1.

The summer of 2016 in Paris was a season of escalating heat, and 19 July was the hottest day so far that year. That afternoon around 5:15 p.m., about thirty kilometers north of the city in a suburb called Beaumont-sur-Oise, as the temperature reached its peak, a team of gendarmes in the Peloton de surveillance et d’intervention (PSIG) responded to a call on their radios in pursuit of ‘un homme musclé de type africain’ who was said to have violently evaded arrest. A brief foot chase ended when a bystander alerted the three policemen that the young man they were after had ducked into a ground floor apartment, where they found him a moment later, hiding facedown beneath a bedsheet in front of the couch. They used their knees to apply the total of their collected weight to his arms, legs and back in order to overpower him as he thrashed beneath them, crying out that he couldn’t breathe. They managed to cuff his hands behind him, and hauled him to his feet. On the frogmarch to a police van nearby, he complained that he was still having trouble breathing, and in the course of a few-minute ride to the gendarmerie across the river in Persan, the officers noted that he had begun to slouch in his seat, his head hanging forward and lolling back and forth. There was a hospital less than five-hundred meters away, but they continued to the station, where they discovered he had lost control of his bladder, and seemed to have blacked out. In the courtyard where they were parked, they laid him out face down on the hot pavement, and at 5:46 p.m. radioed for emergency medical services, who, finding him ‘clearly unconscious’ and unable to detect his pulse, asked the officers to remove the cuffs. The ranking gendarme more than once refused to do so, according to testimony one of the medics gave later, because the officers, who’d made no move to administer first aid, thought he was probably faking, and because he was ‘a very violent person’ who would surely try to escape. For the next hour or more the gendarmes looked on as the medical team administered CPR and defibrillation in an effort to revive the subject. Finally, at 7:05 p.m., the doctor pronounced him dead. This was Adama Traoré, who that same day had turned twenty-four.

*

In part because the French Revolution and the protests of May 1968 loom so large in the national psyche, labor rights take up a lot space in French culture, to an extent that sometimes eclipses other concerns on the political left, such as the need to reckon with the country’s colonial past. Over the past year, the violence with which the French police have met the gilets jaunes protests each Saturday has been widely examined in the press and criticized by the public. Within only a few months, eleven people had died in connection with the protests, and the thousands of recorded injuries included teeth, fingers, hands and eyes lost to rubber bullets, stun grenades, and tear gas canisters. As if it weren’t clear enough, the spirit in which law enforcement wields these and other weapons became shockingly vivid to me at the gilets jaunes’ May Day march last year, when the Compagnies républicaines de sécurité (CRS) set up checkpoints at which they confiscated breathing masks, goggles and other protective equipment. At one such checkpoint, a protester asked an officer, ‘We don’t have the right to protect ourselves?’ The officer responded that it defeated the purpose. What was the purpose, the protester asked. ‘To discipline the people,’ the officer gravely replied. The facts behind this sentiment are catalogued in a sixty-page report compiled by the Observatoire Girondin des Libertés Publiques, which details a return to the aggressive tactics of crowd control employed by the former Peloton des voltigeurs motoportés, a brigade of riot-busting motorcycle police that was dissolved in 1986 after two of its members chased down a twenty-two-year-old student protester, Malik Oussekine, and beat him to death.

The PVM was formed in response to the 1968 student/worker protests, but their brutality and their mechanics are rooted in French colonial rule. During the Algerian War of Independence, Paris police prefect Maurice Papon, in order to stifle support for the Algerian Front de libération nationale (FLN), created auxiliary brigades of police officers, which tortured, held indefinitely in extra-judicial detention centers, disappeared, and outright murdered Muslim workers they rounded up in regular raids on tenement hotels and shanty towns. This reign of terror reached its peak on 17 October 1961, when Papon gave orders to attack a peaceful march in Paris. ‘You will be covered, I give you my word,’ Papon told his officers. ‘When you inform headquarters that a North African has been killed, the ranking officer at the scene will have everything necessary so that the North African had a weapon on him.’ During the onslaught of unchecked police violence surrounding this attack, as many as three hundred protesters were killed. Many were shot or beaten to death; others, such as fifteen-year-old Fatima Bedar, were simply hog-tied and dumped into the Seine to drown.

Repression, forced relocation, surveillance, reprisal, intimidation and slaughter were skills Papon picked up as a secretary-general in the Vichy regime, where he directly oversaw ‘Jewish affairs’ in the Bordeaux region (for his role in the deportations he was finally convicted of crimes against humanity in 1998). But they were also time-worn pages in a nineteenth century colonial playbook that Alexis de Tocqueville, as a member of French parliament and later as Minister of Foreign Affairs, enthusiastically championed in the name of spreading liberal ideals and preserving French glory. Before adapting it for use as a police prefect in the fifties and sixties, Papon became intimately acquainted with this playbook as deputy-director of Algeria, a role he assumed in October 1945, just months after the infamous VE-Day massacre at Setif, Guelma and Kherrata, during which the French military killed as many as thirty thousand Algerians in retaliation for a spontaneous revolt that broke out when a soldier shot and killed a young farmhand named Bouzid Saâl for the offense of waving an Algerian flag.

Since 1978, it has been illegal in France to collect data related to race and ethnicity, a policy designed to expiate the sins of the Occupation government in which Papon was so instrumental, but which has instead provided Papon’s successors in policy and law enforcement a curtain behind which to enact their most racist instincts. Even in the absence of such data, reports by organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the French government’s own Défenseur des droits make it plain that for black and Arab residents of French banlieues like the one where Adama Traoré was killed, whose communities have been victims of globalization and de-industrialization for as long as anyone in France, state violence has always been a fulcrum upon which the double-bind of their existence turned: on the one hand, as an instrument of systematic exclusion from Frenchness, and on the other as punishment for not being French enough. It’s laughable to suggest France’s present approach to policing is only a response to the violence and destruction wrought by the gilets jaunes; Papon is long dead, but his legacy has persisted unrelentingly in the culture of law enforcement divisions, like the PSIG, assigned to minority and immigrant populations. ‘We don’t have to demonstrate in the streets to get killed,’ Adama’s sister, Assa Traoré, told me when I visited her at home this fall. ‘Our neighborhoods are their training camps, they practice on human flesh.’

