Pick up any newspaper or magazine, and you’ll see something that’s fairly unusual in the blogging world: most articles contain several quotes – words from people other than the author.

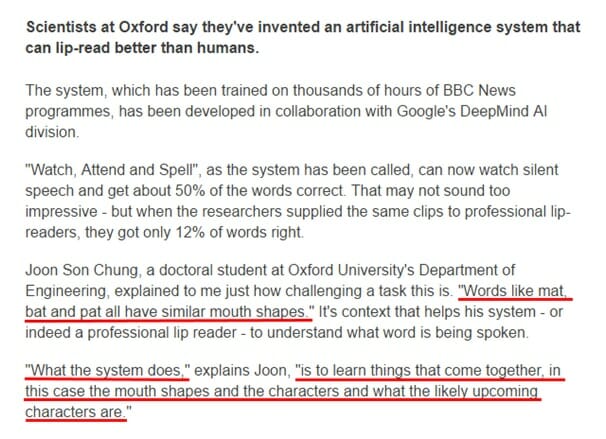

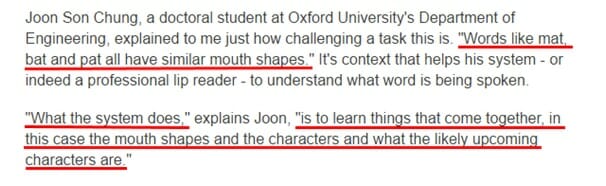

Here’s the start of a BBC News article, for instance, with the quotes marked up:

By including quotes in your blog posts, you can:

- Add authority to your own words. Perhaps you’ve got some great thoughts about parenting toddlers…but you’ll have more impact on the reader if you also include some quotes from other parents, or from experts in child development, to back you up.

- Break up your post. Quotes can be set apart from the rest of your text, creating extra white space and making your post look more interesting and engaging. If you want readers to stick around, you need to make your post easy to read.

- Add different voices. You might have a peppy, upbeat style – but you might want to quote someone who’s more forthright or who’s prone to going off on a rant. This can help you bring in a perspective that might not fit easily within your own voice or brand.

Selecting quotes to use in your post

You can quote almost anyone in your blog posts. You might go for:

- Fellow bloggers. This makes it easy to include and attribute quotes – you can just link to the original blog post – and also helps you build strong relationships.

- Subject matter experts. Perhaps you write about personal finances and you want to quote someone who’s worked in debt counseling, for instance. Try HARO (Help a Reporter Out) to find great sources, or simply ask around on Facebook or Twitter.

- Famous people. There are thousands of great quotes out there from well-known figure (historical and contemporary). If you choose to go down this route, (a) try to select quotes that aren’t too well-worn and (b) make sure you attribute the quote correctly. If you’re not 100% sure about whether a quote is accurate and/or attributed to the right person, check Quote Investigator.

In general, try to keep quotes relatively short: readers may not read a long quote, and if you end up quoting most or all of someone’s blog post, they may well object (as at that point, you’re essentially stealing their content).

How to put quotes into your blog posts

There are two key ways to use quotes in your blog posts:

- Use blockquote formatting (for quotes of two or more sentences).

- Use inline formatting (usually for quotes of one sentence, or less than a sentence).

If you’ve written essays in school or university, you’re probably used to both of these.

How to do blockquotes

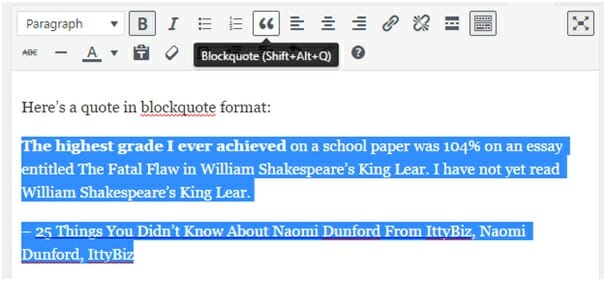

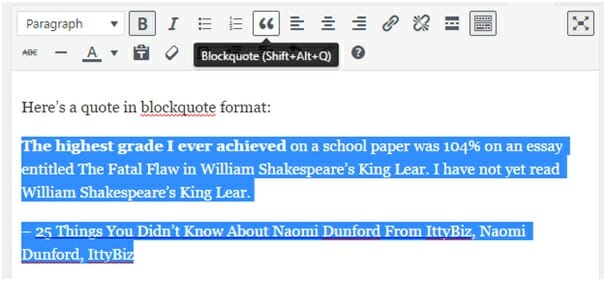

Here’s a quote in blockquote format:

The highest grade I ever achieved on a school paper was 104% on an essay entitled The Fatal Flaw in William Shakespeare’s King Lear. I have not yet read William Shakespeare’s King Lear.

