https://econsultancy.com/the-six-fundamental-elements-of-an-effective-content-strategy/

A strategy is an overarching diagnosis, guiding policy and direction, while a plan is the steps in the process that allow a business to progress with confidence. At its heart, every strategic process answers the same four questions:

- Where am I now?

- Where do I want to get to?

- How do I get there?

- How do I know when I’ve got there?

A good content strategy therefore needs to begin with a good understanding of context drawn from the competitive and brand situation as well as customer insight, which can then inform an objective, strategic direction and plan that can be executed through a coherent but responsive set of plans, actions and measures.

This enables businesses to set out a comprehensive strategic process for content that ensures the maximum opportunity for success.

The fundamental elements that may form a part of content strategy can be summarised in the following taxonomy:

1. Research/insight

This includes understanding user need, customer segmentation, the development of personas, review and understanding of existing assets and position via content inventory and audit, competitor and gap analysis and formulation of measurement frameworks.

2. Content management/resourcing

Incorporating content management structures necessary to establishing and maintaining appropriate structures, organisation and resourcing – information architecture (site structures, taxonomies, metadata frameworks); content management tools and practices; backup, versioning, archiving practices; analytics configuration; governance and standards; budgeting; resource requirements.

3. Content planning and objective setting

Including guidelines, plans, objectives and KPIs – brand positioning, purpose, point of view, guidelines, tone of voice; aligning content objectives with marketing/organisational objectives; targets, KPIs, success metrics, mapping outcomes to business value; concept development; themes, messages, topics; content calendars, channels, content type, format, integration; workflow (e.g. RACI); role of third-party/user-generated content.

4. Content production

The creation and production of content, including authoring, editing, asset production; content optimisation, accessibility, SEO; tagging and classifying; insourcing/outsourcing in production; the role of third-party tools and technology; content reuse.

5. Delivery/distribution

The execution and delivery of content incorporating the role of agencies and third parties such as syndication and aggregation, content distribution and channels.

6. Content review/optimisation

The evaluation of content, adaptation and optimisation – analytics evaluation, optimisation, revisioning, test-and-learn, user experience.

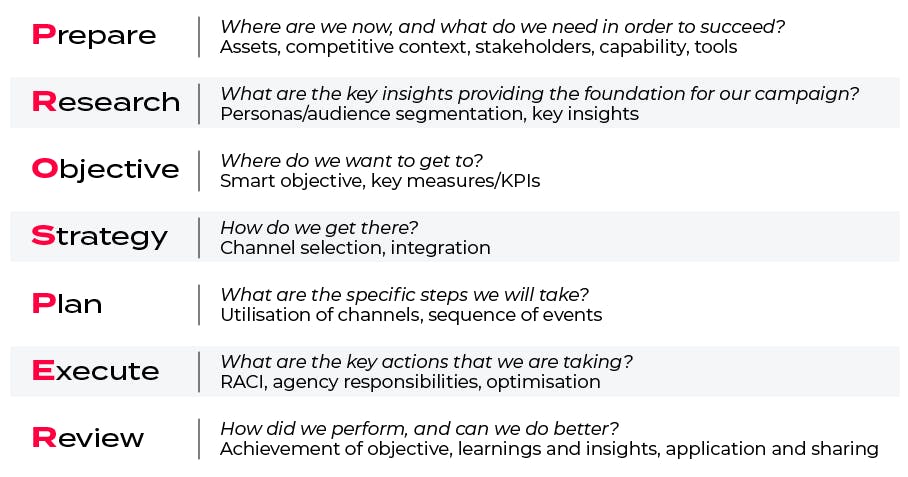

The PROSPER framework

These fundamental elements combined with a good strategic process support the definition of a good campaign process for content strategy, built around the acronym PROSPER:

Figure 1: The PROSPER framework

Source: Econsultancy

This model follows the outline for effective strategy and planning:

- Prepare and Research stages: Where are we now?

- Objective: Where do we want to get to?

- Strategy, Plan, Execute: How do get there?

- Review: How do we know when we’ve got there?

Taking each key stage of this seven-step model in turn, more detail around this process can be defined as follows:

Prepare

This initial stage is concerned with establishing and understanding the available resources, assets and capability, as well as appreciating positioning, context and environment. It is essential when setting out a strategy to develop an appreciation of the resources and capabilities that may be at the disposal of the team, so that the full range of possibilities are understood. This way, the team can avoid duplication of effort and maximise resources, also understanding what needs to be outsourced or supported by partnership.

The key question the team need to answer at this stage is: Where are they now, and what do they need in order to succeed?

Key activities include:

- Content audits to establish an understanding of available assets that might be used or repurposed, or areas of opportunity/gaps that need to be filled.

