http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/OnlineMarketingSEOBlog/~3/_eAaUjbgUiQ/

The post Break Free B2B Marketing: Lisa Sharapata of 6sense on the End of the MQL appeared first on Online Marketing Blog – TopRank®.

Brad Johnson is an author and blogger who helps writers discover their niche, build successful habits, and quit their 9-5. His books include Ignite Your Beacon, Writing Clout and Tomes Of A Healing Heart. For strategic content and practical tips on how to become a full-time writer, visit: BradleyJohnsonProductions.com.

https://feeds.feedblitz.com/~/623168752/0/convinceandconvertconsulting/

To increase conversion rates on your website, you need to understand its current state.

What is your overall conversion rate? Which pages are performing well (according to the numbers)?

Which pages are performing poorly? What tests can be carried out based on these analyses? What can you learn about your audience and your website from all this data?

Numbers tell many stories about your website. But without the right analysis, it’s difficult to get the vital pieces of information. What numbers are important? What should you look for?

In this short guide, I’ll show you how to improve your conversion rates by paying attention to the right metrics from your web analytics. Here are the 7 points you need to keep in mind:

From your website demographic data, you’ll get insights into who your visitors are, what might interest them, and their behavior on your website. With a tool such as Google Analytics, you’ll get a wealth of data about your visitors.

For instance, common demographic data include:

If you run a business where your ideal buyers live in a specific location, then you’d want to know how those visitors behave on your website. Are they converting? What’s their conversion rates compared to visitors from other locations?

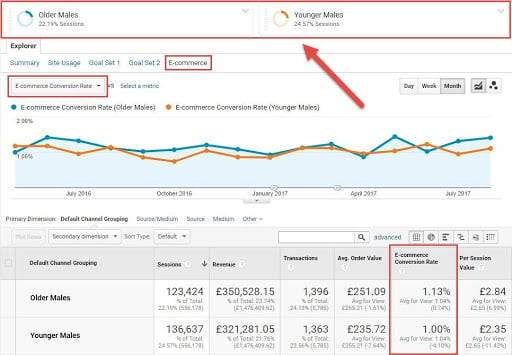

You can create segments on Google Analytics to make these comparisons. Another example is the age groups. Do older visitors convert better than younger visitors? What of 18 – 24 versus 25 – 34-year-olds?

You can even go further and include gender. For a page selling a gift item for men, what’s the conversion rates of female versus male for that page? This would help tweak your message on these pages.

Analyze conversion rates in Google Analytics based on gender.

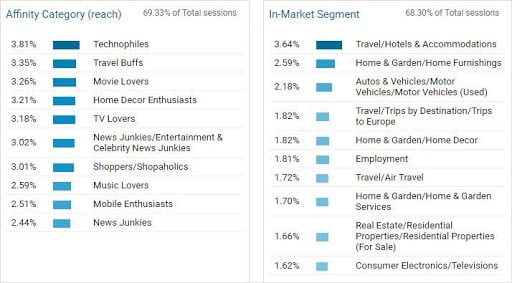

Furthermore, you can find the interests of your visitors. Depending on how deep you can dive, there’s a lot of information you can uncover from your analysis. This will provide information about the conversion rates of different demographic groups and where you need to improve.

Use Google Analytics to see discover the interests of your visitors. Use this information to see whether different demographic groups are converting.

When you go through numbers about your website performance, one of the main objectives is to understand your visitors. What does their behavior say about them? What does their demographic data mean?

Some important pieces of data to track to understand your visitors include:

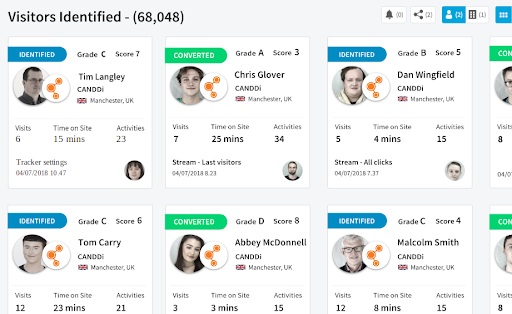

These details and more will help you understand your page visitors. More so, you’ll be able to predict their needs better and make attractive offers. One tool that allows you to understand your visitors is CANDDi.

Interestingly, this tool actually identifies your visitors. Thus, you can find more unique details such as their name, employer, time on site, and their activities.

CANDDi is a tool that identifies your website visitors. You can see unique details such as their name, employer, time on site, and their activities.

As a result, it’s easy to identify your leads and understand their needs based on their data. Furthermore, you can use these pieces of information to build buyer personas for your business.

In a nutshell, understanding your audience will help refine your messages for your ideal audience and increase conversions.

If you’re looking to increase conversion rates, you have to pay special attention to your landing pages because they account for most of your conversions.

According to WordStream, landing pages across various industries have a median conversion rate of 2.35%. Normally, this value will vary across different industries.

Landing pages across various industries have a median conversion rate of 2.35%. This value varies across different industries.

No matter your page conversion rate, you need to increase it. But first, you have to analyze the data. With a tool like Instapage, you can analyze details about your landing page performance. These include:

Apart from having an overall website conversion rate, you need to analyze individual landing pages for your marketing campaigns. By doing this, you’ll understand how effective each campaign has been in terms of conversions. More so, you get insights to make changes to your paid ads and their landing pages.

