The citizens of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia had a prescribed rest/nap time every working day, between 3-5 p.m. We, the children, were not allowed to play outside or make noise, there was not to be any drilling, knocking or slamming doors, and we could not drop in on each other, as was our habit.

These two hours were called ‘house order’ in the meaning of being ‘orderly’, and not ‘to be ordered’, though in reality we, the children, were ordered not to go outside. If we did go outside and make noise during the designated hours, disgruntled neighbours emerged on balconies or descended the stairs in slippers, hair messy and mouths billowing with rage. They yelled at us to go home, or threatened to call our parents, who were already napping. This was how I used to sneak out and go down to the park during house order time – I would wait until my mother and father were in their post-lunch slumber, father snoring up a storm, mother letting out brief put-put-puts of air, like a fishing boat.

I had many plastic toys, but what I loved best were the dolls my friends and I made out of discarded ice lolly sticks. We drew two dot eyes and various expressions to make different characters, and dressed them in sweetie wrappers, which we diligently collected at home, on the street or around rubbish bins. We made lunch for the little people out of crushed leaves and grass, mashing the ingredients with stones and pond water and soil. When I descended to the park outside our block in the forbidden play hours, I would play voicelessly, mouthing the dialogue between the little people. Daddy sometimes shouted; mummy shouted back. The children sat in a corner, quiet. When mummy and daddy left, the children ran around causing havoc.

I had also made a little people stick that was Comrade Tito, our country’s president and our hero. I used the Comrade Tito little people figure as an instant tranquilliser, something that made the room fill with love and justice and peace when nothing else worked. Because this reflected our real life – Tito’s image was a call to our best selves. Between us children, if someone was accused of telling a lie, it was considered worse – in our street code and hierarchy of honour – to falsely swear on Tito’s life than on our mother’s. Tita mi, was the seal of truth on anyone’s word.

*

‘I’m a writer obsessed with remembering, with remembering the past of America and above all that of Latin America, an intimate land condemned to amnesia,’ Eduardo Galeano said. Remembering, reminiscing, conjuring up, reviving is also what we, the former Yugoslavs, do; our lives, as we knew them, were yanked away from us in such a swift, violent way, we are left to turn up the soil of our memory, hoping to make some sense of ourselves through what we find. And I, like every other Yugoslav, have had to examine the veracity of my memory, of that memory. I had to look at which part of that country, that ideal, was true and good, and what was oppressive and false. And although there are varied, often opposing versions of the same historical event, one thing has persisted throughout my readings, analysis and conversations on the subject: that Yugoslavia’s ending, in bloodshed, cannot be its only legacy, the only lesson we take away from its existence. It is too one-dimensional, too easy, for Western Europe to dismiss Yugoslavia, with its ethnic hatreds, corruption and oppressive politics, as a mere example of Balkan savagery (as I once heard the Conservative politician Alan Clark describe it on BBC News).

The memory of Yugoslavia can teach the countries of the liberal West a crucial lesson in the 21st century, as fascism is once again on the rise throughout the world: that noble ideals – be they of Socialist brotherhood and unity, or of democracy – are easily proclaimed in theory, but even more easily betrayed in practice. Yugoslavia is an urgent example of how socially progressive potential is wasted when it is laid upon the old structures of supremacist, patriarchal domination. As Audre Lorde writes: ‘Advocating the mere tolerance of difference […] is the grossest reformism. […] Only within [the] interdependency of different strengths, acknowledged and equal, can the power to seek new ways of being in the world generate’. And in Yugoslavia, just like in the US, UK, EU, and the rest of the ‘developed’ democratic world (a terminology the West owns and applies as and when necessary) the social structure relied on a hierarchy rooted in inequality, domination and the preservation of privilege. The Yugoslav Socialist project cracked along lines that also exist in the imperialist, white-supremacist, capitalist patriarchies of the US, UK and the EU. The politics of patriarchal dominance, nationalism and the preservation of privilege became overt, the language of division and hatred was normalised, and the media were in the service of formalising and affirming all of those messages. Fascism and the far right are once again legitimate political options across the world – this is nothing new. Liberal democracy is a myth, just like how in Yugoslavia the concept of brotherhood and unity was a myth – because the fascist within was never rooted out. The global social unrest of June 2020 stems from the same place where most of the social revolutions – or attempts at revolutions – have come from since the end of World War Two: the struggle to right social injustice. It is meaningful that one of the most resonant ways to make a political statement in the June 2020 riots in the US has become to loot corporate chain shops – to damage the embodiment of capitalist power – because political power is in the hands of corporations, and is therefore as undemocratic in the West as it was under a one-party communist government. In capitalism, people and objects are interchangeable, and often objects (or rather, capital and property) are more valuable than human life. Violence against objects, statues and private property rattles both conservatives and liberals more than the regular, systematic violence against living, breathing human beings.