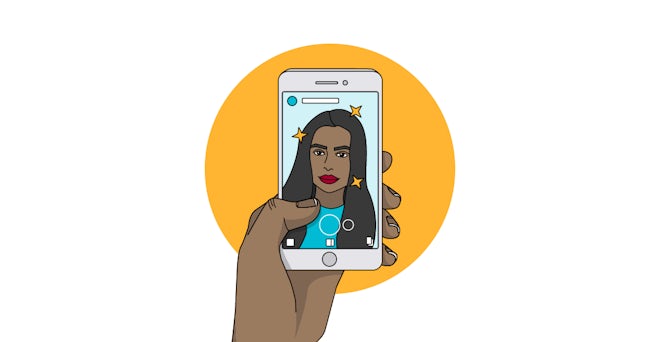

Assa is the spokesperson of the Comité Vérité et Justice pour Adama, the public face of a protest movement whose original goal was holding the police to account for Adama’s death. Over the past three years, it has become a rallying point in a larger movement for social and racial justice in France. ‘With my brother’s [court] case,’ she said on the public radio station France Culture earlier this year, ‘we’re going to change things for all the Adama Traorés.’ Her level, penetrating gaze, and the long hair she wears variously in tight braids or a formidable afro, have made her irresistible to photographers. If the French media’s interest in her has at times felt superficial, she’s nevertheless managed to make her mark on public discourse by the force of her own will and intellect. On TV and the radio, in the pages of magazines or standing in front of crowds, she expresses herself in paragraph form, with searing moral clarity and in a steady voice that sometimes quakes ever so slightly with sorrow and anger. Meanwhile, the two books she’s written – Lettre à Adama in 2017, and Combat Adama in 2019 – have inscribed her family’s experience indelibly into a national narrative of systemic racism and injustice, and have solidified her role as a national civil rights leader. When I first met her, this summer, it was at a reading from the second of these books in the Paris suburb of Montreuil, to which she arrived two hours late. Taking her seat at the head of the room, she excused herself in only the most perfunctory manner for the delay, another quality that makes her such an effective spokesperson for a cause that’s often relegated to the margins of French culture: her refusal to apologize for the space she’s claimed in public life. If the press has learned to cover her cause to her satisfaction, she told me, it’s because she hasn’t given them a choice. ‘It’s because we’ve made them,’ she told me.

In Assa’s view, deaths like her brother’s form part of a post-colonial history whose human toll is invisible to much of France. ‘The story of Adama Traoré,’ she insisted, ‘doesn’t begin on 19 July 2016,’ or even ‘on 19 July 1992 in that hospital in Paris with his twin sister’. It begins in 1964 with her father, Mara-Siré Traoré, packing a small backpack and, against his own father’s wishes, slipping out of his house in the dead of night at seventeen years old. He crossed the border out of Mali and found his way from one country to the next, across the Mediterranean until finally he arrived in France, where he married two white French women before meeting Assa’s mother, Hatouma, and later, Adama’s mother, Oumou. ‘We can’t talk about our struggle without talking about our parents,’ Assa told me. As the spokesperson and figurehead of a movement that’s been gathering force over the past three years, she’s made it central to her message that the problems of the present start with the very real facts of our forebears’ lives. ‘All of this could be avoided if our parents were given an integral place in society,’ she said. ‘If they were taken into consideration, granted importance.’

It’s an importance they earned, as she sees it. Like half a million other men from North and sub-Saharan Africa, her grandfathers fought for France in the Second World War: one gave his leg; the other his life. Her father arrived during ‘Les Trente Glorieuses,’ the thirty years of economic expansion that followed the war, thanks in no small part to an immigration policy designed, in the face of a severe labor shortage, to attract temporary workers from Africa to rebuild the country on the cheap. It was as a construction worker that Mara-Siré found work when he arrived in the south of France, and it was as construction worker that he became a tireless provider for his seventeen children and their four mothers, eventually earning a post as foreman in Beaumont, where he moved with his family in 1988. Like millions of other immigrants in the twentieth century, Mara-Siré stitched himself into the fabric of French society, only to find himself confined by a racial and cultural divide that remains in place to this day.

‘We grew up all together,’ Assa told me. ‘My father worked hard to make sure we weren’t a broken family, even with all the separations.’ Mara-Siré was strict, Adama’s mother, Oumou, told me, but he had a warm laugh. He took enormous pride in the family he’d built, and the life he’d given them. He gathered them around and told them stories of his life in Mali, the misadventures of his early days in France. He kept the house full of food, and anyone who stopped by was offered something to eat. He placed an enormous value on education, and made sure his children had time and space to do their homework. With him at the head of the family, the Traorés lived in a kind of bubble, Assa told me, where the danger and the ugliness of the outside world didn’t reach. ‘That’s how we grew up,’ she said. ‘My father kept his family close, […] and he took care of us all.’

All that changed when, after a lifetime of breathing asbestos in the name of reconstructing France, Mara-Siré died of lung cancer – another Traoré who gave his life to the nation, Assa would later write: each as if ‘to help build a system that would kill a Traoré in the generation that followed.’ In order to make ends meet, Hatouma and Oumou found work as cleaning ladies, working twelve hours or more per day. Assa, who had assumed the role of caretaker during her father’s illness, was fifteen at that time, and now found herself playing the part of mother to her younger siblings. ‘I was the one who went to parent teacher conferences,’ she told me. ‘I was the one who went to pick them up from the station when they were detained.’ In a system that criminalizes the very existence of black boys, that turns its back on them in schools, and that passes them over for all but the most menial jobs, she said, losing their father was like ‘being cast out the door into a great void, in which they had to find their own way.’