With a tool like Instapage, you can your landing page performance.

Beyond those numbers, you can also analyze user behavior on your landing pages. Do they read all your page content? Where do they click?

For instance, a tool like Crazy Egg allows you to see how users scroll through your page with the scroll map. Also, you have the heatmaps which display where visitors click on your page.

Crazy Egg shows you how users scroll through your page with the scroll map. Heatmaps display where visitors click on your page.

Another useful feature is the recordings, which show how users navigate your landing pages. With these pieces of data, you’ll get useful insights to improve conversions.

Over the years, page speed has become a vital part of web experiences. Due to the development in technology, visitors want your pages to load immediately. Otherwise, they’ll bounce off your page.

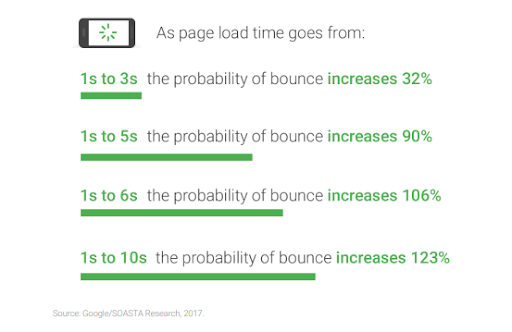

According to a Google study, the probability of a bounce increases by 32% once your page loads for 3 seconds. To further illustrate, another study found that Amazon could lose $1.6 billion in annual sales if its page loads 1 second slower.

A study by Google found that bounce rates increase the longer a page takes to load.

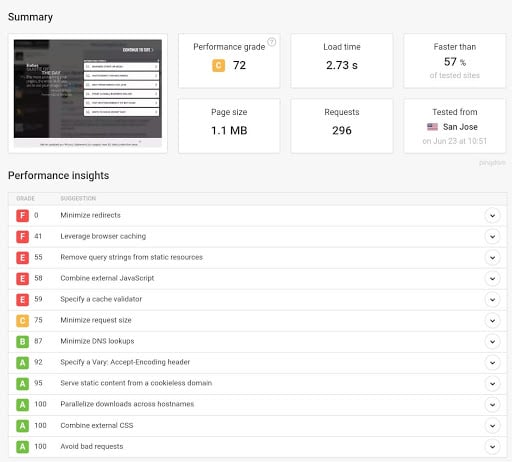

Fortunately, a tool such as Pingdom allows you to test your page speed. Depending on your ideal audience’s location, you can test from different locations to see how fast your visitors can access your website.

Likewise, Pingdom provides recommendations on changes you can make to increase your website speed.

Pingdom provides recommendations on changes you can make to increase your website speed.

Apart from that, Google Analytics also provides speed analysis through the page timings report. Here, you’ll see the load time of various pages. You can also compare the load time to the exit rate or bounce rates.

With these insights, you can take steps to increase your website speed.

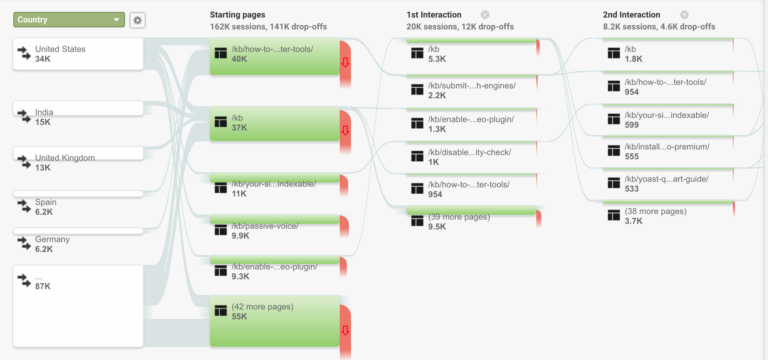

How do users navigate your website pages? With the behavior flow, you can see how visitors move from one page to another.

Also, an important data point to look out for is the entry and exit pages. Usually, the homepage will account for most entries. But apart from that, what other pages account for entries?

You can use the “Behavior Flow” feature in Google Analytics to see how visitors navigate your website. Apart from viewing entries and exits, drop-offs are a vital metric.

Use the “Behavior Flow” feature in Google Analytics to see how visitors navigate your website.

What pages have low or high drop-offs? You can continue to investigate these pages and make necessary changes to increase conversions.

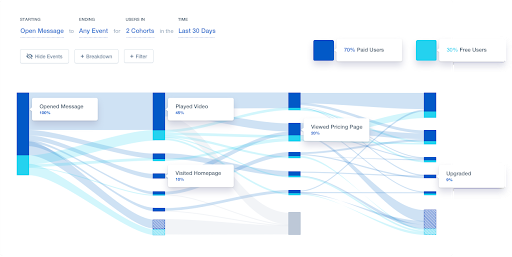

Mixpanel also provides the “Flow” feature that shows how your customers navigate your website. The conversion rate flow lets you see your conversion rates and how different criteria affect results.

Mixpanel provides a “Flow” feature that shows how your customers navigate your website.

You can see the top paths to conversion which displays your most effective marketing campaigns.

If you run an eCommerce business, cart abandonment is one constant nightmare. Think about it; the average cart abandonment rate from 33 studies is 69%.

