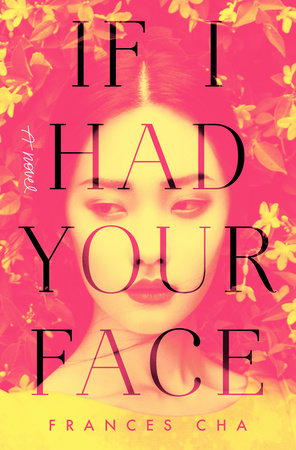

In Frances Cha’s debut If I Had Your Face, four women reckon with their past and present circumstances as they make their way through the wilds of contemporary Seoul.

The beautiful, icy Kyuri works at a room salon pouring drinks for wealthy men. Miho, an artist who won a scholarship to New York and uneasy entry into the city’s upper echelons, is dating the heir of one of the country’s major conglomerates. Ara, who can’t speak, works in a hair salon and worships a K-pop star. Wonna is pregnant and wonders how she and her husband will afford to raise a child. Sujin has plastic surgery done for the chance of getting herself on the path to a better job.

Cha, a former travel and culture editor for CNN in Seoul, offers a crisp portrait of the South Korean capital and its various obsessions—plastic surgery, class, food, and skincare—through the alternating voices of the four women. I spoke to Cha, who lives in Brooklyn, about judging plastic surgery, K-pop fandom, and Korean fried chicken.

JR Ramakrishnan: One of the fixations of your novel is beauty and Kyuri is the plastic surgery enthusiast. From the outside, it seems to be a very harsh obsession and one that comes with a lot of pressure and debt. Would you talk about this culture of plastic surgery?

Frances Cha: Kyuri represents the most extreme of that kind of mentality towards plastic surgery. I think it’s really a cultural difference in the way that things are more blunt in Korean culture. Whenever the subject comes up, I do feel that there is a judgment about plastic surgery. It’s very real and I completely understand where it comes from. There is this sense that you should never have to change who you are. That to change means that you are bending to societal oppression and is considered frivolous and weak.

However, something like braces, which is very prevalent in American society as well, has a similar effect to plastic surgery. It costs a lot of money, takes a lot of time, involves pain, and it drastically changes your face. You don’t really include that in the same category as plastic surgery and it probably is, in ways that your confidence is affected and how that, in turn, affects all parts of your life—from your love life to your job prospects.

Plastic surgery is considered a very tactical way to make your life better. [But] I really hate the fact that it’s generalized for all of Korean society.

So yes, plastic surgery is considered a very tactical way to make your life better. I really hate the fact that it’s generalized for all of Korean society. I know Koreans who have had plastic surgery and I know those who haven’t and would never. I really don’t like the generalization that all Korean women have had it, but I also don’t like the judgment of anyone who’s had it.

The women in my book are not born into wealth and status. Even if they did have academic success and got a job with a really good salary, oftentimes, it’s impossible to buy an apartment because real estate prices have skyrocketed so exorbitantly. You need help in some form, whether it’s from your family, or you get a loan. But again, loans require financial standing and all of that. And so, the very practical way for Kyuri and for Sujin to make their lives better is by getting plastic surgery and having that improve their job prospects. I would hope that the reader will reserve judgment on them. I wanted to explore the deeper reasons why they make the choices they do. These are not, to me, frivolous or vain choices.

JRR: Status is everything, it seems. We see Miho navigating the upper-class world of Ruby and Hanbin both in New York and Seoul. In Kyuri’s world—she is the top girl in her room salon and had to work her way up there. You write (from the realist Kyuri’s perspective) “It’s basic human nature, this need to look down on someone to feel better about yourself. There’s no point getting upset about it.”

You have also an especially urban marker—the boundaries of what is the city and what is not—when you have one of the Bruce, one of Kyuri clients, make an offhand remark about a place that “barely counts as Seoul.” I also feel like the where-did-you-go-to-school question that Miho fields from Ruby’s rich friend is so loaded, but obviously everyone everywhere asks this in social contexts. Is it especially next-level in Seoul? Could you discuss this?

FC: Yes, the part about Miho being asked about her middle school actually comes from my own experience. I attended a public middle school in a province of Korea. It’s not like it was that far outside of Seoul, probably about an hour and a half from the center of the city. Some of the responses that I would get upon being asked that! Like where?

Korean society is so connected. You are always trying to identify what mutual person you have in common and the easiest way to do that is through finding out which school you went to. I do see, again, from how Western perspectives that this might all be very terrible, but it’s actually stemming from a place of trying to find connection and trying to understand the other person and contextualize the other person. And yes, of course, there’s some judgment embedded in that.

