powerful. That’s where the danger is. And politically, that’s what we have with white manhood as a political construct, an identity based on power and oppression. And that means that you can never actually find an identity that reaches beyond that. You can never actually find cooperation or shared interest if it would threaten your power.

And that’s really the difference. It is completely natural to find affinity with people to say “this is us, and you are you.” But if what defines it means that, even when it’s in your best interest, you can’t expand, you can’t bring other people in, you can’t find shared interest because your interest is always about doing better or having more than, then we have a serious problem, especially in a democracy.

TLC: In thinking about the process of transferring power or equalizing power, you write, “…yes it will offer some real benefits for you, but it will not always benefit you. Sometimes it may seem like justice is disadvantaging you when the privileges you enjoy are threatened.” Do you think that in order to create equality, there has to be a giving up of something in order to benefit others? Or is there another way of looking at it that could make it feel less like giving up? Do white men, in order to come to a reckoning with history, have to do the work of giving up some level of power in order to equalize things?

IO: I think, no matter what, the power has to be given up. When everyone is doing better, you do better, no matter what. We all do better.

But there isn’t a one for one replacement for an identity built on being better than everyone else. And so that means that it will at times feel like a loss that has nothing to go in its place. And the only way you can value what replaces it, is if you let it go. You can’t hold on. You can’t say, “I’m gonna hold on to this power while I get used to not having power.” It doesn’t work that way. And so that’s the part that’s important. And it’s also important that we recognize this because we can’t keep saying we’re gonna wait until white men are comfortable and ready because that in and of itself is upholding white male supremacy. Their comfort is so important that we’ll continue these systems that are literally killing people because white men aren’t ready yet. We haven’t found a way to convince them yet. That in itself is saying a lot about, respectively, how we value white men compared to everyone else.

TLC: For a long time, the default has been “white” and “male.” For example, when you think about the terms “fiction” and “women’s fiction” to differentiate genres. The fact that one has to differentiate “women’s fiction” means that “fiction” is not for women. But I feel like we’re heading into a world where white men are being specifically identified as “white men,” highlighting them as individuals, whereas before, it felt like they were a conglomerate.

You write about how angry white men are, and I’m wondering if part of the desperate anger that we see and that you experienced in your personal life as a result of white men is related to a spotlight on them as individuals, so that they’re now being required to show their worth rather than relying on being a part of the default?

IO: I think of it somewhat in the opposite, which is that there was never any light on the system. The system was fully operating for white men and yet we had this idea that each white man was an individual and never responsible for what he did collectively. We weren’t saying, “We have a white man problem.” It was, “No, no, no, no, no. We have a problem with this one man. And this one man.” Collectively as Black people, we were always saying, “Look, white people are gonna do this shit, right? This is fucked up.” How many times have you been asked if people are racist and you say, “No, you have one racist person. People aren’t racist.” Or asked to seperate? “We’re not all bad.” Even when we talk about the police. “No, we have one bad cop. We don’t have a systemic problem.”

The problem with that is that it absolves white men from accountability. It also stops them from seeing how the system is screwing them over because it’s invisible. The system that they are a part of that is supposed to magically make them all happy, successful and powerful is invisible to that. All they know is that they’re failing.

I do think we are seeing increased accountability in the last few years. Talking about #MeToo, talking about race. We’re seeing white men who’ve been doing what they’ve always been programmed to do, feeling like they’re being cheated. But not only are they not getting rich and famous, not only do they not feel successful, but now they’re being punished for doing what they’ve been programmed to do. And I think that, for them, it feels incredibly unfair. It feels like they’re being targeted and maligned because, as a society, we have allowed white men to not be responsible for how they participate in systemic oppression. And now that they’re being held responsible, they’re basically like, “Oh, since when?” This is a tragedy. They’re allowed to center themselves because we haven’t moved far enough away from the narrative. It’s still all about these white men. They don’t get that it’s not all about them.