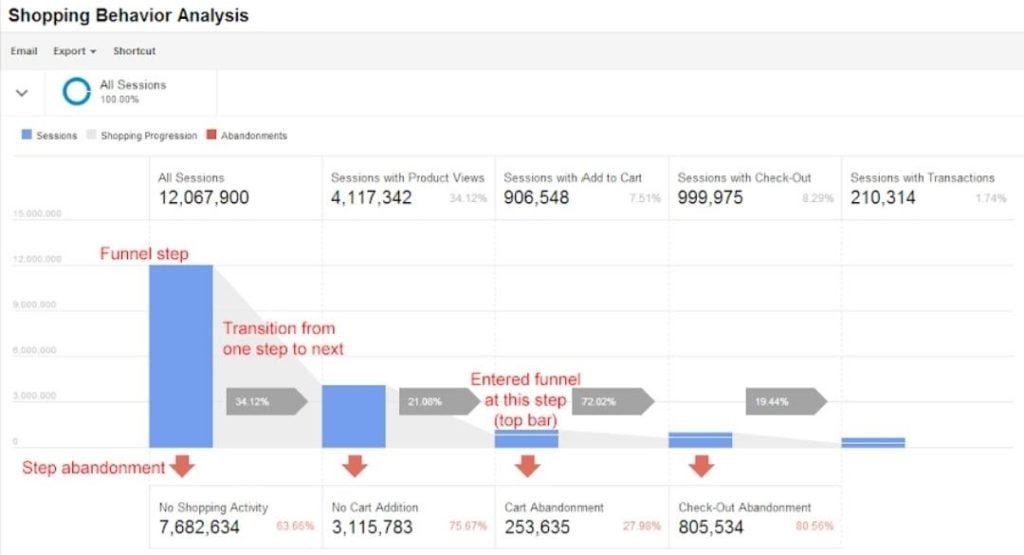

Therefore, you need to optimize your checkout process. The shopping behavior analysis in Google Analytics provides details about the number of sessions in each page of the buying process.

With this, you’ll see where visitors drop off during the buying process. Furthermore, it becomes easier to identify pages that need urgent attention.

The shopping behavior analysis feature in Google Analytics provides details about the number of sessions in each page of the buying process.

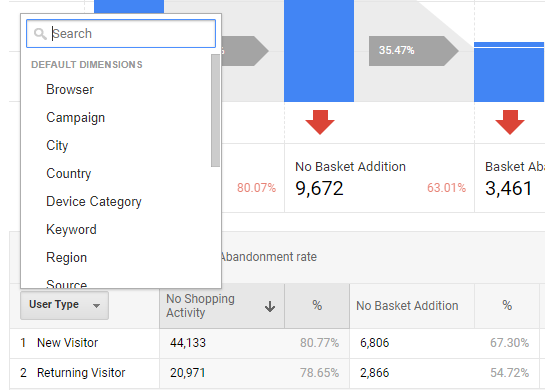

However, it’s difficult for these numbers alone to provide the full picture. For instance, do visitors from a particular traffic source account for the majority of drop-offs?

To analyze the problem further, you can create segments of traffic to these pages, such as:

After doing this, you’ll get a clearer view of the factors responsible for the drop-offs. Also, you can investigate those pages to make necessary adjustments.

Get a clear view of the factors responsible for the drop-offs.

One of the most important tasks for improving conversion rates is carrying out A/B split tests. And it’s a continuous task if you want to increase conversion rates.

While analyzing data of different pages on your website, you also form hypotheses. These are changes you can make to improve conversion rates.

For instance, you can change page elements such as:

How do you validate or invalidate these hypotheses? A/B split testing. However, to run proper A/B tests, you need the right tools.

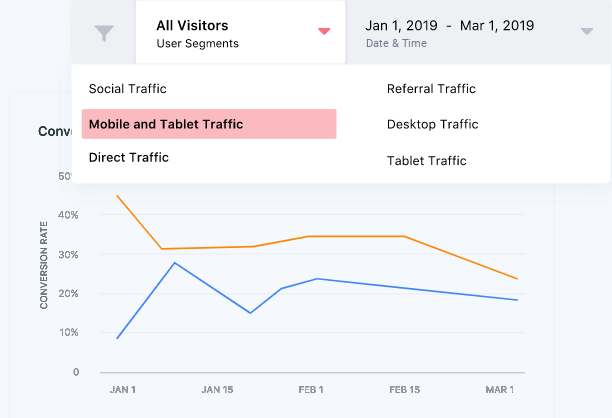

A tool such as VWO can help to run different types of A/B tests. At the end of your A/B tests, you have access to your results. Furthermore, VWO allows you to segment your results based on user segments.

A tool like VWO will show you how mobile and tablet traffic convert compared to the average. These insights would help improve your conversion rates and set up future tests.

For example, how did mobile and tablet traffic convert compared to the average? These insights would help improve your conversion rates and set up future tests.

Conclusion

Today, there are so many numbers that provide a clear picture of your website performance. However, the major challenge is to find the right numbers and interpret them effectively.

By following the steps here, you’ll gain more insights into your conversion rates and possible actions to take in future campaigns.

The post How to Increase Conversion Rates With Web Analytics appeared first on Content Marketing Consulting and Social Media Strategy.