*

I grew up with the ideal of Yugoslavia, as it was taught to me at home and at school. Along with every other Yugoslav child turning seven, I swore an oath to the Union of Yugoslav Pioneers, which was a kind of communion-with-the-cause ceremony, that saw us repeat the words: ‘Today, as I become a Pioneer, I give my Pioneer word of honour, that I will work and study diligently, respect my parents and the elderly, and be a loyal and honest friend, who honours their word. That I will love our self-managing homeland, the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia, that I will spread and develop brotherhood and unity, and the ideas that Comrade Tito fought for. That I will appreciate all the peoples of the world who want freedom and peace.’ It was considered a great honour to become part of the Pioneers, and most of us took the oath seriously.

It now seems quaint and nostalgic, almost cinematic, to imagine or indeed see the photographs of us children, red kerchiefs tied around our necks and blue envelope caps with a red star on our heads, our parents proudly snapping our toothless smiles. I often think back to that oath, and I wonder what we might think now if our children said those words in unison in our ‘modern world’? Would we find it banal, embarrassing, oppressive, naive? How have we come to believe the neoliberal global narrative of abstract individual happiness, in which we search for happiness, pursue happiness, have happiness indexes? How have we adapted to and come to accept the conditions of capitalism, racism and systematic oppression, where the poor are poor because they are not working hard enough?

*

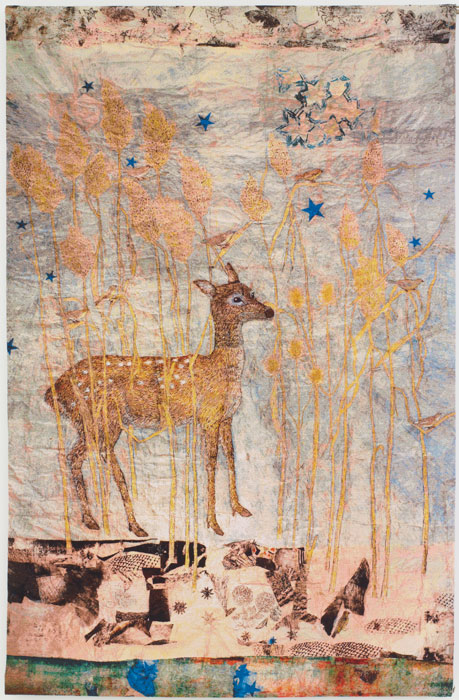

As a child I loved to lie down on the grass and watch the canopy of trees above. There was a union on my street, a love union, really, between a linden and an oak. The linden grew in a garden on the left side of the street, the oak on the right, and their branches stretched above the garden walls and bent towards each other, their leaves touching mid-air, mid-street, making an arch of pink and yellow flowers, and they perfumed the air with gentle affection. They held hands, but never went any further towards each other, for they knew that the light and the air on the opposite side was already needed and taken.

They say that trees are alive; not just in the way that can be observed, with the leaves growing and falling off, but that they are alive with families and communities, and that they are intelligent. I read this in a book. Trees, it said, work together. When they are friends, their branches grow as far as they can to touch each other, as if with fingertips.