I think that’s part of what we’re seeing, this mix. White male power got to be ubiquitous for so long. It got to be the air we breathe. And now there’s suddenly some accountability. And I think white men, too, have always been angry and bitter by the failures that have been placed upon them. They aren’t as successful. They’re not as successful and powerful as they were told they should be and because we never talked about the system, they weren’t told why. And so they were told to blame us, blame women, blame people of color. And now, on top of that, they’re like, “I’m already miserable and you want to yell at me for grabbing someone’s ass at the workplace? Since when?” We’re seeing this anger and desperation because they aren’t conditioned to accept responsibility. They have refused to learn how they participated in systems of violence.

TLC: I mean, it’s funny how the stereotype is of an angry Black woman, right? But what I’ve read in Mediocre is the angry white man archetype. I can’t help but think, “What the hell do they have to be so angry about?” They’re still ahead of everyone else when you look at employment, pay, housing, education, everything. That’s what you were just addressing, this unrealistic level of expectation and then being slammed down by reality. Even yet, still, most of the world is like, “okay, and…”

IO: I can understand so much about whiteness, but I can’t understand what it would feel like to be 40 and realize that you’re part of an unfair system. You know what I mean?

We need to recognize that we have been programmed to view harmful white male ideals as leadership and step away from it.

The difference is that white men have been so coddled that they don’t know they can survive this knowledge. They can grow past it. We have. We are living examples of going past the knowledge that this system sucks. We still do what we can. We still care for our families. We still try to find happiness.

But there’s this idea that a white man shouldn’t have to, and they have no practice in it. And I’m sure that’s a huge existential crisis to realize you’ve striven your whole life for something you were never ever, ever gonna get. You know, when I was a kid, no one said to me, “You could be president one day.” But we were told to strive and try our hardest, because we had to take care of our family. Because we had to be something. But not “it’s coming to you.”

White men were told they could be president someday. No matter what. Even if your kids hate politics, don’t pay attention to anything, is a total asshole. There’s still someone telling them that they could be president someday, and they will become president someday.

And there’s almost a cruelty to it—the lie that’s told to white men—because only so many of them can be president. Only so many of them can have their own company. Only so many of them are gonna be rich. There’s limited resources in the system that siphons up the majority of profits for business owners and investors. So it is a childish, oversensitive place that white male America often finds itself in. And I don’t know what it’s like, and I can’t imagine what those growing pains are because it’s just a luxury that so many of us never had.

TLC: What can those of us who aren’t white men do to help move our society forward so that everyone benefits? Specifically, how can we disrupt the design?

IO: One is we have to be really aware of where we uphold it. This is where we do the self-audit and say, even for me as a Black woman, where do I, and in Black culture, define success as a dude, putting on a suit and talking a particular way instead of accomplishments that may be divorced from white supremacy and patriarchy? Where am I spending my money? What am I consuming? What am I supporting? What conversations am I having around that to free myself and my family and my community?

But then also it’s really important for us to look at systems that were born in these ideals and then continue to uphold the status quo and fight for change. Starting in your school district and going through your kids textbooks and see what’s in it. Look at school funding. Look at teacher recruitment. Look at what we can do at a local level because, obviously, that’s where the impact of everyday life is but it’s also the breeding ground, the training ground for our national politics.

These national politicians don’t just appear out of nowhere. They come up through the systems and are told what to expect. I think it’s important that we look at our systems and say, “Okay, you know what? Maybe I can’t influence what’s happening in D.C., but I can influence what’s happening in my city council. I can take a look at what’s being promoted there. I can look at what businesses I’m supporting locally. I can look at what I’m saying to my kids about terrorism and manhood and how it’s being defined. I can have those conversations.” I think that that’s really where we have to start doing the work.

And then, of course, where we do have power on a national level, where we can vote and support and make our voices heard, we have to. We have to really check ourselves and recognize that we have been programmed to view harmful white male ideals as leadership, and we have to learn to recognize it and step away from it.

The post Ijeoma Oluo on Dismantling White Male Privilege appeared first on Electric Literature.

Be First to Comment