About two-thirds of the way through The Snare, Elizabeth Spencer’s seventh novel, the protagonist, Julia Garrett, has the following exchange with her uncle, Maurice (who speaks first):

“Don’t let the past pile up, darling. It’s bad, but it’s gone and we can’t help it. Think of the wake of the boat.”

“Oh, no, that won’t work . . . it’s all around . . . around. . . .”

The line is quintessential Julia, whose every word seems matched not just to the present moment but to a personal inquiry or revelation. In this scene, she is specifically grieving the sudden death of her former lover, a wealthy (and married) Mississippi man named Martin. More broadly, though, she is articulating the root of her existential problem—the thing that, in the course of 400 pages, carries her to the brink of self-destruction—which is that Julia cannot, perhaps does not want to, escape her traumatic past.

Spencer’s gift for characterization reaches enviable depth in The Snare. On the surface, Julia Garrett is a society girl who pursues fulfillment in the seedy underbelly of post-war New Orleans. But this overarching plotline is anchored by the protagonist’s interior turmoil, which is both nebulous and rife with conflict. We spend a lot of time in Julia’s head, reflecting on her past and watching her cobble together abusive events with survivalist instincts. Chief among her preoccupations—what prompts her routine flashbacks and uncertain streams of consciousness—are her abandonment by her father and her relationship with her great-uncle and Maurice’s father, Henri “Dev” Devigny.

Though long dead at the start of the book, Dev is the subject of Julia’s love and revulsion, the figure who inspires her to consider herself both a vibrant, sensual “creature” and a whore. For Julia, Dev is “a constant heavy sun along the horizon of her spirit self,” both illuminating and blinding, comforting and oppressive. The implication is that Dev sexually manipulated Julia from the age of six, but Spencer never states this explicitly. Rather, she hews to the intimate third-person perspective that dominates the novel, an authorial choice that creates narrative tension and feels authentic to the way many women process sexual trauma. Julia cannot name what happened to her, so Spencer resists rendering it in categorical terms.

Spencer, who died in December, at age 98, had a penchant for writing characters who are concerned with their pasts. Frequently, they conduct themselves within their own historical contexts, recalling family sagas and ancient grievances amid ordinary affairs—an engagement party, a Christmas pageant, a vacation in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Often, they are Southern, reflecting Spencer’s own heritage as a native Mississippian, and as a person who, like me, was born into a cultural obsession with bearing and unravelling legacies. Early in her career, critics likened her to Faulkner, though she resisted the comparison, citing her subject as the sole similarity. In 1989, she told The Paris Review, “If my material seems like his, as I say, it must be that we are both looking at the same society.”

When she left the South—for Italy and, later, Canada—her fictional landscapes shifted, too, though her interest in familial burdens and societal constraints remained constant. For some readers, it was this focus that cemented her as a next-generation Faulkner. Others saw glimmers of Henry James in her tales about Americans abroad. As I make my way through her astonishing body of work, I find myself thinking most often of her friend Alice Munro, so penetrating is her insight into female experiences of complex class structures and rigid social mores.

And yet, despite the fact that her name often appears in grand company, and despite her prize-winning canon that includes nine novels, a memoir, and six collections of short stories, Spencer is largely overlooked in contemporary literary circles. Her best-known work is The Light in the Piazza, a novella she published in 1960 and later called her albatross. “It probably is the real thing,” she said. “But it only took me, all told, about a month to write, whereas some of my other novels—the longer ones—took years.”

The Snare is one such novel. It was published nearly five decades ago, but I first encountered it late last August, while entrenched in a reading cycle that seemed pulled from a graduate seminar in #MeToo-era literature. Piled with books like Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise, Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, and Julia Phillips’s Disappearing Earth, my desk signaled my devotion to contemporary examinations of gender and power. In this sense, I was primed to appreciate The Snare as a significant book, one that explores female identity with nuanced precision, and one that captures the messy and prolonged impact of sexual trauma. Immediately, I was drawn to Spencer’s deep exploration of Julia Garrett’s psyche and the way she wields narrative ambiguity to convey the detachment and confusion with which many women internalize abusive events. For all the broadening of conversations around sexual violence that has occurred over the past two years—for all the brilliant books I’ve consumed that deal explicitly and painfully with the subject—I am aware that navigating the aftermath of such a trauma is confusing and, often, intensely private. As she considers the qualities that separate her from her upper-crust society and propel her toward an electric yet dangerous and ultimately violent lifestyle, Julia Garrett struggles in isolation to understand her past. It is not surprising that Dev finds his way into her tortuous musings. “What was it Dev, the old man, had said?” she thinks, at one point. “‘Passion is what you’ve either got or haven’t got. . . .’ Out of such scraps she had stuck her own truth together.”

Her trauma exists in the backdrop of her quest for self-actualization, an honest reflection of how many women move through their lives.

In many ways, The Snare is a feminist novel, far ahead of its time in its handling of female sexuality and desire, as well as the influence of early and unwanted experiences. Among works aimed at deepening mainstream discussions about sexual exploitation, it becomes essential reading; but one cannot claim the subject as the book’s central concern. Probably, this is why I like it so much. What occurred between Dev and Julia slinks through her mind, never revealing itself as a certain memory and yet never receding completely. Her trauma exists in the backdrop of her quest for self-actualization, which strikes me as an honest reflection of how many women move through their lives.