*

‘I think honestly a big part of life for young men in these neighborhoods,’ the co-author of Assa’s second book, Geoffroy de Lagasnerie, told me recently, ‘is a complete estrangement from what we call the general politic.’ On consecutive days, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were killed by the police in the United States. In the north of Paris, migrants and asylum seekers kept arriving in far greater numbers than the government was prepared to accommodate, and residents of the neighborhoods where they’d made sprawling camps were getting steamed. In a preview of the gilets jaunes movement, proposed changes to the labor law had resulted in enormous marches, widespread vandalism, violent clashes with riot police, and an Occupy-style encampment in Place de la République. Ever since the attacks in November, 2015, the city had been palpably on edge: on every face you passed in the streets could be read paranoia and distrust, and any public commotion caused a moment of sincere alarm. In June, thousands upon thousands of football fans descended on the city for the Euro Final, spilling out of bars and shambling through the streets and brawling on the train, and gathering nightly not only in stadiums but in a great, seething mass on the Champs de Mars. The Parisian bourgeoisie, consumed by the unfamiliar pressures of anger and fear, had reached an unspoken consensus that the city would surely be targeted once again, and when the tournament ended without incident, the entire nation had barely heaved a sigh of relief before, on Bastille Day, eighty-six people were killed during an attack in Nice. The military doubled down on Opération Sentinelle, a ceaseless patrol of the nation’s streets, and dozens of personnel vans, packed with clean-shaven, fully armored forces de l’ordre, lined Place de la Concorde and the rue du Rivoli. ‘Fear suits the government very well,’ Assa told me. In the days and weeks and months that followed, the idea became ever more deeply entrenched that the state would protect the public from the violence of black and brown men. Very few people were publicly making the case that black and brown men needed protection from the violence of the state.

It was just five days after the attacks in Nice that word spread among members of the Traoré family that Adama had fled the police to evade an identity control – city hall had called that morning for him to pick up his new ID card, but he hadn’t gotten around to it – and had suffered a fainting spell of some kind at the gendarmerie. Around seven, Assa, who was leading a weeklong excursion to Croatia with a group of students, heard that he was in the hospital. Her mother and her brother Samba went to the hospital in Beaumont, but were told he wasn’t there. They called around to every other hospital in the area and each time were told the same. Among the rest of the family, ‘fainting spell’ had become ‘heart attack’. Meanwhile, at the hotel in Rabac on the Mediterranean coast, Assa kept herself apprised, trying to fight back a sense of panic that was rising in her chest. ‘I was saying to myself, how is it that, “he had a fainting spell, he’s in the hospital”,’ she told me. He was just twenty-four, and he was in perfect health.

She’d been to Beaumont just two days before she left. ‘I saw all of my brothers except Adama,’ she said. She’d ordered a birthday gift for him, a djellaba in black and gold, and she called to let him know it would be arriving in the next few days. He offered to come back to see her before she went abroad, but she said not to bother – she just wanted to send a kiss, she would see him when she got back. She remembers hanging up the phone, ‘and as I’m leaving […] I see the gendarmes coming, and I call my mother and say, “tell Samba to call the boys inside, the police are coming that way.” […] As soon as we see them we know we’re not safe.’

When Assa heard that Adama was in police custody rather than in the hospital, she was relieved. He’d been arrested before, and it wasn’t ideal, but, unlike a sudden mysterious health crisis – the term heart attack had reached her by then – it was a known quantity, something he could handle. For her brothers, like black and Arab boys in banlieues all over France, Assa told me, getting hauled into the police station was a routine established very early in life. Samba had called the fire department, and they’d patched him through to the gendarmerie. Assa’s mother called Adama’s mother, Oumou, and told her to go by the station. ‘Something strange is happening,’ she told her.

Oumou and her son Yacouba arrived at the gendarmerie around eight-thirty. They rang the bell and asked the duty officer over the intercom if they had Adama in custody. He let them wait while he went to check: after five minutes or so, he came back and said that yes, they had Adama inside, but it was too late for her to see him. ‘I asked if they had contacted his lawyer,’ Oumou told CNews the following day, ‘and he said, “Yes, we contacted everyone, if he asked, we contacted them.”’ But the rumor that Adama had suffered a heart attack persisted, so a little while later, around nine, Oumou rang the bell again. The duty officer reproached her for ringing so late. ‘I said, let me tell you something,’ Oumou recalled: ‘If my son dies, I’m going to file a complaint against you.’ The duty officer assured her that Adama was okay; and when, dinnertime having come and gone, another of Assa’s brothers, Cheikné, rang with a bag of sandwiches for Adama forty minutes later, the officer promised to pass it along. (The gendarmerie in Persan declined a request for an interview, referring me to the gendarmerie in Pontoise, who also declined a request for an interview, referring me to the Tribunal de grande instance in Pontoise, who also declined.)

In Croatia, Assa had just gotten out of the shower, sometime after eleven, when she got a call from her sister Baï. ‘As soon as I heard the way she was crying, I knew,’ she told me. For some time, as Oumou and her family tried to get accurate information, a crowd had been gathering outside the gendarmerie in Persan. Eventually, Yacouba had caught site of an officer and rang the bell; when the officer answered, Yacouba got his foot in the door, and demanded to see his brother. The officer asked for Adama’s mother, and let Yacouba and Oumou inside, where a female officer greeted Oumou, while the captain of the gendarmerie took Yacouba aside, saying that he had information he would share only if Yacouba promised not to make a scene. Yacouba agreed not to react badly, Oumou recounted the next day, and that was when they learned that Adama had been dead for more than four hours.

‘That’s when the war began,’ Assa told me.

With the crowd growing outside and the Traoré family demanding answers, France’s long history of urban revolts loomed large inside the minds of the gendarmes. In an internal inquiry of the Inspection générale de la gendarmerie nationale (IGGN) two weeks after the fact, the committee asked one of the pompiers who treated Adama if he’d like to add anything to his testimony. ‘I know that the gendarmes,’ he replied, ‘before they informed the family, said they had to call for reinforcements, because everything was about to go sideways.’ The crowd had been watching the personnel vans arrive with flashing lights. By the time the gendarmerie finally delivered the news, one hundred and thirty members of the forces de l’ordre had assembled at the scene.

Upon receiving word of her son’s death, Oumou began to wail. Yacouba cried out in anger. ‘I was in shock,’ he would recount in court nearly two years later. ‘I just remember throwing myself at him.’ Several gendarmes who were standing by ready to intervene testified that Yacouba grabbed the captain by the throat and dragged him to the ground. Within seconds they had immobilized Yacouba, sprayed tear gas in both his and Oumou’s faces, and put them out the door.