Trees do the work of sharing naturally, while humanity seems to need steering. As a child that was the function of the mottos that were drilled into us, to teach us the value of working together – under the watchful gaze of Marshal Tito. We were often told that the first road leading into town was paved when Marshall Tito announced his first visit. Before that, the roads were dusty bare ground, trodden by mules and wooden clogs. In honour of Tito’s visit to the town, the local youths were sent to the hill above town, the hill facing the direction of the newly paved road, to spell out in white chalk rocks – dug out from the earth around the city, the rugged earth that brimmed with nothing but stone – we love you tito. The sign stood there from the 1960s until the war, where it is now written we love you bosnia and herzegovina.

Each classroom and each official space in the country had a picture of Tito on the wall. On my first day of school, as pairs of students sat in rows of desks, the teacher came in to class and announced: ‘Children. Some of you may have heard of God, and that he exists. Well, he doesn’t.’ He then went to distribute chocolate bars, one per child. No more was said. That same day, we read a story about two boys who fought over who the Tito was gazing at from one of those pictures. Each was insisting ‘me, me,’ until the teacher came up and said, ‘Don’t fight. Tito is watching over us all.’ Just like God or Santa are omniscient and omnipresent, so was Josip Broz Tito.

In his photographed presence, school children were not to wear hats, nothing that would cover their heads. We were not allowed to chew gum, because that was both rude and stank of rotten capitalism, something that lived outside of our borders and bore a fiendish mix of fascination, fantasy and loathing.

We were raised on films about brave partisans who traipsed snowy mountains for liberty and got so frostbitten that they had to cut off limbs, with nothing but homemade brandy to anaesthetise them.We bit our lips as the movie soldiers applied army knives to each other’s purple toes; this was not censored for children – it was the past we were meant to be proud of, part of the history that we were taught is solid, like the monuments that were built to honour that history. We were to understand that it is not easy to be a hero(ine), but that peace and freedom were worth fighting for, even if the price was death.

*

I was four years old the day that Tito died, and it was on the same date, exactly thirty years later, that I gave birth to my daughter. All of my family members remarked on the fact that her life was delivered into the world on the same day that our great leader’s had been extinguished, and we all took it as a good omen that she would have a strong, forthright and just character and good taste in clothes.

When she was three years old, I moved with her to work and live in Bosnia after twenty-one years in the UK. While we were in Bosnia, my elderly aunts and uncles, my mother, our neighbours, came to celebrate my daughter’s birthday. Some of them made trips across town, others across the country, for the day. They brought gifts and food and smiles and their warmth, and each time, as the evening drew its inky curtain across the sky, I listened to them reminisce about Yugoslavia. Their golden years – they had lived in Yugoslavia when it was in its prime. It was the third year of hearing the same stories – my uncle’s favourite incantation of the time Tito and his wife, Jovanka, came to the restaurant where he worked, and he served them, and I imagined his proud moustache twitching in synch with his bow tie and his Adam’s apple – that I understood that what they were doing at these gatherings was a kind of group mourning. But it was also the opposite of mourning – if mourning is meant to be followed by an acceptance of loss, a letting go and a facing of one’s reality. This was an attempt at conjuring, at remembering all that had been lost – perhaps in order to test its reality. These elderly people seemed to be both reminiscing about their lives and to be holding them up to the light of collective memory because they were not sure if they had ever really lived these lives they spoke about. They spoke of the fact that they had all had jobs, homes; how one knew what was what; the cities were well looked after; the environment was kept clean – ‘We were proud of our country!’; and how the Yugoslav passport was something you would never be ashamed to travel with. ‘Tito held a glass of vodka in one hand, and a glass of whisky in the other’, was, and remains, a common expression for the way Josip Broz handled Yugoslavia’s international relations during the Cold War. ‘Even if he embezzled money, as they say, he at least gave some of it to us, the country’s citizens – today these criminals that run the country just take everything for themselves while the country sinks deeper into poverty,’ was another oft-repeated sentiment in the post-Yugoslav years. These were the people who had fought and lived with certain convictions and values, all of which were deemed to now no longer either be relevant or true. They were the embodiment of the denied Yugoslav ideal; they remained physically in the same place where they had lived and built their entire lives, but their country – its boundaries, its population, its values – was gone, had vanished around them, and something different had taken form, something in which they no longer felt at home.