It is worth noting that what is so potent to the contemporary reader barely registered with the book’s initial critics. One needs only a cursory grasp of cultural history to imagine why. The Snare was first published in 1972, a year before the term “domestic violence” entered the American lexicon, and two years before Barnes v. Train attempted to tackle workplace power dynamics. Issues of child sexual abuse hardly resonated in the public consciousness and would not garner substantial legal attention until the enactment of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, in 1974. Spencer’s novel incorporates these themes to varying degrees, usually with the type of subtle probing that suits the introspective Julia. Specifically, Spencer’s deliberate blurring of Julia’s past trauma elicited confusion among reviewers in an era when American’s had, at best, an inchoate appreciation for the sexual autonomy of women and girls.

The novel received a lackluster review in the New York Times and a misogynistic one in Kirkus Reviews. (What the Times described as narrative complexity Kirkus labeled as melodrama, declaring that The Snare was not far removed from “Southern belle lettres.”) The Georgia Review picked up on the necessity of Spencer’s painstaking attention to her protagonist’s history and interiority—elements the Times alternatively described as “the novel’s most damaging flaw”—but determined that the structure was too elevated for the book’s thematic content. This, too, has a sexist ring, considering the great extent to which female desire propels the storyline.

Spencer’s deliberate blurring of Julia’s past trauma elicited confusion among reviewers in an era when American’s had, at best, an inchoate appreciation for the sexual autonomy of women and girls.

Among these pieces of criticism, what was largely agreed upon was the plot. In great or spare detail, each described the events of the book in a similar fashion: Julia Garrett, the adopted niece of Maurice and Isabel Devigny, a respectable New Orleans couple, is tired of her well-bred lifestyle. She seeks excitement with Jake Springland, an aspiring musician and somewhat ambivalent disciple of a religious zealot. With Jake, Julia enters a world of late-night jazz shows and drug dealers and, soon, murder. The novel begins in the 1950s and spans at least a decade, thrusting a clash of societal standards into the backdrop of Julia’s experience. (Her roommate, Edie, a girl from “some dusty little dried-up town,” is her prudish foil.) Julia is, as the book’s title suggests, resisting the snare of the stifling and polite realm in which she was raised; but she is caught nonetheless by a confluence of her own impulses.

The preeminent Spencer scholar, Peggy Prenshaw, further elucidated the central themes of The Snare in 1993, when she wrote an introduction to the book on the occasion of its paperback release. “Julia Garrett,” Prenshaw writes, “seems a misfit, a woman enlivened by sexual experience and nearly destroyed by it, a woman bored by status-seeking and acquisitiveness, whose indifference brings her to the edge of hunger and homelessness.” She goes on to explain that the novel’s setting in New Orleans mirrors Julia’s seductive power and dueling instincts. Like Julia, Prenshaw says, the city is steeped in manners and tradition, but beneath its glossy exterior it is an exotic, indulgent place.

Prenshaw also references the novel’s mixed critical reception, noting the issues reviewers had with narrative ambiguity, but she does not fully explore the resonance of this authorial choice with the book’s violent plot points. Spencer’s rendering of Julia’s darkest moments is frenetic and fragmentary, allowing certain mysteries to rest in the reader’s mind as uncomfortably as they do in Julia’s. In these scenes, the events are clear, but their details are often foggy, punctuated by an image here, a sensation there. We see, for example, the flash of a blade held to Julia’s neck and glimpse, through euphemistic language, the shame she associates with what follows. As in, “After that . . .” and “I’m just going to call it an awful headache.” For Julia, what is contained in the words that and it is unspeakable, even as it holds dominion over her identity.

Crucially, vagueness distinguishes Julia’s memories of her relationship with Dev. Speaking of her protagonist in 1990, Spencer said, “Her early experience with her guardian mentor, . . . a French Cajun man who may or may not have seduced her, had a profound effect on her.” Prenshaw interprets this effect decisively. “The indisputable fact seems to be that Julia does not regard the relationship with Dev as injurious. If corrupting, it was a necessary and inevitable introduction to the ‘crooked world.’” This statement aligns imperfectly with my own impression, because it ignores the yearning that is so critical to Julia’s idea of herself. She does not want to regard the relationship with Dev as injurious. She wants to imagine it as inevitable.

Spencer makes clear that, for Julia, it is easier to live with a terrible thing when it is remembered indistinctly. Julia’s past with Dev haunts the novel because it is essential to how she views herself, and yet she is unable to define it. Violence and sexual exploitation pervade her adult life, too, and yet she never names it as such. Rather, she absorbs it all with a pronounced detachment, as though each experience is the logical conclusion of who she is in the world. After the doctor for whom she briefly works as a receptionist chases her around the office, she thinks: “. . . life was more peaceful than not with him, now that he’d made his pass.” After Jake Springland, her musician boyfriend, rapes and beats her, she thinks: “Why didn’t I find somebody good?” and then concludes that “she hadn’t because she hadn’t wanted to.” She is kidnapped twice, thanks to her association with Jake, and subjected to torture. After the first time, she thinks: “It was something in me . . . Something that wanted to go down forever, to hit the absolute muddy bottom where there’s nothing but old beer cans, fishhooks and garbage.” After the second time, she thinks: “She would gladly live like an animal, simply, instinctively, for the day only.”

