In the evenings, at night, there were long, drunken, anonymous parties where Paul lost his friends in the crowd, intentionally lost them, because everybody swooned over him with his swimmer’s torso and his long lashes. Nights when people handed him glasses full of clear or cloudy liquids that sometimes plunged him into extraordinary slowness where everything flowed as if underwater and where gestures were never quite completed, where they barely got nine-tenths of the way through. Nights on rooftops or in basements or at mansions or in abandoned metro stations. Nights full of smoke. Nights when he lost sight of his friends then found them again, but sometimes it wasn’t them, sometimes it was just his face, just his own reflection caught here or there. Nights when people tried in vain to get him into bed. Nights when he was obsessed with sex because at that time Paul was under a curse or a spell, he just couldn’t get rid of his virginity, every time, the girl disappeared or he left or someone showed up or they had to go; but stranger still, even when he had sex, and whatever the definition one gave the act, whether it was ordinary or pornographic or legal or none of the above, even when he inserted his genitals into someone else’s, even when he came with an uncontrollable shudder and the deed had finally been done, he thought, finally! – the next day or a few days later, it was as if nothing had happened. He was a virgin again, and resigned to it. It was a nightmare for him.

He slept little but slept well. Wherever he was, at the university or at the café, in an unknown house or at home, most of the time, just a few feet away would be a screen with flickering images of murders and investigations or funerals and tears or collapses and escapes or questions and answers, or only questions. And he, impervious to all these tragedies, slept peacefully. But that was before Amelia Dehr. That was before the hotel.

There wasn’t much money. His father had been blunt: the classes were fine, the rest wasn’t. He took the first job that came his way, distractedly, without even realising what he was agreeing to; indifferent or inattentive, because what he cared about was beginning a new life. Security monitoring – or rather, simply monitoring – during the off-hours at the hotel. In the evening; at night. He got bored there. And he offset that boredom by watching the women. Watching them at a remove. He looked for them. Sometimes he found them, sometimes he lost them. In any case, it was a game he played without any of them knowing. This one leaving her room and immediately disappearing, vanishing. Only to reappear, somewhere he hadn’t expected, as if by magic, slipping from one small window to another, almost at random. There were nine cameras and just as many squares on the monitoring screen, Paul’s screen. He waited for surprises; he could only anticipate their trajectories to a certain degree, because that didn’t account for random stops, sudden about-faces. He stared at all those bodies walking around and thinking thoughts he couldn’t see on the screens. He couldn’t see what had been forgotten in the rooms, on the nightstands, in the bathrooms; and he had no hope of seeing any lingering afterthoughts. And every so often came one of Paul’s favourite moments: rare, unexpected, evasive embraces in the emergency stairwells. All he ever saw was a fire door slowly – lazily – closing. He couldn’t really say that he enjoyed his job, which he didn’t think of as a job so much as an accident – less than that in fact, an incident, nothing more: a casual thing. But he could say that he enjoyed watching women. That he enjoyed looking down at them, playing at (or so he told himself ) looking down on them – and only at the hotel, only at night, was that possible for him, specifically because of the cameras, aimed so sharply downward that he was positioned high up, like the sun, like some god. If the warmer air – the sighs they exhaled as they redid their make-up in the elevator’s infinite mirrors, the seismic heat their warm flesh exuded as they stood in these empty, thoroughly ventilated spaces – and these exhalations rising up, accumulating beneath the ceiling, could see, then that vapour’s gaze would be the gaze Paul now had. So dreamed Paul.

When the women weren’t going in and out much any more or he wasn’t watching them much any more, he tried to study. He liked university but more than that he liked being a student, it exhilarated him, as did the pride his father felt – which didn’t keep him from being, deep down, a bit jealous of Paul, just a bit, in those little crannies of his heart of which he himself was unaware – actively, insistently unaware, in total denial. He would rather cut off his arm than admit it, because he was a good man, as proud of his goodwill as he was of his son, and a good man doesn’t envy his only child. But, at the construction site, he sometimes thought of that university and spat in the drywall, and sometimes pissed in the drywall, as people have always done – general hygiene notwithstanding – to bind the components, to (this Paul knew, even if his father didn’t) alter the pH, the acidity, the stability; and to (this his father knew, even if Paul didn’t) leave something of oneself in someone else’s space, in walls that construction workers laboured to build with no hope of ever living there. To secretly, silently spit or piss on other people’s comfort.

Their origins were modest and they took nothing for granted, especially not university education; they lived, had lived, Paul thought, as if nothing under their feet was certain. As if they were on water – but that image didn’t occur to him then; he would only think it much later, after finally meeting Amelia Dehr.

He tried to study but needed to take in far more than just his architecture classes, which sectioned off various eras, areas, and approaches. He had cut off – or so he thought – all contact with his past, which he didn’t think of as a past so much as an incident, more than that, an accident. The first eighteen years of his life had given him a particular body, and this body had a particular relationship with space, with others. He sensed that he didn’t quite belong. At the outset, he had observed. And imitated. First the clothes, which he stole. Then the haircut, which he’d had to adopt a whole new language just to describe, to ask for. It was a challenge he had never faced before, as complex as an international expedition, the greatest of conquests. Finally, he mastered the delicate art of talking. But this drained him. Some nights in the dorms he stayed in his bedroom, in the dark. Listening to the noises in the hallway, and all the other students’ chatter made him seasick; and if someone knocked on his door, he wouldn’t answer, the idea that it might be a mistake horrifying him just as much as the idea that it might not. He was terrified that it would never end and, even though it never did quite fade away, not really, still it only lasted two weeks, maybe three, and then it didn’t matter any more. He was already feeling at home, or so he thought. He had closer friends than ever, whom he loved intensely, for whom he sometimes thought he would have given an arm, a kidney, even. But sometimes he forgot their names. Or their faces. At three or four in the morning he would realise that all he retained of this friend, this guy or girl, was just a blurry shape. And sometimes it was just his face, just his own reflection caught here or there. Maybe deep down some part of him still lived in darkness. And maybe, worse still, he had gone on to think of this darkness, in bleak terms – all the bleaker given that he was an eighteen-year-old man with a swimmer’s torso, with long lashes, who now had a new self – as real life.

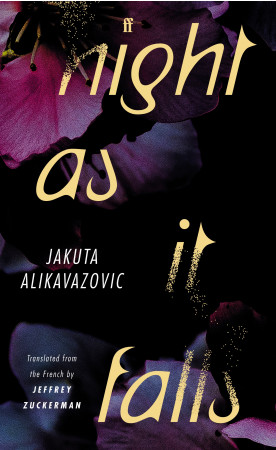

Image © Rookuzz

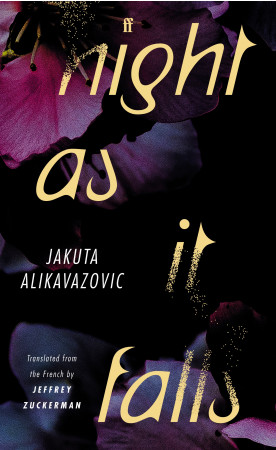

This is an extract from Night as It Falls, out now with Faber.

The post Night as It Falls appeared first on Granta.