http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/TheWritePractice/~3/2uc4QA8oX7E/

In life, it can feel like things happen randomly, without causation, and with little or no meaning. The human brain, though, needs meaning. We need to understand why things are going badly for us so we can avoid it or why things are so well so we can do more of whatever’s working.

This is why humans love story.

In stories, we get to see the cause-and-effect connections between otherwise random events. We get to experience the deeper meaning in life. We get to see through the chaos of real life and see the underlying pattern.

The literary term for this pattern is story arc, and humans love story arcs.

In this article, we’re going to talk about the definition of story arcs, look at the six most commonly found story arcs in literature, talk about how to use them in your writing, and, finally, study which story arcs are the most successful.

Definition of Story Arc or Narrative Arc

A story arc, or narrative arc, describes the shape of the change in value, whether rise or fall, over the course of the story.

That’s the definition, but what does it actually mean? Let’s break it down.

Story Arcs Rise and Fall

Stories change. If there is no rise or fall in a narrative, it isn’t a story. It’s a list of events.

The rise and fall of characters’ fortunes interest us more than anything else.

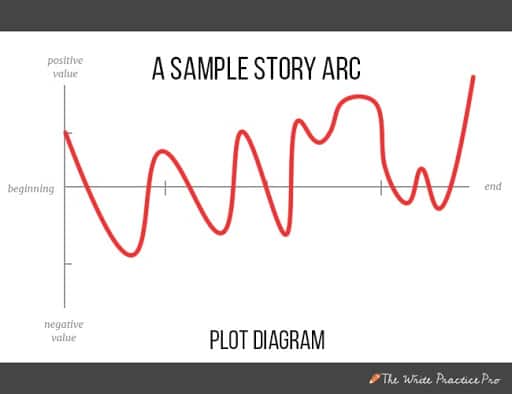

This change, the rise and fall in a story, can be plotted on a graph to form a curve shape line.

And when you graph them, you begin to see patterns across all forms of story.