Julia’s enthusiasm for New Orleans and its various vices—her sensual and subversive nature—is palpable and seemingly within her control. From the start she is an intelligent woman who knows her sexual power. But as we navigate the conflicting aspects of her mentality, we learn that her empowerment is marked by shame. At times, she reduces herself to her sexuality. Dressing for a courtroom gallery: “Might as well try to de-sex herself, she thought, as stamp out her natural looks.” Her early sexualization by Dev forms a critical aspect of her identity and self-worth, convincing her that she is incongruous with anything virtuous. She thinks, “The idea of goodness beckons forever to those who can’t have it, but once they catch up to it by luck or accident, they immediately feel uneasy, restless, miserable.”

This vivid interiority is what is largely missing from any summary or critical analysis of The Snare. How Julia decodes her own experiences is a vital aspect of the novel that seems only to have puzzled reviewers in 1972 and failed to thoroughly engage scholars in the following decades. I only learned of the book because several people recommended it to me. Each had read my work and assumed I would appreciate Spencer’s meticulous characterization of Julia Garrett. But at some early point in my first reading, Julia began to resonate as more than a technical feat. We are wildly different people, and yet I identify with her tendency toward self-examination through imperfect recollections. I possess the kind of memory that blurs even the recent past. It recalls the worst things dimly and everything else with rosy nostalgia. This has the effect of making me suspicious of my negative or painful emotions. I am unskilled at relaying the detailed origins of my deepest wounds without a large amount of ambiguity. Spencer captures this deficiency, too. After Jake assaults and abandons her, Julia says, “I don’t think I was even born a virgin.” Her effort to make sense into the plainly nonsensical seems to me like an inherited impulse, something derived from generations of cultural stagnation around gender-based violence.

Months before her death, I spoke with Elizabeth Spencer over the phone. She talked about the months she spent in New Orleans, researching the novel’s setting, and recalled her use of narrative ambiguity as the deliberate choice I had assumed it was. And yet, I absorbed from her a sense that her fixation on Julia’s past diverged from my own. “I don’t spend too much time psychoanalyzing,” she said. I felt somewhat disappointed by her answer, at first. So much of Julia’s persona appears drawn from an intellectual understanding of the functional ways in which human beings process trauma. But maybe Spencer’s more intuitive approach is what accounts for her novel’s brilliance. Perhaps her resistance to determining direct cause and effect is what allowed her to craft such a complicated and authentic character. Julia is not whittled into a particular set of psychiatric ailments, and her interior current is rich and evolving, never cyclical, never wholly diminishing. Spencer allows her protagonist a limitless quality, that of a woman constantly interpreting and reinterpreting her place in the world through her experiences. Who among us isn’t?

The post The Past Is Present in ‘The Snare’ appeared first on Electric Literature.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/TheWritePractice/~3/5l-R5iv46HU/

Writing is a lot of work, and there are definitely parts of the process that aren’t fun. But if writing has become a drudgery, if it’s become something you dread every day, then maybe it’s time for a little play to reinvigorate your love for writing. What if you were writing for fun?

I’ve spent most of my teaching career with high school and college students, but I had the opportunity to work as an elementary librarian for a few years, running book and writing clubs and basically playing in the literary sandbox with kids. It was a blast.

The kids who came to my book and writing clubs embraced the experimental in their work, willing to play with words in a way I’d not seen in the majority of my teen and adult students. I remember a student who would read the same line or page in a book with multiple voices, each one adding a new line or slightly altering the message and tone until we couldn’t hear his voice anymore over our laughter.

It was pure joy.

As I went back to my high school and college classrooms, I found that most of my students loathed writing. If I announced a writing project or exploration, it was met with groans. The questions that these writers asked included, “How long does it have to be?” and “Am I done?” Writing had become pure torture.

Somewhere along the way, someone made them feel like they weren’t writers. They stopped trusting their own creativity and voice.

As I began to unpack why, most reported that all the fun had been drained out of writing with uninteresting prompts and five-paragraph essays. They didn’t have time or the option to write about things that interested them. Too often we prioritize academic niche writing at the expense of every other form that we consume and enjoy daily.

My first goal is always the same: help them rediscover their voice and ability to play with language. Put another way, help them rediscover writing for fun. I gently nudge writers toward topics and forms they like, in hopes they would rekindle some of that childhood curiosity and creativity. We begin to see pages in notebooks filled where blank lines had once sat hopeless.

Invariably, I begin to hear conversations that include, “Listen to this!” and “OMG, I’ve never written this much before.”

A few students still eye me warily, sure I’m about to force them to turn their fun into something they’ll dread. Instead, we find the lines that sing, we find one thing to improve, and we keep going.

Volume and deliberate practice yield results. And the way to more volume? The way to keep going? Is to make the writing practice fun.

That’s fine and well, you might say, but what about the *serious writing*? I teach that too, but students need freedom in topics and form as much as possible. And I would argue that *serious writing,* like all good writing, is created from a place of fervency (some call it exigence)—the topic matters, and the form rises to meet the needs of the writer and the audience.

But don’t underestimate the power of play. We don’t outgrow it.

My college classes are finishing an argumentative writing course right now, and their culminating project asks them to engage a form creatively that uses the same skills we applied to formal academic writing: research, curation, analysis, and synthesis.