When Oumou had recovered from the tear gas, she rang the bell again, and the gendarmes said they’d let her in if she came alone. They explained that they’d been looking for Adama’s brother, Bagui, for questioning in connection with an extortion case, and that Adama, when he’d seen them, had fled. Oumou remembered telling Adama that Beaumont city hall had called that morning to say his new ID card was ready; that afternoon, when he crossed paths with the police, he hadn’t yet picked it up. In the van following the chase and his arrest, the gendarmes told Oumou, Adama had suffered a heart attack, which, together with the heat, could be explained by the presence of alcohol, marijuana and other narcotics that had been detected in his blood. She would later learn from another official that no test results had been available at that time. The effort to convince the world that Adama was a criminal, Assa pointed out to me, began with his own mother.

Having communicated this information, the gendarmes tried once again to show Oumou the door, asking her to calm the crowd. ‘They’re idiots,’ Oumou told me. ‘It’s not for me to calm that crowd, they’re the ones who got those people mad.’ When she refused to leave until she’d seen her son’s body, they brought the medical examiner to see her, who was still wearing her blue gloves. The examiner explained that Oumou couldn’t see Adama; he had bled from the mouth and nose, and a mother shouldn’t see her son in such a state. ‘I said to myself,’ Oumou recounted on CNews the next day, ‘if my son had a heart attack, he’s not going to bleed from his nose and mouth.’ She threw herself on the ground and wept. ‘It was God who gave him to me,’ she said, ‘and it was God who took him.’ Then she corrected herself: ‘But it wasn’t God who took him, it was the gendarmes who killed my son.’

The crowd outside the gendarmerie in Persan began revolting the minute Oumou and Yacouba were informed of Adama’s death, setting fires, launching firebombs, and confronting the forces de l’ordre who closed ranks to chase them back to the Boyenval neighborhood in Beaumont. As word of Adama’s death spread in neighborhoods all over Persan, Beaumont and Champagne, Adama’s friends and neighbors – who, as Assa puts it in Lettre à Adama, heard in his death ‘an echo of their own fear’ – took to the streets to riot. On Twitter, witnesses reported hearing gunshots and explosions. Boyenval was cordoned off, but by morning more than thirty cars had been set on fire, along with a nursery school and a municipal police station, and six law enforcement officers had been lightly wounded by pellet guns.

‘A movement without revolts, the media doesn’t show up, the impact isn’t the same,’ Assa told me. ‘With no revolts, there’s no movement at all.’

2.

On the night of 8 July 1981, a group of teens in the suburb of Lyon stole a car, took it joyriding, and set it on fire. Their example set history in motion. The months that followed came to be known in France as l’Été chaud – the hot summer – during which teenage boys from the predominantly North African housing estate les Minguettes ventured repeatedly into wealthier areas of Lyon and stole over two hundred and fifty cars, which they took for joyrides back to their own neighborhood, baiting the police into high speed chases before setting the cars on fire and fleeing on foot. Upsets like this were not unheard of in French banlieues; indeed, they had precedent in the shanty towns over which French banlieues were built, where during the Algerian War, activists and laborers took violently to the streets in support of Algerian independence. But the Minguettes disturbances distinguished themselves by introducing the burning of cars and public property to well-established tactics of smashing glass, looting shops and confronting the police. They also received far more attention from the media. Groups of young men were interviewed for nightly news broadcasts, and explained how they felt abandoned by the state to a future from which there was no escape. According to one broadcast, just four teachers served a population of ten thousand people between the ages of ten and nineteen. Garbage was left in the street, damage to buildings was left unrepaired, and immigrants and their children found it impossible to find a job. ‘We just want the opportunity to express ourselves,’ said one young man. ‘We want people to hear what we’re feeling […] after that, I’m certain they’ll understand, and that they’ll change.’

The Minguettes uprisings distinguished themselves in this way, as well: people did listen, and did change. President Francois Mitterand had taken office just a few months before, and his interior ministry, as part of a top-down political mobilization without precedent in France, commissioned a hundred-page report that called for a complete overhaul of the government’s approach to its immigrant and minority populations. The report emphasized, among other things, the necessity of correcting the misperceptions that shaped institutional and public conversations surrounding these populations: ‘Institutions must accept the working-class reality of these neighborhoods,’ the report asserts, calling ‘for every fraction of the population to be given the ability to express their own identity.’

In addition to heavy investments in education and employment policy, the government launched a series of social programs designed to meaningfully engage inner-city youths, building high quality recreational facilities, funding afterschool programs in sports and the arts and offering fully-funded youth vacations to other parts of France. It did all this according to a principle of decentralization, giving local governments the leeway to engage their communities as dictated by conditions on the ground. These so-called ‘anti-hot-summer’ measures actually worked for a good long while; the eighties saw no further ‘crises des banlieues’. When, in 1983, a police officer in les Minguettes shot and badly wounded an anti-racism activist named Toumi Djaidja, the result was not a violent uprising but rather a protest march, La marche pour l’égalité (or the Marche des beurs, as the media termed it, using the slang term for Arabs). The march began with just a handful of protesters in Marseille, but by the time it reached Paris, seven hundred and fifty kilometers away, it had grown to more than one hundred thousand strong.

The Mas du Taureau cité in Vaulx-en-Velin was a poster-child for these reforms: to combat the neighborhood’s reputation for drugs and crime, the government invested $12 million in renewal efforts: fresh paint, a new public library, a day-care center, landscaping, parks and so on. A newly-built, hundred-and-fifty-foot climbing wall had been open for only a week when, in October 1990, twenty-one-year-old Thomas Claudio died in a traffic accident after a police car – according to multiple eyewitnesses – swerved into his lane and knocked him off his motorcycle. In the four days that followed, hundreds of local youths looted stores, launched rocks at the police, and set fire to the local commercial center, in demonstration of a rage that they articulated clearly in interviews with the press: ‘The cause of the explosion wasn’t that someone died in an accident,’ a nineteen year old of Moroccan descent told the New York Times, ‘the reason was we had it up to here with the police.’