Wherever one goes inside the former Yugoslavia, one comes up against the past. It is a past that is dismembered and fragmented – what philosopher Boris Buden explains as ‘an ubiquitous past [. . .], a past that is more current than the present and more uncertain than the future. A past that everyone is invited to judge, to recall, understand and (re)create on their own, individual terms. A past that is not really a dimension of actual time, but is in fact, a cultural artefact.’

As I looked and listened to the incantations of my elderly family and friends, their bodies hunched over with the years and their heads adorned with colourful, tiny party hats that my daughter had administered to each family member to wear – which they did, dutifully – I realised that they had nothing to cling onto for their sense of reality except for that past.

Back in 1990, when Yugoslavia was apparently undergoing an ‘economic transition’, the word ‘democracy’ was bandied about with great fervour, promising a healthier, more enlightened way of living, of governing our society, making us more like the Western world. But the truth is, the ensuing war and chaos notwithstanding, the democratic process that was brought into the countries of the former Yugoslavia failed to deliver anything meaningful or progressive, landing these countries instead with neo-colonialism and the harshest aspects of capitalism.

Yugoslavia had free housing, and housing came with a job. There was very little private property and the land belonged to the country’s citizens. There was free healthcare and free education. The economic order was based on the workers’ self-management model that aimed at a democratic approach to labour practices. The infrastructure of the country – roads, railways, river dams etc. – was built through youth volunteer actions. The literacy rate went up to some 80 per cent from what was a largely illiterate population. Yugoslavia was one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in 1961, a movement of the so-called Third World, which stood as an alternative to the countries locked inside the Cold War division; it was a peaceful movement consisting of the newly independent, post-colonised countries across the African and Asian continents (it still exists, but is now largely ignored). Yugoslavia was its only European member. As a region that had been colonised for centuries – first by the Ottomans then the Austro-Hungarians – and whose first incarnation was a monarchic union with a massively impoverished, peasant population, it understood only too well the importance of maintaining its independence from the imperial powers of the political East and West. The Yugoslavs could travel freely, and many worked abroad, across Africa and Asia. Equally, students from African and Asian countries in the NAM came to study in Yugoslavia. Back in 1997 I came across a Sudanese man in London who spoke fluent Serbo-Croat. He recalled his days as a student in Belgrade with joy; to me it seemed impossible that anyone foreign might live there again, save for the well-paid aid worker. ‘Why did the war happen?’ he asked.

*

Why did it happen, indeed? In the Bosnian Oscar-winning film No Man’s Land, one of the jokes in this war comedy is about the perennial question ‘Who started the war?’ The joke, I think, is that it is a question with no real answer, or that it has many answers, depending on whom you ask. In other Bosnian jokes regarding the beginnings of the war (for later on it was hard to find anything funny at all), there were always references to a group of friends making claims about the superiority of their own ethnic group, each claim being more banal than the other. And indeed this reflected real life: in my own family and school, with the sanctification of nationalist, fascist rhetoric, adults and adolescents extolled their own national group over the rest – but always over one in particular (Serbs against the Albanians, and the Bosniaks, Croats against the Serbs, etc.). People one had previously shared a perfectly reasonable time with started to make statements about their historic supremacy, the dirt and unkemptness of the other, their many children, and the rest of the racist tropes that are always in good supply. In other words, difference was made visible, and was seen as negative. The difference was also always economic, religious, cultural, linguistic, and in the case of the Roma, racial. The ties of kinship came apart – but the question remained, why?

It may be easy to blame it all on the existing enmities between the Serbs and the Croats, and all the others who had fought against each other previously, but there was a parallel truth too – that all these people had managed to co-exist, intermarry and build a functional society for nearly five decades. I myself was born as a result of this unity, between a Serb and a Croat, though I prefer not to think of myself in this way because these categories were not what I was raised with and I do not identify with them.