Some students are analyzing true crime podcasts. Others are building public service announcements. Some are writing fiction and others are honing creative skills like learning a complex piano piece and tracking development.

I’ve heard comments such as, “I hadn’t thought of this as writing!” and “I can’t believe I get to do this for school. I’m learning so much. Thank you!”

Turns out the best way to take your writing seriously is to play.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

How do we do it, then? Is it really as simple as, “OK, today I’m going to play”?

For kids, it is—they don’t think so much about the rules and what sells and what’s expected. If you’ve ever played a game with a child who was improvising the day as she went along, you’ve experienced this.

For adults, I’ll wager we’re all sitting at our laptops trying to force ourselves into some childlike state, fingers poised over the keyboard. “Play, darn it! Write for fun!” Really, we need to start by letting our minds wander.

What games did you love as a kid? Make a list or describe a game the way you remember it. Then write a variation.

Add something absurd. Add an alliterative line. Smile as you write or type.

Take a snack break. Smell something near you and describe it to your dog.

Read something that makes you laugh. Read something that takes your breath away. Describe what happened or mimic the form.

Don’t think about what you’re going to do with the writing that emerges. Just play. The experience is its own reward.

Do you have a child age 7 to 14 whom you would love to see keep their writing joy and develop it this summer?

We’ve gathered a group of bestselling authors, professional writers, and award-winning teachers to create a fun, interactive, week-long writing experience.

Camp sessions are all held online, and we combine the right blend of writing instruction, encouraging feedback, and lots of writing fun for kids.

During your child’s Write Summer Camp experience, they’ll get to:

We’re inviting kids ages 7 to 14 to play with writing this summer. Sound like fun?

No matter your age, you can always rekindle the joy of play in your writing. Relax and give yourself permission to be silly. Let your curiosity and whimsy guide you.

Remember, the more you write for fun and enjoy the process, the more others will enjoy reading it!

When have you found joy in writing? What are your favorite ways to play in your writing? Share in the comments.

Take fifteen minutes. Make a list of your favorite childhood games or describe a game the way you remember it.

Then write a variation. Add something absurd. Add an alliterative line. Smile as you write or type. Take a snack break. Smell something near you and describe it to your dog.

Alternately? Just sit on the floor and tinker with something for ten minutes, and then come back and describe the experience.

Share your play in the comments below, and be sure to leave feedback for your fellow writers!

The post Writing for Fun: A Guide to Playfulness for Serious Writers appeared first on The Write Practice.

Sooner or later, every short story writer comes across a list of writing pitfalls that are considered narrative poison. Include these elements at your own peril, you’re warned. But at Writer’s Relief, we know that many of these rules are not chiseled in stone—some are actually the literary equivalent of urban legends. While we can’t help with the alligators living in NYC sewers, we can help debunk a few short story writing myths. In fact, you might want to try a few of these short story no-nos when you’re writing!

No Adverbs!

At some point, every writer has heard some variation of “don’t use adverbs; use a stronger verb.” And it’s not necessarily bad advice. “She sprinted to the door” is a stronger phrase than “she moved quickly to the door,” and readers would much rather hear what he “shouted” than what he “said loudly.”

So when would we use adverbs? That’s simple: when they have something to add. “He smiled widely” could be replaced by “he grinned” or “he beamed,” but “he smiled mournfully” changes the context of the action entirely. When you use an adverb, it shouldn’t just modify your verb—it should modify the way your readers understand the action.

No Simple Words!

Is there a better word for what you’re trying to say? Well, maybe. Some words can tighten up your writing by conveying more information at once, but they also require more work from your reader. Your protagonist’s love interest may be pulchritudinous, but not everyone will know what you’re saying. And if readers have to jump out of your story every five minutes to consult a dictionary—you’re going to quickly lose your audience.

Using simple, plain language can be more effective. After a harrowing chase, your secret agent sits on a cliff watching the sunrise with her son. She’s experienced a lot of complicated emotions in the last twenty-four hours, and now that the danger has passed, she can finally relax. You could say she’s ecstatic or relieved or hopeful, and those would all be true. Or you could say she’s happy, which encompasses all of that and more. In cases like these, you can make use of a simple word’s non-specificity to invite your readers into the story and let them take it in the direction that makes the most sense to them.

No Irrelevant Dialogue!

Dialogue can be tricky, even for established professional writers. If you try to mimic real-life dialogue, you may find that your characters quickly get offtrack and your plot stalls. While trimming down your first draft, it may be tempting to cut all the lines that distract from the main plot of your story—but that’s not always the best idea. Idle dialogue can be a good way to explore other aspects of your story, like character and setting. Letting your detectives discuss their home lives may not help them find the murderer they’re searching for, but it might inform the audience on why this case is so personal for them. Too much irrelevant dialogue can bog down a story, but before you start deleting, try broadening your idea of what makes dialogue relevant.

No Large Casts of Characters!

Ensemble casts are often a tough sell, especially in a short story where you’re limited to 3,500 words or so. The more characters you have, the more perspectives there are for both you and your readers to keep up with. It’s easier to keep your cast as small as possible—but is it always better?

That depends. Each character has their own perspective and can offer you some flexibility in telling your story. But make sure you’re not including characters who don’t add anything important to the plot.

No False Starts!