This sentiment was borne out by a 1994 Amnesty International report on police use of excessive force, which noted ‘a disturbing number of reports of shootings, killings and allegations of ill-treatment of detainees by law enforcement officers in France,’ that ‘a high proportion of the victims are of non-European ethnic origin, mostly from the Maghreb countries, the Middle East and Central and West Africa,’ and that ‘alleged physical and sexual abuse was often accompanied by specifically racist insults as well as general verbal abuse.’ Despite the government’s efforts on other fronts, in Mas du Taureax and communities like it all around France, law enforcement maintained a post-colonial attitude of contempt and mistrust toward the populations they were supposed to serve. ‘Peaceful marches aren’t going to accomplish anything,’ a young Vaulais told the eight o’clock news that week. ‘If things blow up, it’ll be heard. If there’s a march – well, silence flies off like the wind.’

Politicians on the left tried to make the case for an expansion of their efforts, but the images of the destruction wrought upon Mas du Taureau seized the country’s imagination. Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Front National took every opportunity to suggest that, as a party leader in Vaulx-en-Velin put it, ‘the solution to immigrants is not integration; it’s sending them back to their country,’ though of course a vast majority of the youth population there had been born in France. Meanwhile, in banlieues around the country, policemen and gendarmes continued to humiliate, harass, brutalize and kill young black and Arab men, more or less with impunity. In the years after Thomas Claudio died in Mas du Taureau, violent encounters with the police led to similar conflagrations at a rate of ten to fifteen per year: in Mantes-la-Jolie in 1991, for example, and in Sartrouville in 1992. In 1993 the National Assembly passed a law limiting access to citizenship for the French-born children of immigrants, and another formalizing law enforcement’s authority to carry out random identity checks of the sort Adama Traoré was fleeing the day he died – measures that raised the harassment and criminalization of minorities to the level of official policy.

As riots became a regular feature of public life, overheated coverage in the French press contributed to a growing national anxiety about crime and lawlessness in areas a lot of viewers would never visit. This same coverage led to a growing consensus that it was the ‘visible minorities’ own failure to assimilate that made their life so hard. With each new iteration of the Mas du Taureau model of revolt, the prolonged conservative backlash to Mitterand’s reforms spread; in 1995, when Jacques Chirac’s conservative government took power and the anti-hot-summer programs, already in decay, were replaced by a law-and-order ethic whose primary target was juvenile delinquency in the banlieues.

In the fall of 2005, revolts erupted in 280 communes around the country when two teenagers, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré hid from police in an electrical substation in Clichy-sous-Bois, where they were electrocuted to death. Chirac’s prime minister Nicholas Sarkozy took an uncompromising law-and-order stance – referring to the boys who’d been electrocuted as ‘thugs’ and invoking the specter of Islamist terrorism. He issued an order to deport foreigners who took part in the violence – a performance for which he was rewarded with an eleven point bump in approval polls that carried him to the Palais Élysées.

3.

Assa Traoré grew up watching these transformations take place around her. She remembers a group of youth leaders from the Protection judiciaire de la jeunesse, a directorate of the Ministry of Justice that was created in 1990 to oversee juvenile criminal law, who gave a presentation in her class when she was ten. ‘When I heard them speak,’ she told me, ‘I said to myself, okay, this is what I want to do. I want to give kids guidance, to help them flourish, give them the freedom to be what they want to be.’ As she got older and continued her studies, it was natural to apply the values her father had instilled in her – the importance of education, a sense of responsibility for the well-being of her family, an ethic of duty and reciprocal care – to the world around her, particularly after her father’s death, when the injustices faced by young people in her community struck her with full force. As an adult, she undertook a sort of anti-hot-summer mission of her own in her role as éducatrice specializée – a youth counsellor for at-risk adolescents who experienced life in France in the same way as her brothers.

‘What happened to Adama,’ Geoffroy de Lagasnerie, a sociologist and philosopher who has written several books on criminal justice, said when we met in September, ‘is the result of a process that recurs more than once a month in a very institutionalized and routinized way. Always to the same type of person, always in the same ways.’ Among the sins that the French government declines to catalogue are deaths that result from encounters with police. But in 1993, after a Paris detective shot and killed a handcuffed seventeen-year-old, Makomé M’Bowolé, at point-blank range in an interrogation room, the French historian Maurice Rajsfus created the Observatoire des libertés publiques. Over the course of the next two decades, the organisation compiled exhaustive data on police violence, according to which ten to fifteen people die at the hands of the police per year. It’s a common enough occurrence that when such a death gets covered in national media at all, it tends to rate not much more than a brief summary of the press release government officials provide. This is the status quo in France and long has been – even after the massacre of October 1961, when over 300 protesters were killed, the French press mainly confined itself to parroting the narrative and figures released by the police. ‘It’s always the same thing,’ explained Samia Tabaï, an activist I met at a protest this summer in Boyenval, the neighborhood where the Traoré family had once lived. ‘Journalists might take an interest, but they’re only interested in the police’s side of the story, they don’t interview witnesses, they get the official version and leave it at that.’

Over the years, an informal protocol has developed in response to this apathy in which the first step is to form an action group like the one on which Tabaï serves as communications director. Hers was formed in 2018, when a 26-year old man named Gaye Camara was shot and killed at the wheel of a Volkswagen Polo by police investigating the theft of a Mercedes-Benz. (The police have claimed he was trying to run one of them down; after an investigation, a judge recently dismissed the Camara family’s case.) In part because they take place in the same isolated communities as the deaths themselves, the protests and marches and rallies these committees organize seldom attract much attention, or, worse, attract attention of the wrong sort. Gaye’s brother Amadi Camara told me about a march the Comité Gaye Camara organized in Champs-sur-Marne, ‘The police in our town, when they saw us in our T-shirts, they told us, “Gaye deserved what he got.”’ (The city hall of Champs-sur-Marne did not respond to a request for comment.) This brand of cruelty had a political edge to it, according to Amadi; it was intended to provoke a violent outburst that would justify shutting the march down, and that would undermine the committee’s credibility and public image. The demonstration came off without incident, which is partly why it didn’t attract much attention in the mainstream press. And while it’s true that what the French continue to call riots still often command the news media’s attention for as long as they last, to a greater or lesser degree such uprisings are usually framed as the expression of a rage whose incoherence provides an ex post facto justification for the routine state violence that incites it, rather than – to paraphrase Frantz Fanon – as an intelligible political response to the way public indifference upholds that routine.