I think the answer to the ‘why?’ lies in the very make-up of the Yugoslav system, a system that can be clearly paralleled to many other countries in the world today where fascism is on the rise. In Yugoslavia, the Slavs were the superior ethnic group, with the Serbs and Croats taking a firm priority – and this superiority was posited against the Albanians and the Roma – non-Slavic people, who speak non-Slavic languages, and were firmly kept in designated social roles. The Albanians were to be found mainly selling cheap cakes and street snacks, working menial jobs; some were in the jewellery business, if they were wealthier. The Roma took barely any part in the established professional sectors, lived in slums, collected iron and paper, or begged and sold second-hand goods. The Albanians were looked down upon as second-class citizens, and the Roma were racially abused (both these groups are still viewed as inferior and suffer abuse). We had ethnic slurs for both the Albanians and the Roma, which were, and still are, used in everyday speech in reference to them and in order to insult someone we might see as having the characteristics of these ethnic groups.

Yugoslavia’s very name means that it is a land of the ‘Southern Slavs’ (Yugo-refers to ‘jug’, which means south). The supposed inherent superiority of the Slavs – cultural, linguistic, social – enabled the resurgence of Milosevic’s Serb nationalism against the Kosovar Albanians, and unlocked the door to the chaos that swallowed the region, working like a domino effect of death, setting off the Croats’ own supremacy against the Serbs, the Muslims, and so forth. In other words, despite our proclamations of unity, ultimately we did not face – and get rid of – the fascist within. The very term ‘ethnic cleansing’, used so often in reference to the war in Yugoslavia, is a fascistic phrase, since the idea of cleansing is in most other contexts used with positive connotations.

*

Ever since I moved to the United Kingdom in 1992 I was told that Yugoslavia had been a totalitarian state, that we had been indoctrinated, brainwashed, unfree, undemocratic. I was told that Britain’s citizens were free of indoctrination, that their brains were unburdened by propaganda, that the British were democratic. But everywhere I looked, I saw class privilege, industrial poverty, racial discrimination, and patriarchy. The only full freedom I perceived, was the freedom to shop, seven days a week. The country that thinks itself the most free in the world, the US, was founded on slavery, one of humanity’s worst crimes, and it was the European colonial powers that made this possible. None of these countries have faced or reformed their social foundations to reflect and right this injustice – if anything, by exporting the West’s version of democracy, which only exists insofar as it is in service to capitalism, the legitimacy of global social injustice was cemented.

Looking at fascism today as it spreads across the world, we see Western nations living in the myth of democracy. The myth of democracy has been exported to the rest of the world as one big advertisement of the desirable Western lifestyle. What this myth omits from reality is that this lifestyle can only be sustained if we ignore its foundations, i.e. the fact that its historical wealth was built on the profits made from feudalism, colonialism and slavery. The Western world was self-destructed in World War Two by the ultimate supremacist desire: to conquer the world and exterminate Europe’s non-whites, the Jews, the Roma and the Slavs, among the many others seen as undesirable. The lessons from World War Two were, as John Berger says in Ways of Seeing ‘cultural lessons half-learnt.’ Capitalism, already inherent in colonialism and therefore in fascism, became the shining beacon of the post-war West, and ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ became its bywords. Both of those ideals – of freedom and democracy, ideals we should indeed pursue – were thus perverted. While I am firmly in favour of the existence of a European Union, one cannot but feel cynicism when thinking of the fact that the countries that are at its founding heart are all colonial powers, and many of their World War Two governments supported and collaborated with Hitler’s Germany. It is unsurprising therefore that fascist ideas were recycled into capitalism’s democratic values and exported to the rest of the world – the ideal of (white, Western) beauty and superiority, competition, and above all, (purchasing) power as the index of human relevance. Beneath all these, white supremacy and sexist patriarchy were alive and well, and are unabashedly embodied today in world leaders such as Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, and Jair Bolsonaro, among others.

*

After the declaration of the end of society and history in the 1980s, when individual power in democracy became emphasised, the ideal lifestyle became defined by one’s endless dissatisfaction with one’s own life – as separate from society – followed by the drive to accumulate more. Again, Berger sums it up by saying: ‘Publicity turns consumption into a substitute for democracy. The choice of what one eats (or wears or drives) takes the place of significant political choice. Publicity helps to mask and compensate for what is undemocratic within society. And it also masks what is happening in the rest of the world.’ In other words, our freedom in the West, especially since the neoliberal wave that has swept the world following the end of the Cold War, only extends insofar as we are free to purchase – we are to follow that one ideal, and never stray from its path.