Short story writers get lots of advice about beginnings. According to various experts, you shouldn’t start with dialogue, or with a description of nature, or in medias res (in the middle of the action), or any number of other ways. It almost makes you wonder how you ARE allowed to start your story!

Guess what? Any of these “no-no” beginnings can be done quite well. The purpose of the beginning is to introduce the primary characters and a conflict. A few snappy lines of dialogue that lead into a description of a problem your character is facing can do a lot to grab your readers’ interest and pull them into the story.

No Overused Plots!

After the Twilight series was published, a swarm of writers tried to cash in on that cultural explosion with their own vampire romance novels. The market became oversaturated quickly, and it’s become almost taboo to pitch that type of plot. So should you never try to copy what’s successful in the market?

Not exactly. Drawing inspiration from contemporary releases can be a good strategy! The trick is to include your own twist on the idea. Instead of writing the next iteration of Bella deciding between Eddie and Jake, maybe this time your protagonist leaves both of them and chooses a third option. Or maybe she doesn’t need a love interest! It’s up to you—take the original inspiration and make it uniquely your own.

No Clichés!

This writing advice is almost a cliché itself. Every writer has to produce something original, so they shouldn’t draw on this pool of overused phrases and concepts, right? Not always! “Cliché” is really just a fancy writer term for a shortcut. The readers understand what you want to say because of how the phrase has been used in the past.

Overuse of these shortcuts might make the reader feel cheated, as if the writer didn’t put much effort into developing the idea. However, clichés can be useful for filling in your background. If your character states it’s raining cats and dogs, your readers immediately know that it’s a downpour, not a drizzle. Using clichés can also give quick insights into the character using the phrase. If your hero responds to bad news with “when life gives you lemons, make lemonade,” your readers will see him as someone who always tries to make the best of a situation, rather than someone who’s easily discouraged. In a short story, sometimes it’s helpful to say more with fewer words.

It’s always a good idea to try different techniques when writing a short story. However, the warnings about these styles and devices aren’t worthless. All of the techniques we’ve mentioned here require special attention to ensure they’re being used correctly—if you’re not careful, they could make your story sound dull, hackneyed, and simplistic. But when used well, these no-no’s might lead to a literary editor accepting your short story submission with a Yes! Yes!

Question:Which of these no-nos do you ignore?

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/markgrow/~3/bXmGCdxMUJ0/

Business leaders and economists are forecasting dire post-crisis economic projections — perhaps the worst downturn of our lifetime. Certainly, the rapid bounce-back of the “V curve” seems improbable at this point.

But I’m not as bearish as many others for a simple reason. Economists can’t account for ingenuity.

The government isn’t going to bring us through this crisis. Politicians (at least in the U.S.) are more concerned about holding their seats and creating slick TV sound bites than leading us.

But businesses will step up to figure this out. It’s already happening.

The day New York Governor Andrew Cuomo made face masks mandatory, I started seeing Facebook ads for Pittsburgh Steelers face masks. My favorite team. On my face. Boom.

Go America.

“Every tech entrepreneur that I know is spending time on the pandemic response,” CEO of global start-up accelerator The Founder Institute Adeo Ressi told CNBC. “Many innovations will result from this global focus.”

Robert Herjavec of “Shark Tank” fame said the entrepreneurial spirit of America makes him optimistic about the U.S. economy despite the post-crisis economic projections.

“The human condition is about hope,” Herjavec said in a TV interview. “Every time someone comes on ‘Shark Tank,’ they’re full of hope and they’re full of optimism. This is a challenging time but entrepreneurs will figure it out.”

Another one of my Shark Tank favorites, billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban, is adamant that capitalism and Americans’ entrepreneurial spirit will fuel an economic rebound that will birth several “world-changing companies.”

In an interview, he said, “The one thing about the United States of America that’s different than every other country on the planet is that we’re a country of entrepreneurs. We look to start businesses. When we talk about the American Dream, when we talk about rags-to-riches stories, it starts with an entrepreneur coming up with an idea and executing on that idea.”

Here are a few examples of businesses rising up to meet the needs of the coronavirus crisis in inspiring ways!

Reading through these little stories helps you see the incredible potential of the entrepreneurial spirit. And that’s why I’m not dismayed by the post-crisis economic projections.

Coming out of the Great Depression, 9/11, the World Financial Crisis, the projections were uniformly dire — and wrong.

The most influential and important events are the ones that emerge spontaneously and with little warning — like the coronavirus itself. We will have millions of those events ahead of us. The innovators, creators, and makers will lead us to the other side.

America, we were built for this.

Mark Schaefer is the chief blogger for this site, executive director of Schaefer Marketing Solutions, and the author of several best-selling digital marketing books. He is an acclaimed keynote speaker, college educator, and business consultant. The Marketing Companion podcast is among the top business podcasts in the world. Contact Mark to have him speak to your company event or conference soon.

Mark Schaefer is the chief blogger for this site, executive director of Schaefer Marketing Solutions, and the author of several best-selling digital marketing books. He is an acclaimed keynote speaker, college educator, and business consultant. The Marketing Companion podcast is among the top business podcasts in the world. Contact Mark to have him speak to your company event or conference soon.

The post Why I’m not dismayed by the post-crisis economic projections appeared first on Schaefer Marketing Solutions: We Help Businesses {grow}.