It was in this context that Assa left her job in Sarcelles to form the Comité Verité et Justice pour Adama, a group of activists that combines the Traoré family and friends with a group of experienced social justice activists from groups like the Mouvement de l’immigration et des banlieues (MIB). The objective expressed in the committee’s name – achieving truth and justice in the matter of Adama’s death – is a battle fought on three fronts: in the courtroom, in the media and in demonstrations in the streets. But in a broader sense, their work is very much of a piece with the work Assa undertook as an educator: picking up the government’s slack in her community, trying to give children and teens opportunities that her brother didn’t have to create points of contact between their lives and the larger world. To that end, they give local youths a prominent place in their activism, but they also host film screenings, panel discussions, concerts, athletic training and so on. At some of these the police stand watch in body armor, or from inside armored riot trucks. ‘My brother died by physical suffocation,’ she told me, ‘but psychologically, they’re all suffocating in these neighborhoods. […] There’s a pressure that kills them from the inside and it makes it very difficult to advance and to build, you’re being suffocated from every direction, from school, from work, from home.’

The Comité Adama uses the platform they’ve built to bring attention to other incidents of police violence and to show solidarity at other demonstrations or court cases. The Comité Adama has become synonymous with and enlarged a broader movement against these forces of suffocation. ‘It can’t be said,’ Lassana Traoré, Adama’s older brother, told me on the phone, ‘that we, the Traoré family, have achieved all this success. We’ve succeeded in advancing things a bit further. […] If we’ve become a symbol, we owe it to what came before, it’s thanks to them.’ Still, it’s true that anti-racism and anti-police violence movements in the past have often gotten snagged on the fundamental challenge of getting the public to listen, particularly when what they have to say implicates the public in such vivid and ubiquitous injustice.

In this regard – getting people to listen – Assa has been particularly effective. As her family’s spokeswoman, she’s become a familiar public figure, having made countless appearances on radio and TV programs since she first appeared, in 2016, on Quotidien, a nightly news and culture show. She’s been the subject of numerous magazine profiles and interviews. She’s attracted the support of a wide variety of celebrities, such as the rapper and actor Omar Sy, film-maker Ladj Ly, politicians like Jean-Luc Melanchon and the author Edouard Louis.

But in her hotel room in Croatia the night of Adama’s death, all of that was still ahead of her. At that moment, she knew only that she wouldn’t have the luxury of simple grief. Her supervisor at Les Vignes Blanches, the community center in Sarcelles where she worked, immediately booked her a flight back to Paris. Her students, heartbroken when they learned the circumstances of her leaving, wanted to return with her to Paris for support, but she insisted that they stay behind with her colleague: she had fought hard to arrange the trip, and it was exactly the kind of experience of the outside world she wanted them to have. Unable to sleep, she Googled numbers for news outlets such as BFM. ‘I got on the phone,’ she told me. ‘I said to myself, my brother’s death isn’t going to be a news brief […] where everyone moves on to something else.’ She had seen the same happen to other families too many times.

By the time she arrived back at her mother’s, calm had been restored in Beaumont. Assa was herself at loose ends, consumed by grief and rage. Jannier, the district attorney, had communicated exclusively with the Agence France-Presse, a news agency whose primary client is the French government, rather than making a public statement. This left journalists to piece together a narrative of what had happened from partial quotes. Le Parisien reported that a young man, during his arrest for ‘extortion of funds and domestic assault,’ had subsequently suffered a heart attack and been pronounced dead. Le Figaro reported the same. By morning, news outlets citing the same AFP report had clarified that it was the deceased’s brother, ‘a young adult, well-known to the police’ who was wanted for questioning in ‘an extortion case involving numerous people’. The deceased, they said, had ‘come into contact’ with the gendarmes, and had subsequently died of a heart attack. As yet, no one from the prosecutor’s office or Persan city hall had reached out to the Traoré family to let them know when they might see Adama’s body. The press was their first priority. ‘That’s their way of controlling public opinion,’ Assa told me: ‘discredit the family and make the victim out as a criminal. Except with us it was impossible.’

To the Traorés, the official story strained credulity. They knew they had to get their version of events into the record while they still had the media’s attention, but apart from providing journalists with quotes contradicting the official story, Assa wasn’t sure how to proceed. At seven-thirty a.m., the Val-de-l’Oise police prefect, Jean-Yves Latournerie, was scheduled to give a press conference at city hall. A gaggle of reporters were there with cameras and microphones, attracted, as Assa would later write in Lettre à Adama, ‘by the car fires and the smell of trash burnt in the night’. Latournerie didn’t show up; instead, it was a trio of Adama’s friends who spoke to the press. The reporters were less interested in the circumstances of Adama’s death than in the previous night’s violence and destruction. ‘Well what do you expect us to do,’ one of Adama’s friends responded. ‘Uncork a bottle of champagne?’ A few minutes away at the Persan gendarmerie, a handful of the Traoré siblings, along with a small crowd of supporters, staged a sit-in on Avenue Jean-Jaures, demanding to see Adama’s body. A file of dozens of gendarmes emerged from the courtyard armed with riot shields and batons. The protesters formed a solid mass of bodies, and met them with their hands raised above their heads, refusing to back away. Sihame Assbague, a veteran civil rights activist, captured on video the moment a gendarme discharged his tear-gas gun into the center of the crowd.

In the days and weeks to follow, the Traorés interactions with the state became both more discreet and, in a way, more brutal. ‘From the very first night,’ Lassana told me, ‘we were visited by people who had experienced what we were going through.’ Zyed Benna’s older brother was among them. As were Amal Bentousi and Samir Elyes, who had been organizing against police violence for years. These veteran activists presented themselves to the Traorés as guardian angels, providing detailed advice on what to expect and how to proceed. It’s thanks to them that the family got through that first week, Lassana told me. ‘You have to put yourself in that situation,’ he said. ‘You don’t have the capacity to think, you’re crushed by sadness, you can’t sleep, there are riots going on all night, people coming in and out […] You don’t understand what’s happened.’