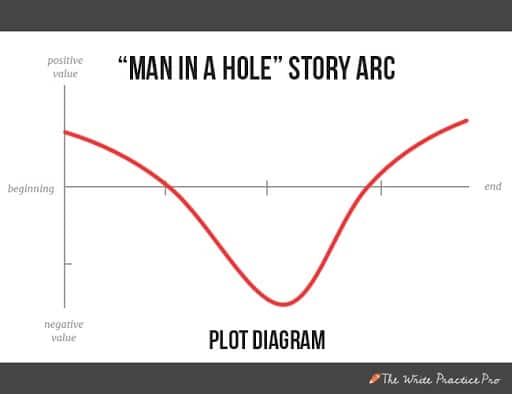

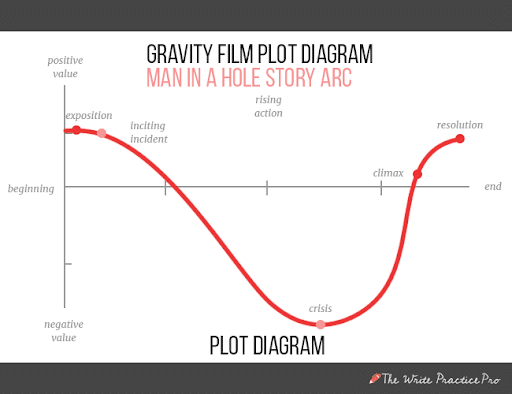

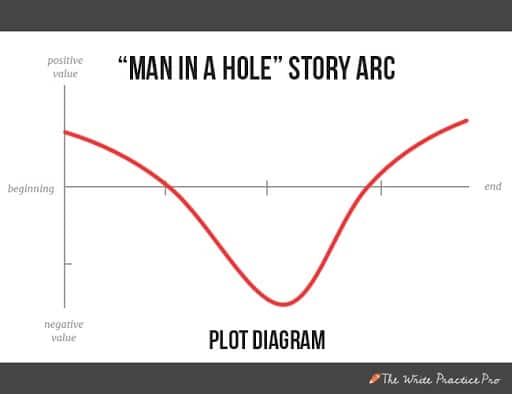

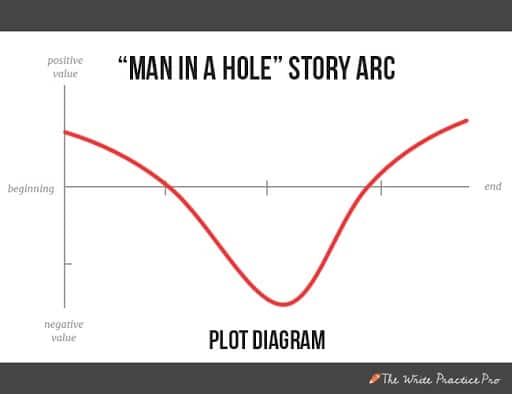

Here is a simple graph of a story arc that Kurt Vonnnegut describes as “Man in a Hole”:

The x-axis of the graph describes the chronology of the narrative and the y-axis describes the positive or negative value the main character experiences.

The 6 Primary Story Arcs

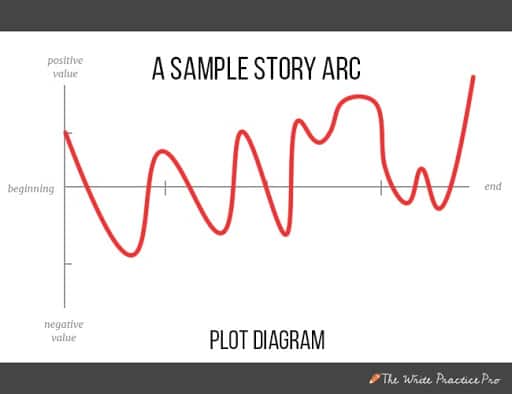

Story arcs of course do not always follow such simple graphs. In fact, story arcs can often look more like this than a smooth curve:

Yes, stories must change, but that doesn’t mean they all change in the same ways.

But when you compare the story arcs of the best stories throughout history, patterns begin to emerge, and you find that these arcs are much more uniform than you might think.

That’s what Andrew Reagan and his team of researchers from the University of Vermont found after analyzing over 4,000 of the best novels from the Project Gutenberg library.

In fact they found that stories fall into six primary arcs, which I’ll list below. You can find the full study, Toward a Science of Human Stories, here (the part we’re talking about begins on page 73).

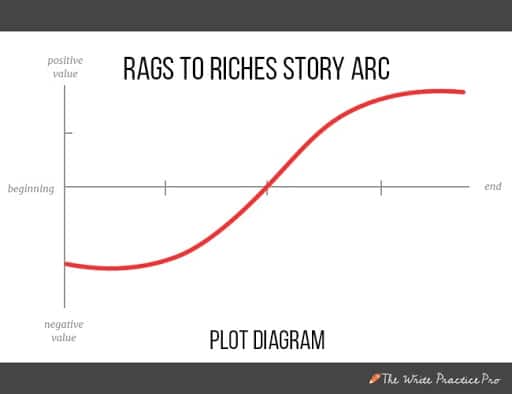

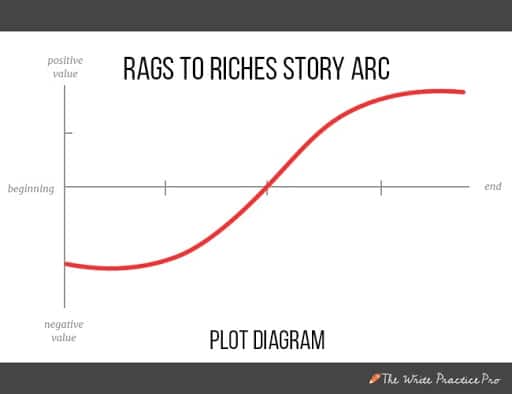

1. Rags to Riches (rise)

All stories move, but some stories only have one movement.

In the “Rags to Riches” story arc, that movement is a continuous upward climb toward a happily ever after.