– 25 Things You Didn’t Know About Naomi Dunford From IttyBiz, Naomi Dunford, IttyBiz

(It’s up to you where to place the attribution. I like to put them immediately after the quote, within the blockquote itself; some people prefer to lead with the attribution, then begin the blockquote.)

To create a blockquote in WordPress, simply highlight the text of the quote and click the blockquote button (which looks like quotation marks):

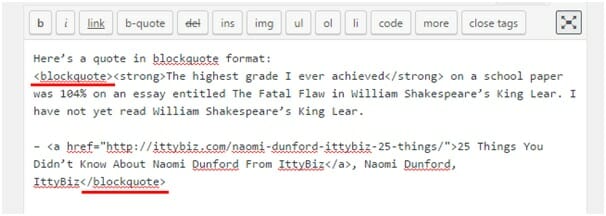

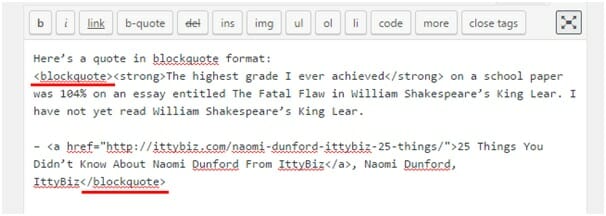

If you prefer to work with the “text” (HTML) interface in WordPress, type the opening tag <blockquote> just before your quote begins and </blockquote> just after it ends, like this:

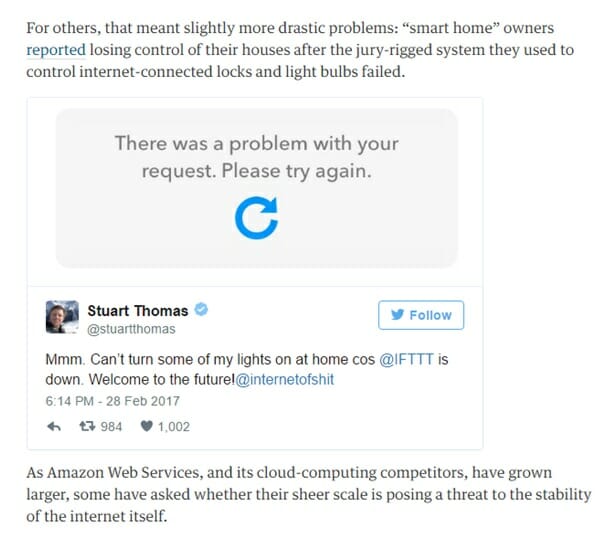

Another option, if you’re quoting a tweet, is to embed the whole tweet in your post. (This can potentially cause difficulties if it later gets deleted, though.) For instance, The Guardian’s article How did an Amazon glitch leave people literally in the dark? includes a tweet from Stuart Thomas part-way through:

How to use inline formatting

Using a quote “inline” simply means making it part of your normal paragraph, as we saw with the BBC News example:

This is normally done for very short quotes: one sentence or less. It’s possible to break up the quote to make it more like dialogue (as the BBC does in the second paragraph here).

You don’t need to do anything unusual for inline formatting: simply put the quote in quotation marks and make sure it’s clearly attributed.

Can you alter a quote?

If a quote doesn’t quite work when taken out of context, it’s OK to change or add a word or two: just make it clear what you’ve done.

For instance, here’s a long quote that might need cutting down, from Kate Parrish’s post How a Writing Residency Helped This Woman Return to Her Craft:

The literary world was foreign to me at that time, abandoned as soon as I’d graduated college. I was working in healthcare marketing, promoting outpatient surgical solutions for incontinence. Based in Nashville, I traveled the country meeting with urologists, OBGYNs and colorectal surgeons touting the benefits of an implant (“the size of a Peppermint Patty!”) proven to eliminate certain kinds of incontinence. I was 28 and at a professional crossroads.

Here’s the cut down version, which might work well in an article incorporating several quotes about 20 – 30 something women returning to writing:

The literary world was foreign to me at that time, abandoned as soon as I’d graduated college. […] I was 28 and at a professional crossroads.

When you alter a quotation, use […] to show where you’ve made cuts. If you need to change a word to help the quote make sense (e.g. to use a name instead of “he”), then put the change word inside [square brackets].

Incorporating quotes into your posts makes them more engaging and more authoritative – and can even help you with inspiration and structure.

If you’re not already using quotes, think about how you might bring them into your next post…and share your ideas, or your tips, with us in the comments.

This is an updated version of a story that was previously published. We update our posts as often as possible to ensure they’re useful for our readers.

Photo via GuadiLab / Shutterstock

The post How to Best Use Quotes in Your Blog Posts, Including Block Quotes appeared first on The Write Life.