New Yorkers have such disdain for New Jersey, which I find so ridiculous because it is literally 10 minutes away.

But New Yorkers also have these preconceived notions about neighborhoods. Living in the West Village versus, you know, Queens, for example. What kind of connotations does that bring, or, God forbid New Jersey, which is where I am quarantined right now. New Yorkers have such disdain for New Jersey, which I find so ridiculous because it is literally 10 minutes away. I just have a heightened observation of these dynamics because it’s just a very different cultural norm.

JRR: Can we talk about Ara? Her story is intriguing because she can’t speak—because of a childhood incident—and she is obsessed with a K-pop idol in the novel.

FC: My grandmother was deaf from her early 20s. Because of her disability, she very much lived in her own world. I would have all these questions to ask or want to ask her but it was impossible to infiltrate her world, which was very isolated even if she was with other family members. She was an inspiration for Ara.

Also in Korea, I go to the hair salon often because it’s so cheap. A beautiful, amazing blowout is like $10. I have this kind of therapist relationship with my stylist, who I’ve been going to for 20 years. I really believe that hairstylists function as therapists. They definitely do in the West as well but I think it’s more intensified because you don’t have therapy at your disposal in Korea. I’m so grateful to my stylist and was thinking of her a lot.

Ara’s K-pop obsession came from when I was in a very dark place in my personal life after my father passed away. I went really off the deep end into the world of K-pop. The way that Ara is immersed in that world and in that all-consuming fandom is from my personal experience. I wanted to have her to be isolated but at the same time working (at the salon). I love Ara so much. She comes from a very personal place.

JRR: There is a lot of abandonment (by parents, lovers, etc.) but also strong friendship in the novel. Could you meditate on that?

FC: I wanted to explore people who are not born into wealth and who have to carve out a life for themselves and rely on each other. In Korea, friendships are so intense. People really go to bat for each other in a way that is just so moving and dramatic.

I wanted to explore people who are not born into wealth and who have to carve out a life for themselves and rely on each other.

This fierce loyalty often lands people in trouble because of nepotism. In every industry and at every level, there are people who get into trouble because of this. In general, this actually comes from a place of really caring for friends. You feel bad for not helping people out if you have the power to do so. It’s considered a betrayal if you turn your back by not helping someone else if you can.

When I was at school, I used to volunteer at an orphanage, which inspired the one in the book. It was a very formative experience for me, this isolated orphanage in the middle of the woods and seeing the children grow up and build bonds there. In every stage of my own life, I’ve had friends who have pulled me out of dark places. I wanted to explore how even if you are abandoned by your family, it’s possible to have your own family by making one, which is what the women in the book are doing.

JRR: It seems that in the last decade or so, there’s been this growing Korean literary mafia. I don’t know if Alexander Chee and Min Jin Lee are the capos or what, but what an incredible output recent years have brought! What do you think of this flourishing? What are your Korean American and Korean literary favs?

FC: I don’t even know where to start with gratitude and my absolute idolization of the incredible Korean American and Korean writers out there! Janice Lee is amazing. She has also been so incredible in her mentorship and the way that she’s encouraged me in key moments in my career.

I had the honor of being published on the same day in the U.S. as Kim Ji-young and her book, Born in 1982. It came out a few years ago in Korea, and has been a sensation. I think it is an absolutely incredible literary piece. Han Kang, who wrote The Vegetarian, has been incredibly inspirational as well. Baek Hee-na, who just won the biggest prize in children’s literature in the world, is someone I appreciate on a daily basis because I have children.

E.J. Koh’s The Magical Lives of Others is remarkable. I have been recommending it and gifting it to everyone. There’s Ed Park, who was one of my workshop professors at Columbia, just wrote for the New Yorker about the rise of anti-Asian sentiment in the States.

JRR: Korean culture—cinema, skincare, and pop music—has been having a moment globally. What do you think is the greatest Korean contribution to global pop culture thus far? My vote is for the spa culture. I love Spa Castle in Queens. Have you been there?

FC: I have not but I’ve actually covered spa culture a lot for CNN. I interviewed the ladies who scrub in a piece I call the Secrets of the Scrub Mistress. Not pop culture exactly but right now I would say drive-thru coronavirus testing is a life-changing and life-saving modern Korean invention. I would say Korean fried chicken too. I could subsist off that exclusively.

The post 4 Working-Class Women Fight For Success in Hyper-Competitive Seoul appeared first on Electric Literature.

Be First to Comment