Examples of Rags to Riches story arcs:

- Disney’s Tangled

- A Winter’s Tale by William Shakespeare

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Matilda by Roald Dahl

- Holes by Louis Sachar

- The BFG by Roald Dahl

- My Fair Lady (film) / Pygmalion (novel) by George Bernard Shaw

- The Great American Dream / Progress

The Rags to Riches story arc is one of the most common story types, but these stories lag in popularity, according Reagan, the researcher from the University of Vermont, who found that other story arcs were more widely read.

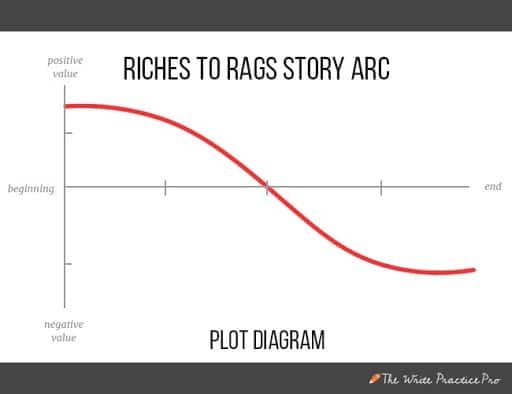

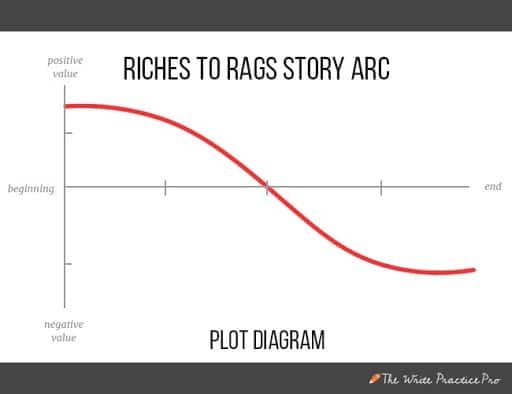

2. Riches to Rags (fall)

As with Rags to Riches, in a Riches to Rags story, there is just one movement. However, this movement is in the opposite direction, a fall rather than a rise.

Examples of Riches to Rags story arcs:

- Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

- Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

- Love You Forever by Robert Munsch

- Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

In a Riches to Rags story, the protagonist begins the plot in a fairly high place, but slowly their life devolves until by the end, their life is a ruin of its former self.

Often addiction stories or stories about mental health fit into this structure.

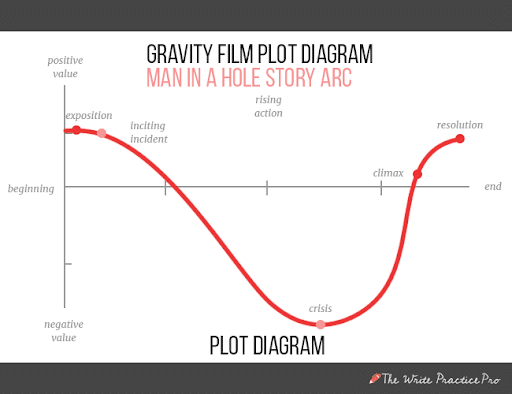

3. Man in a Hole (fall then rise)

This is one of the most common and highly rated arcs, and is even an arc I used in my book Crowdsourcing Paris.

Examples of Man in a Hole story arcs:

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

- Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

- Disney’s Monsters, Inc.