On each of the following four days, the revolts resumed at nightfall, and clashes with police grew more intense. The Traoré family, with the help of a lawyer the activists had recommended, conducted a battle with the district attorney’s office in the press and behind the scenes. Jannier announced to the AFP that Adama’s autopsy revealed a ‘very serious infection involving the lungs, liver and throat,’ and that no ‘sign of significant violence was found’. That same morning, after finally being admitted to the morgue to see Adama’s body, the Traorés were summoned to the police prefecture in Pontoise. Knowing the Traoré family was Muslim, a representative told the assembled siblings when they arrived that the authorities had arranged with AirFrance for Adama’s body to be transported immediately back to Mali, in order to be interred as soon as possible, in accordance with Islamic tradition. Furthermore, they’d made arrangements for any family member not in possession of a passport to be issued one right away. (In an open letter addressed to the people of Beaumont, Mayor Nathalie Groux claims this offer was extended merely as a courtesy.)

Their guardian angels had prepared them for this: if they accepted possession of Adama’s body, they would in effect be accepting the government’s version of Adama’s death. It was crushing, but they refused, and requested a second autopsy instead. More than three years have passed since that day, and they’re still waiting to learn the truth about what happened.

*

‘Everything he had, he was ready to give away,’ Oumou Traoré said when I asked her about her son. He was shy, but he was the type of person who would cross the street to carry an elderly woman’s groceries back to her apartment. ‘People knew him for that.’ He was a bit of a health nut, and unlike his brothers he didn’t eat candy, but, Oumou told me, he carried candy in his pockets because there were always little kids around and he loved to make them laugh. Yssa, a seventeen-year-old boy I met at a march in Boyenval this summer on the third anniversary of Adama’s death, told me, ‘Everyone knew Adama, he was a role model in the neighborhood.’ He was always surrounded by his friends, Assa said, and he and his brothers were particularly close – they took vacations together, they played football together, they had each other’s backs. ‘He was very calm,’ she repeated, ‘he never wanted to hurt anyone, but he stood up to injustice. He was a fighter, he wanted to defend everyone.’ In Beaumont, there was no shortage of injustice, she said: ‘So, yeah, he got into fights.’

‘But you can see how well loved he was,’ she said. ‘If he wasn’t so well-loved, we’d have never gotten this far.’ She and her family have made it a point to build their movement in Adama’s image, and indeed, they’ve managed to replicate the gentle attentiveness she describes, and a kind of community-minded joie-de-vivre. But they’ve also replicated Adama’s fearlessness and indignation. ‘A lot of families of victims,’ de Lagasnerie told me, ‘at the beginning, they think, if we respect the prosecutor, if we respect the judge, they’re going to treat us fairly.’ Other activists warned the Traorés against this sort of compliance. They’ve countered the official narrative so forcefully in both the press and in the courts that they’ve managed to keep the state on the defensive for the past three years. The sprawling nature of the Traoré family itself, and the strength of their commitment to each other – another value, Assa points out, transmitted to them by their father – has also made them unusually resistant to the power of the state, which in similar cases has been able to count on a family eventually being defeated by the demands and contingencies of their own everyday lives. It’s not only the lack of a public platform or affordable legal advice, but also long hours to work, children to care for, forbidding commutes to the centers of power in which they hope to be heard. But the Traoré family spreads these burdens among themselves. And while the mainstream media coverage of such affairs evolves slowly, with social networks activists have become their own media, bringing their case directly to the public in a way that’s difficult for journalists to ignore. Videos of statements Assa makes at demonstrations or outside courthouses and prisons, for example, are routinely viewed tens and even hundreds of thousands of times. ‘This is a radical change,’ de Lagasnerie told me. ‘I would say it’s the first movement in France that has succeeded in making journalists really doubt the decisions of the justice system and of medical experts.’

‘She’s consolidated so many different struggles,’ Mami, a former colleague of Assa’s from Sarcelles told me this summer. While the movement’s success owes an enormous debt to the example and experience of activists who have stood beside them, social movements in France, de Lagasnerie explained, have in the past tended toward atomization. ‘Assa said right away,’ he told me, ‘in my family there are white people, there are black people, Arabs, Muslims, non-Muslims […] From the beginning she thought of the Comité Adama as a story of France. So it’s a story of whites, of blacks, gay people, straight people, tall people, short people, redheads, non-redheads – and that’s very new in activist discourse in France.’

It’s thanks to these efforts that a clearer narrative of Adama’s death has emerged. A transcript of the call between the doctor on the scene at Adama’s death and the dispatcher who had sent him on the call, as Vigroueux reported in the Nouvel Observateur, revealed that although Adama’s death wasn’t declared until 7:05 p.m., he was already dead when the emergency medical services arrived. What’s more, the exchange suggested that the gendarmes had misled the medical team profoundly about Adama’s condition: they claimed he’d had a three-minute seizure, and that he had needle marks on his arms, neither of which details the gendarmes mention in the testimony they’d later give, and neither of which was mentioned in the autopsies. The autopsies themselves were the subject of what Le Monde called, somewhat generously, ‘selective communication’: unmentioned in any of Jannier’s public statements is the ‘non-specific asphyxic syndrome’ that medical examiners in both cases pointed to as the possible cause of death. Jannier’s statements invoked ‘a serious infection touching several organs,’ ‘lesions consistent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,’ and the conclusion that ‘no trace of violence was found that could be given as a cause of death’. (The Pontoise prosecutor’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Jannier retired at the beginning of this year and could not be reached for comment.) ‘I’ve noted only the salient elements of the different accounts given,’ he told Le Monde at the time.