- Capability audit to establish what competencies, tools and technologies are available and what might need to be outsourced or supported through external partnership.

- Competitive analysis to understand competitive positioning and context and help define and map territory and opportunity.

- Situational analysis to develop understanding about the current environment and situation that might inform a strategic response. This might include the key stakeholders in the business (stakeholder mapping).

- Development of brand positioning/personality/tone to establish a voice. Good content strategy is rooted in a clearly defined brand positioning that brings clarity to tone of voice, territory, point of view, content themes.

Research

This second part in the “where are we now?” stage is focused on defining and developing understanding of customer needs, wants, fears in order to define the opportunity for strategic response.

The key question that needs to be answered at this stage is: What are the key insights providing the foundation for the campaign?

Key activities include:

- Research commissioning, aggregation and analysis: pulling together the relevant research material and outputs (quantitative and qualitative) for analysis to draw out key insights that can inform strategy.

- Talking to customers/users: there is no substitute for getting in front of real users or customers whenever possible in order to inform activity and response. The earlier in the process this is done the better.

- Audience segmentation: this covers the process of dividing people into subgroups based upon defined criteria such as demographics, psychographics, customer lifecycle, product usage and behaviour, media use. Econsultancy’s Segmentations and Personas Best Practice Guide contains useful frameworks and practices in this area.

- Persona generation: the development of user or customer personas as a representation of key customer segments, and the use and application of customer journey mapping. Econsultancy’s Customer Journey Mapping Best Practice Guide contains practical and useful guidance in this area.

Objective

Next the business needs to set a clear objective and goal in order to define what success looks like and set a target that can inform direction.

The question that needs to be answered is: Where do we want to get to?

Key activities include:

- SMART objective setting: this involves establishing objectives that are Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic and Time bound.

- Aligning goals and objectives: the brand’s over-arching goal should set a target that defines what success looks like. This should be measurable and time bound. The team may then set a number of objectives that ladder up to the over-arching goal.

- Identifying measure of success: what are the KPIs that will show when the campaign or activity has achieved its objective/s?

Strategy

This stage is concerned with identifying the key ways in which the team will achieve the objective that they have set. A good strategy should detail high-level actions, considerations and preferences.

The question that should be answered at this stage is: How do we get there?

Key activities include:

- Strategy definition: this includes identifying how the start point relates to the end point, how activity can be integrated right from the very beginning, identification of the key channels to deliver the objective, the balance between consistency and channel specialisation, principles for governance of activity and opportunities for test and learn.

- Strategy communication: give clear, concise expression and communication of the objective and strategy in order to ensure alignment from the start.

- Strategy development: taking account of changing contexts, circumstances and environment, strategy needs to be consistent enough to define a clear direction but fluid and responsive enough to reflect shifts over time.

Plan

The plan sets out the specific actions, activities and steps that the team are going to take in more detail, and defines how they are going to utilise specific channels.

The question that needs to be answered here is: What are the specific steps that we will take?

Key activities include:

- Plan definition: laying out the order of activities and key actions to be taken, including detail of how the team are to use individual channels (e.g. keyword strategy for search, content deployment, targeting methodology, media schedules), identification of tests that they are going to conduct, tracking and testing methodologies.

- Plan communication: give clear, concise expression and communication of plan and activities and how this relates to the objective and strategy.

- Plan development: plans change faster than strategies, so plans need to be responsive to changing contexts, circumstances and environments.

Execute

When executing, the team need to ensure good governance so that the plan and strategy are executed well, but they also need to have a clear understanding of the opportunity for in-campaign optimisation.

The question it is important to answer at this stage is: What are the key actions and who will take them?

Key activities include:

- Assigning responsibilities: this involves identifying in advance who is responsible and accountable, and who needs to be consulted and informed (using a simple framework like RACI[7]). It includes identifying key responsibilities across agency partners and internal team members for channel and activity management and execution.

- Tracking, testing and optimisation: the team should not wait until the end of the campaign to capitalise on the opportunity to optimise against their key objectives and goals. Tracking, testing and optimisation should be built into execution as a continuous process.

Review

At the end of campaigns, or at regular intervals, the team need to take a step back and identify what learnings they can take from the activity and how that can contribute towards continuous improvement.

The question that needs to be answered at this stage is: How did we perform, and how can we improve?

Key activities include:

- Measurement: identifying performance against the set goal and objective/s.

- Learning and optimisation: deriving insight and learning from the measures of performance, including identifying opportunities for improvement, efficiency, future testing hypotheses.

This article is an excerpt from Econsultancy’s Content Strategy Best Practice Guide.

The post The six fundamental elements of an effective content strategy appeared first on Econsultancy.