- Finding Nemo

- “Make America Great Again,” Donald Trump’s Campaign Slogan

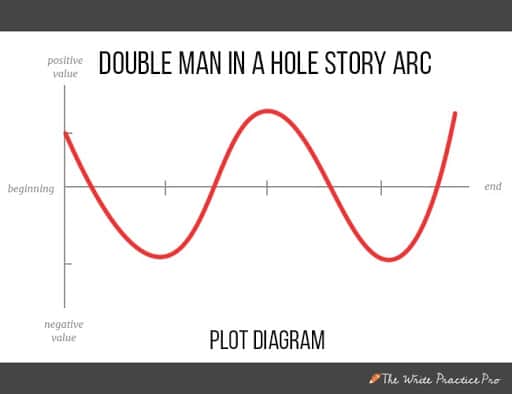

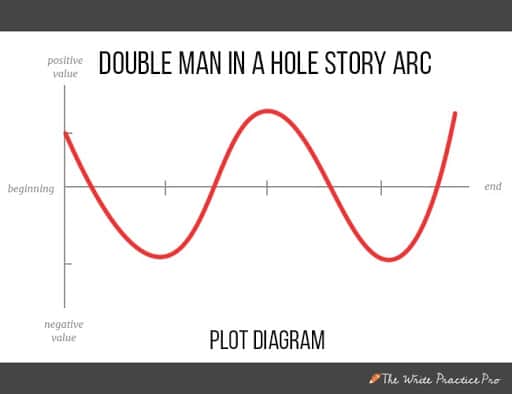

Many stories actually include two sequential Man in a Hole story arcs, as illustrated by this curve:

According to Reagan and the researchers at the University of Vermont, this is one of the most popular structures. He says in his paper:

We find “Icarus” (-SV 2), “Oedipus” (-SV 3), and two sequential “Man in a hole” arcs (SV 4), are the three most successful emotional arcs.

Examples of the Double Man in a Hole arc include:

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban by J.K. Rowling

- Disney’s The Lion King

- And more

Some stories even contain many Man in a Hole arcs—becoming Man in a Hole, Man in a Hole, Man in a Hole ad infinitum. Lord of the Rings and the 6,700-page online serialized novel Worm are examples of this.

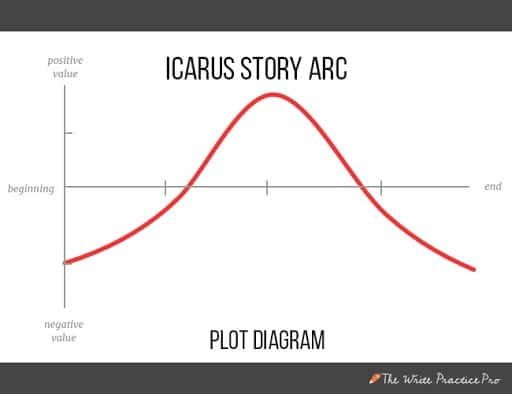

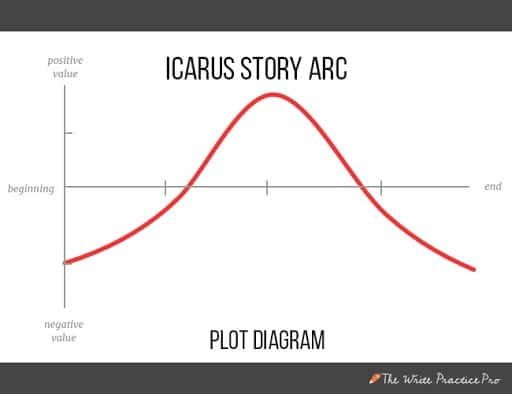

4. Icarus / Freytag’s Pyramid (rise then fall)

This is the plot structure Gustav Freytag was interested in when he coined the plot structure now known as Freytag’s Pyramid (contrary to popular belief, Freytag’s Pyramid is not a universal structure for plot, but a description of a single arc). For more on this literary concept (and how it’s since been misunderstood), see our full Freytag’s Pyramid guide here.

The Icarus arc, named after the Greek story about a boy who escapes imprisonment on an island by constructing wings made of wax but who ultimately falls into the sea after flying too close to the sun, is one of the most popular story arcs.

Examples of the Icarus story arc includes:

- Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- The upcoming novel Pluck by J.H. Bunting (me!)

- Macbeth by William Shakespeare

- Disney’s Peter Pan

- The Old Man and the Sea / A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

- The Fault in Our Stars by John Green

- Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton

- Titanic (film)

- Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- The Great Santini by Pat Conroy

- If the word “great” is in the title, you know you’re in for a sad ending! This a popular story structure with literary writers, and tends to be a staple structure for many classics.