The democratic Western world was meant to erase its existing and bloody differences, apparently making war a non-option because free trade would remove the need to try to invade and pillage other nations. But the Western world is the industrial world, and depends on the maintenance of dominant global structures of cheap or free natural resources and labour from countries that were previously colonised, all of which translates into the supremacy of the white world. And just like the fascism local to Yugoslavia’s ethnic groups was able to flourish when placed against the non-Slavic (less human, poorer) Other, the West’s fascist resurgence has been made possible with the introduction of the poor non-white migrant who threatens to shatter its democratic myth by landing on its shores. One must not forget the speed with which money was raised for the reparation of Notre Dame, while ‘compassion fatigue’ set into the European consciousness at the sight of so many drowning migrants who are expelled from their own lives by the poverty and war wrought on by European colonialism.

Compassion, the core value of Christianity, the religion that informs the moral norms of the Western world, repeatedly shows up as relative, conditional – and thus inauthentic. In the place of religion, in atheist Yugoslavia, we had the cult of Tito, who shone as the beacon of all that was considered compassionate and just. But our sense of compassion and justice, if it is to be true, must come from within – it cannot be guided by an external authority – and crucially, it must be practiced without discrimination.

*

It can be said that that the ideal of Yugoslavia was a myth because Tito was a myth – a mythical Father who ‘lead’ the nation the way a parent might lead a child. Our moral compass was calibrated by his, our desires directed by him. Ultimately, Yugoslavia fell apart because we did not face and correct the way we saw each other; we were meant to be equal, united, kin – but not if your community was poorer than mine, if you spoke a language that did not resemble mine, if your customs were different than mine, if your skin was darker. All dominant, hierarchical, supremacist systems depend on their survival by pitting themselves against a threatening Other, and then by subjugating them, in the name of some kind of ideal. The Western world is facing its fascist crisis again precisely because it has never dismantled the illusion that it lives in a democracy.

It is not an indulgence of the left to imagine what social order might look like in ten, twenty years across the globe, or to think that humanity needs to do better, that it needs to face its prejudices, its divisions, its myths, its exploitations of the other, in order to improve. This is a matter of urgency, for all of humanity. James Baldwin said that it is not too much to wish to become a truly moral human being, ‘and let us not ask whether or not this is possible; I think we must believe that it is possible’. But we must first reconsider our social and moral myths, and we must look past official history books.

History, in its wider, official sense, as a political narrative that serves as each country’s propaganda, is always, to a large extent, a lie – the UK teaches about slavery from the point of view of abolition, rather than of the monstrous crimes of colonisation and mass murder of the millions of captured Africans, on which Britain’s wealth, class privilege, politics and the very foundations of capitalism, were built and still stand. It is immensely important to recognise how we are taught, and view, our past – as a nation, a continent, a people – in order to justify the crimes of our nation, our continent, our people. We must look at how we justify wealth and poverty, historic oppression and exploitation. We must find ways to see the other as an equal.

And how do we do this? It is crucial to face our own prejudices, myths and ultimately, our own inner fascism. We must understand the damage it does to the other, and therefore to ourselves. It is not ‘human nature’ for the fittest to survive, to accumulate, to deceive, to be cruel and murderous, as we are lead to believe when capitalism is presented to us as the only viable option – it is a part of ourselves that we must face and examine and get rid of, individually and societally. We must look at examples in history where people have come together to help each other, to build for the improvement of all, where we have fought together for the rights of others through love and compassion. Love and compassion are also inherent in human beings. The future of the world is, and always has been, in our hands. James Baldwin said it in 1963, and I shall conclude by repeating his words, searingly relevant as they still are: ‘If we – and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others – do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfilment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!’

Photograph © Alise Sabanova

The post The Fascist Within appeared first on Granta.