At the request of the Traorés’ lawyer, the investigation was transferred to the prosecutor’s office in Paris. Jannier, in what many saw as a consequence of his mishandling of the Traoré case, was transferred from Pontoise to the Paris court of appeals. A subsequent medical report, in February 2017, confirmed the Traorés’ suspicion that Adama was not in fact ill at the time of his death. More than a year and a half later, another medical report ordered by a judge in Paris concluded that Adama’s death could in no way be linked to the actions of the gendarmes, and was instead attributable to a combination of a sickle-cell disorder, sarcoidosis and the heat. The following March, still another report, this one conducted by four of the nation’s leading experts in sickle cell and sarcoidosis at Traoré family’s expense, noted that Adama did not suffer from sickle cell disease, but rather was a ‘healthy carrier’ of the sickle cell trait; and it likewise noted that no stage-two sarcoidosis, from which Adama suffered, had ever been recorded as a cause death. ‘Adama Traoré’s death,’ the report read, ‘cannot be attributed to stage two sarcoidosis, the sickle cell trait, or the combination of two.’ The authors, as quoted in Le Monde, excoriate the science upon which the original report was based, and add that ‘it is astonishing that this forensic expertise has not taken particular interest in the concepts of positional asphyxia, which have been described in several studies dealing with deaths occurring during police arrests.’ In April of this year, based on the new report, a judge reopened the investigation into the circumstances of Adama’s death.

In the meantime, the Traorés’ relations with the state have grown more and more fraught. In November 2016, Nathalie Groux, the mayor of Beaumont-sur-Oise, tried to appropriate municipal funds in order to bring a defamation complaint against Assa for remarks she’d made in a TV interview. ‘The mayor has chosen her side,’ Assa had said, ‘and that’s the side of the police, which is to say, the side of police violence.’ (In her open letter, Groux explained, ‘I have faced calumny, insults, lies, that sometimes affect me as well as my family violently […] (when, for example, I’m treated as a ‘racist’ although my children are mixed race.’) Four of the Traoré brothers have been arrested and tried numerous times, including Yacouba, who in 2018 was sentenced to sixty days in prison for assaulting the gendarme who announced his brother’s death, and to three years for setting fire to a city bus. His brothers Bagui and Youssouf were arrested for ‘insults and violence against security forces’ during a protest against the mayor’s defamation case. In that trial, the brothers were convicted on all charges, including an assault charge supported by a single officer’s eyewitness testimony. They were sentenced respectively to eight and three months of incarceration. As I write this, two of them, Bagui and Yacouba remain in prison.

With so many of her brothers in prison, Assa herself has become a target for what the family calls judicial persecution. Results of the new investigation into Adama’s death were supposed to advance this fall, and although in mid-November a judge did finally appoint a new medical panel to conduct an analysis, so far there has been little news.In the month of October, Assa was the subject of four criminal indictments, three of which charge her with defamation for Facebook posts publically naming the gendarmes involved in her brother’s death, and one related to an event that took place in the spring of 2018, for which Assa is alleged to have obtained the wrong permit. None of these charges carry a prison sentence, but the total of the fines she faces is more than fifty thousand euros. (Through their lawyer, Rodolphe Bosselut, the gendarme’s declined to be interviewed for this story. ‘My clients are tired of being so regularly incriminated in public,’ Bosselut told me in a brief phone conversation, ‘while there’s a file open that says the opposite of what Ms Traoré claims.’) At her arraignment at the Tribunal de grand instance de Paris, to which she arrived twenty-five minutes late in a long black coat and Balenciaga sock-shoes, Assa stood with her arms across her chest as the judge read the charges, including the offending portion of a text she’d written under the title ‘J’accuse.’ The trial is set for May 2021, and Assa can’t wait. ‘They’re trying to transform the transgressors into the victims,’ Assa told me. ‘It’s a gift they’ve given us, and it’s magnificent […] We’ve gained even more support. They’ve made our cause even more legitimate.’

This summer, the committee invited the gilets jaunes to march with them in Beaumont to mark the third anniversary of Adama’s death, and as guests, the gilets jaunes were careful not to overstep. An army of Comité Adama volunteers, many of them local youths, donned green Justice Pour Adama T-shirts to handle security and logistics, ensuring that their supporters remained peaceful and didn’t inflict the sort of damage with which the gilets jaunes have become associated. As the march wound through downtown Beaumont, I watched a man in a yellow vest light a road flare and wave it over his head for just a moment, before a pair of teenage committee members made him put it out. A group of casseurs nearby, their faces masked and their hoods pulled low, made an inventory of the blunt instruments and projectiles in their bags. In their final decision not to put them to use, I read an implicit recognition of the committee’s authority, and perhaps an acknowledgement that the price for any violence they committed against state property would be visited upon a community to which they did not themselves belong. ‘For years and years,’ Maxime Nicolle, a gilets jaune figurehead, said from the stage at the end of the march, ‘you’ve been through things we’ve been experiencing for just eight or nine months […] I’m sorry for not having known, sorry for not having listened, sorry for believing what the media said.’

After the march, protesters spread sheets for picnics and uncorked bottles of wine in a field in Boyenval. A long line formed for barbecue. Everywhere you looked there were children – dancing on stage, chasing soccer balls, blowing bubbles that carried off in the wind. It seemed like a long time had passed since a fleet of coach buses destined for the memorial march in Beamont left from three locations in Paris, each to be pulled over by police so that its passengers could be assembled on the side of the road for an identity check of the same sort Adama had fled three years before, in order to avoid spending his birthday in jail. But that was how the march began.

The coaches made it to Beaumont nevertheless. After a torrential ten-minute squall drenched the assembled crowd, I watched Assa find her way to the head of the crowd so that the march could begin, taking care to stop and exchange cheek kisses with the many familiar faces she passed along the way. Riding in the bed of a truck, she led us past the gendarmerie, where she paused, and for a moment she let the boos and taunts of the crowd echo up and down the street. Then at her command the crowd fell silent. ‘This is where my brother drew his last breath,’ she said. ‘They left him there to die, and he died alone, without his family, without us.’

A pair of young women in their early twenties stood riveted in place, nodding gravely. Their names were Elodie and Brave, a hair stylist and a realtor. Later, they would tell me me that Assa’s strength and courage were an inspiration for black women all over France.

‘Today, we’re here,’ Assa said. ‘Together, we’ll turn this system upside down.’

Images © Chris Knapp

The post No Justice, No Peace appeared first on Granta Magazine.