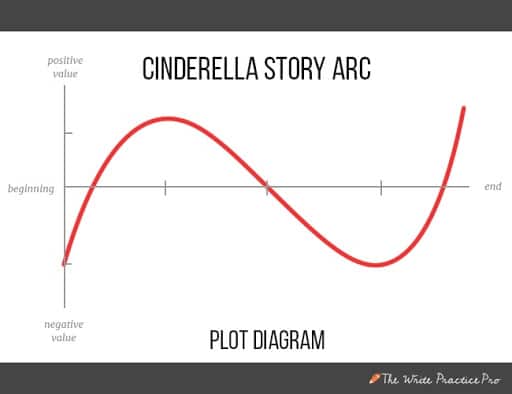

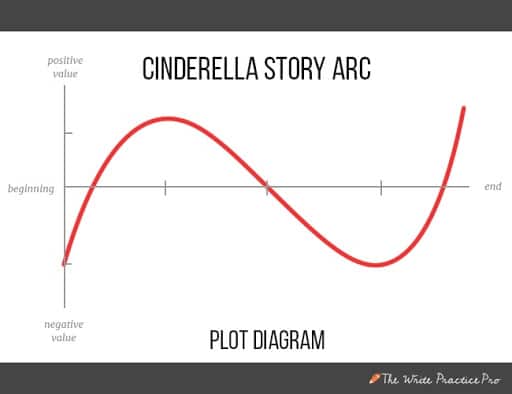

5. Cinderella (rise then fall then rise)

The Cinderella arc, like Rags to Riches, is one of the most common arcs, often found in love stories, sports stories, and Disney movies.

Examples of Cinderella story arcs:

- Disney’s Frozen

- Disney’s Up

- How to Train Your Dragon (film/novel)

- Jane Eyre by Emily Bronte

- Disney’s Pinochio

- Disney’s Aladdin

If you’re writing a Disney movie, there’s a good chance it’s going to be Cinderella.

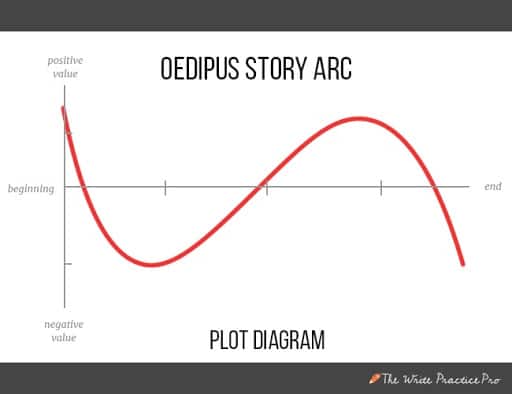

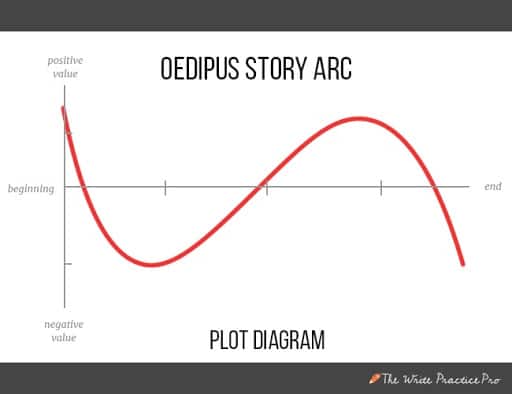

6. Oedipus (fall then rise then fall)

The Oedipus arc is of the most difficult structures to pull off, but it’s also one of the most highly read structures.

Examples of the Oedipus story arc include:

- Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie

- Lolita by Vladimir Nabakov

- The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

- Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

- The Godfather by Mario Puzo

- Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

- Hamlet by William Shakespeare

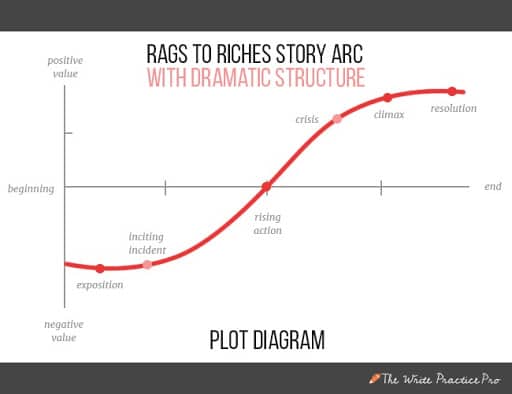

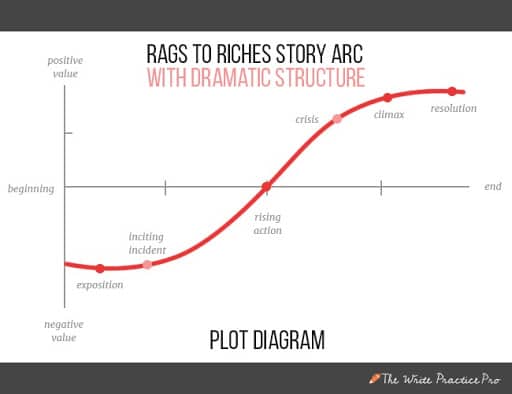

How Story Arcs Fit Dramatic Structure

Dramatic structure describes the elements of a story’s movement, and each of the above story arcs incorporates the dramatic structure. At The Write Practice, we use a six-part dramatic structure:

- Exposition

- Inciting Incident

- Rising Action/Progressive Complications

- Crisis

- Climax

- Denouement

Note that many people include the falling action in their dramatic structure. I don’t include it because I believe the term “falling action” to be misleading and really only appropriate for Freytag’s narrow definition of the tragic, Icarus structure, not a modern three-act story structure. You can read more about this in my falling action article.

Here’s how these elements of dramatic structure fit into the Rags to Riches Story Arc:

In this arc, the exposition has little to no movement and is primarily to acclimate the reader to the world of the story and its characters.

The inciting incident begins the upward movement.

The rising action describes the upward motion of the movement.

The combination of the crisis and climax is the point of the peak, the make-or-break moment when things could either continue to improve or reverse.

Last, the resolution wraps up the story at the end with one or two scenes of relative stability.

These components of dramatic structure can be found in every arc, and are part of what gives each arc their structure.

Story Arcs Measure Values

A story’s rise and fall in value can be expressed generally in terms of “fortune,” but you can also get more specific by measuring a story’s movement based on six different story values.

You’ve heard that your story needs conflict, but what does that actually mean? Because the kind of conflict stories need is (probably) not more fistfights and loud arguments (although, depending on the story, that might not hurt!).

No, the kind of conflict your story needs is between one value and its opposite.

Which values?

A good story rises and falls on the spectrum of one of six different values, according to Shawn Coyne the author of Story Grid. The six values, which follow Mazlow’s Hierarchy of Human Need, are as follows:

- Physiological. The value of food, water, air, warmth, and rest. Life vs. death.

- Safety. The value of personal and group security. In story terms, life vs. a fate worse than death.

- Love/Belonging. The value of intimate relationships and friendships. Love vs. hate.

- Esteem. The value of personal prestige and accomplishment. Accomplishment vs. failure.

- Self-Actualization. The value of reaching your potential. Maturity vs. naiveté.

- Transcendence. The value of becoming more than yourself. Good vs. evil.

The rise and fall of these values dictate the rise and fall of the arc.

For example, in an adventure story set in space like the film Gravity, where the core value is physiological survival, you would measure the arc based on this life vs. death metric.

Let’s break this arc down, analyzing the rise and fall of the life vs. death value throughout the key moments in the story:

***Spoiler Alert***

Exposition: Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and astronaut Matt Kowalksi (George Clooney) are on a space walk on the Hubble Space Telescope. Life vs. Death value measure: stable.

Inciting Incident: A missile strike causes a chain reaction of space debris that threatens to destroy much of the spacecraft around the planet. Life vs. Death value measure: A threat of death appears.

Rising action: The space debris field begins to destroy spacecraft, including Stone and Kowalski’s ship, and they have to escape to the International Space Station. But the spacecraft ISS has been damaged, and they have to travel to the Chinese space station. While en route, Kowalski sacrifices his life to save Stone. Other space shenanigans happen until Stone is out of options for survival. Life vs. Death value measure: inching closer and closer toward likely death.

Crisis: The sole survivor of the debris field and trapped in a Soyuz capsule without fuel, Stone has to choose whether to end her life or keep working to survive. Initially, she decides to turn off life support, but as she is losing consciousness, a vision of Kowalski gives her a final solution to reach the working Chinese re-entry capsule. Life vs. Death value measure: near death.

Climax: Stone reaches the Chinese re-entry capsule just as the space station is about to crash into the atmosphere. She unlocks from the station and is descending to Earth when a fire starts. After she lands safely in a lake, she has to evacuate the capsule immediately because of the smoke and nearly drowns before finally swimming to shore. Life vs. Death value measure: near death but survival becoming a slim possibility.

Resolution: Stone takes her first steps on Earth, thanking Kowalski, and as she watches the debris burn in Earth’s atmosphere, a helicopter flies overhead signaling her rescue. Life vs. Death value measure: survival by a small margin!

***End Spoiler Alert***

Notice how the story moves from virtually no chance of death to death almost a certainty to the resolution, where survival seems even more precious because of how close the protagonist came to death.

The story moves the value from the positive form to the negative, and, depending on the value, back again. The story’s arc is created through this rise and fall movement.

This same arc can be used to tell a love story, a performance story, or even a coming of age story. The arc stays the same, but the value being represented by the arc changes.

How to Use Story Arcs in Your Writing

Now that you understand the six main arcs and how the shapes of stories interact with a story’s core value, how do you actually use this information to write great stories?

Here are five tips for using story arcs in your writing:

1. Above all, make sure your story moves.

It can move up, it can move down, it can move up and then down. But it must move, and that movement must begin early.

A narrative that stays the same is not a story but an account of events.

2. In the first draft, don’t worry about matching your story to a particular arc.

You may know what your arc is when you start writing, and you may not.

Don’t worry too much about it. Just tell your story (and make sure that story moves).

3. In the first draft, do worry about finding your core value.

While you don’t need to worry about finding the right shape of your story when you start writing, you should try to discover the core value, the y-axis that your story will move on.

If you can discover your core value (see the list of six values above for the options), you will be much more equipped to making sure it moves the way it needs to.

And while you may choose more than one value—perhaps a value for a subplot or the internal genre—if you try to move your story on too many values it will become muddied and will be very hard to work with in your second draft.

Above all, keep it simple. You can always write another book, but a book that’s trying to do too much can easily become unworkable.

4. Write to the crisis.

When you’re writing a first draft, you don’t need to know everything that’s going to happen.

If you’re a pantser rather than a planner, you might not know anything that happens.

But the best thing you can do is to write toward the crisis.

The crisis is the primary turning point in a story. It is the moment when a character is presented with a difficult choice that will determine his or her fate.

This moment is usually found at the very bottom of a dip in a story arc or the very top of a peak. It will be followed almost immediately by the climax.

If you can find that crisis, you will have found your story.

Everything in a story builds to the crisis.

For more on how to discover the crisis in your story, read my full guide to a literary crisis here.

5. In your second draft, find the arc and enhance it.

While you don’t need to know the shape of your story arc in your first draft, after you finish your first draft and before you start your second draft, find your arc.

What is its shape? How does it rise and fall? Does it fall enough? Does it rise enough? Is there enough movement?

The purpose of the second draft is to enhance your arc, to make it more pronounced, smoother and more effective.

All Good Stories Have an Arc

Good stories are about change, and thus all good stories have an arc.

By finding the arc in your story, and making that arc better, you can give your readers what they want: meaning.

All humans need meaning. While the world often can feel confusing, chaotic, and meaningless, the role of the storyteller is to help people find meaning in their lives.

This is why humans love story.

And soon, it’s why readers will love your story.

Which of the six story arcs is your favorite? Which story arc do you want to use for your next book? Let me know in the comments section.

PRACTICE

Let’s practice using story arcs with a creative writing exercise. Here’s what we’re going to do:

- Choose one of the six story arcs: Rags to Riches, Riches to Rags, Man in a Hole, Icarus, Cinderella, Oedipus.

- Write a six sentence story based on that arc using the six elements of dramatic structure: exposition, inciting incident, rising action, crisis, climax, and resolution.

- Then, set your timer for fifteen minutes and expand your six sentence story as much as you can.

When your time is up, post your practice in the comments section below. And if you post, be sure to give feedback on at least three other stories.

Happy writing!

The post Story Arcs: Definitions and Examples of the 6 Shapes of Stories appeared first on The Write Practice.